I go out walkin‘ after midnight, out in the moonlight.

There was a time in history when uttering such words in a church would have been more than enough to convict a young woman of witchcraft. Indeed, many „witches“ were convicted for much less. Luckily, this young lady, Annabelle Neilson (1969 – 2018), friend, muse, and unofficial „wife“ to British fashion designer Alexander McQueen (1969 – 2010), was safely tucked under the shallow awning of the 21st century.

In the Whispering Gallery of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, she pleaded with the canon chancellor to allow a second memorial service to be held for McQueen in the church, despite such an honor being reserved almost exclusively for royalty. The first service following McQueen’s sudden and tragic death had been more understated and reserved, bearing little resemblance to his signature runway shows which were equal parts fashion showcase, art installation and experimental theater.

What could Neilson do to be granted this exception? Sing, the chancellor instructed her. So, she sang the only song she claimed to know. American country star Patsy Cline’s Walkin‘ After Midnight. The charm worked, and McQueen, fashion’s “enfant terrible,” who clothed the concept of Cool Britannia, the genius of a generation, got the send-off he deserved.

There was a time in history when uttering such words in a church would have been more than enough to convict a young woman of witchcraft. Indeed, many “witches” were convicted for much less. Luckily, this young lady, Annabelle Neilson (1969 – 2018), friend, muse, and unofficial “wife” to British fashion designer Alexander McQueen (1969 – 2010), was safely tucked under the shallow awning of the 21st century.

Throughout his career, McQueen did his part to honor those whom history or society had given underwhelming due. His legendary fashion shows were memorials of sorts to history, to his heritage, to those who had been lost to time or because they were deemed unpleasant to remember. His graduation collection from Central St. Martins, entitled “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims,” in an eerie but fitting twist, vanished after its debut and has never been seen since. “Widows of Culloden,” his Fall 2006/ Winter 2007 show, McQueen, who was quite proud of his Scottish roots, alluded to the many men who were killed in one of Scotland’s many uprisings against English subjugation. His 2001 Spring/Summer show “Voss,” crescendoed with the reveal of a naked woman in a gas mask, who’d been sitting in a mirrored box in the middle of the stage, a direct reference to the photograph “Sanitarium, New Mexico, 1983” by Joel-Peter Witkin.

By exaggerating what’s uncomfortable to within an inch of camp, he was at times accused of bad taste, exploitation, and, most bafflingly, misogyny. But while acting as a target of such criticism, he allowed ideas and people that were relegated to the sidelines to briefly take center stage. Sarah Burton, McQueen’s former protege who took the label over after his death explained, “He believed fashion was biography.”

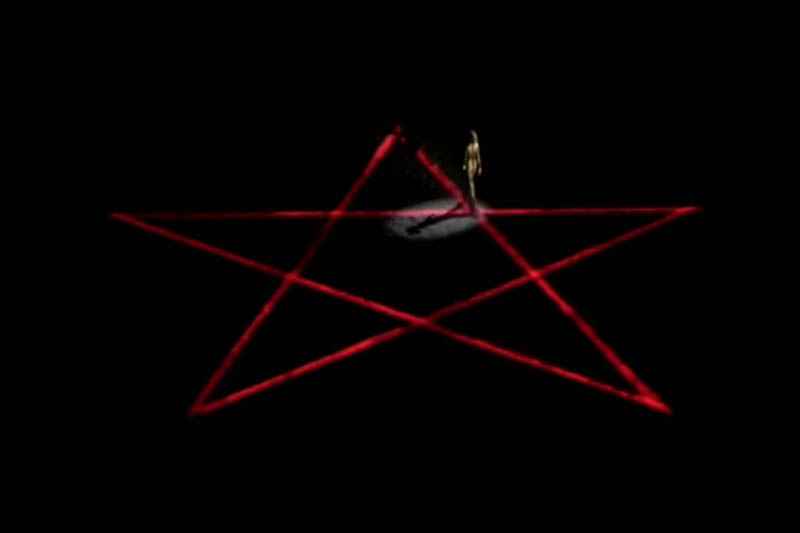

His 2007 ready-to-wear Fall/Winter show, In Memory of Elizabeth How 1692, took its name and inspiration from his distant relative whose own life had been cut tragically short when she and 18 others were wrongfully convicted of witchcraft in the infamous 17th-century trials in Salem, MA. In lieu of a traditional runway, Elizabeth’s models’ steps traced a glowing red pentagram on the floor. The backdrop screen shows three maids wailing, snarling, and chanting incantations. Among the highlights of that collection of neo-gothic gowns is floor-length, black velvet with a capped sleeve bodice of glass beading that, in motion, like flashes of white lightning against a midnight sky.

Black velvet evening dress. In Memory of Elizabeth Howe, 2007. Screenshot

Pentagram Runwway.In Memory of Elizabeth Howe, 2007. Screenshot

Behind glass it stood as the exclamation point of the Major Arcana: Portraits of Witches in America, which recently completed its run at Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum. It’s the lone McQueen dress in the exhibition, despite his being the focus of its marketing campaign. A bit of a glamor one might argue– the museum’s impressive fashion retrospectives, including its still-famous 2016 Shoes: Pleasure and Pain, pack the regional institution with unusual numbers.

The main features of the show are divided between the present and the past; between those who fly the identity of “witch” like a flag, and those whose lives collapsed under the weight of the accusation. On one wall is the reconstructed timeline between Elizabeth How’s accusation and her execution, and letters pleading for anyone to defend her good name. She was lucky in that many neighbors spoke up for her, and her tight knit family made several days-long journeys to visit her in the small, airless room in the Salem jail where the accused were packed together for months.

Lining the wall opposite are portraits of contemporary women who self-identify as witches, taken by photographer Frances F. Denny, who, like McQueen, traced her lineage back to the Salem witch trials, (Denny had ancestors in both the accused and the accuser camps). Closer to tradition are those who describe themselves as healers, a vocation overrepresented among the accused, and those like M. Macha Nightmare, who believe in, and yield, the power of nature. Another subject, Melissa, describes herself as a “kitchen witch,” meaning, apparently, that she rejects the mundanity in life. In general, it seems, the qualifying criteria appears as nebulous as ever.

No interpretation of Salem’s most solemn chapter is more tenuous and flippant than that of present-day Salem itself. The definition of witch threatens to tear as it’s stretched increasingly thin to encompass haunted house tours and occult kitsch. It gets muddled with the increasingly warped representations of Halloween, so that cafes can give themselves a witch moniker as long as they serve pumpkin shaped cookies. Perhaps the most controversial of these dubious connections is the statue of Samantha, the lead character from the mid-20th century American sitcom Bewitched, about a witch living her life as a contemporary housewife. Recently, the statue was sprayed with blood-red paint, a rare instance when vandalism was supported by many in the community who felt the statue, and its place in the city’s commercial center, were a particular affront to history.

Melissa(Queens,New York) photo by France F. Denny

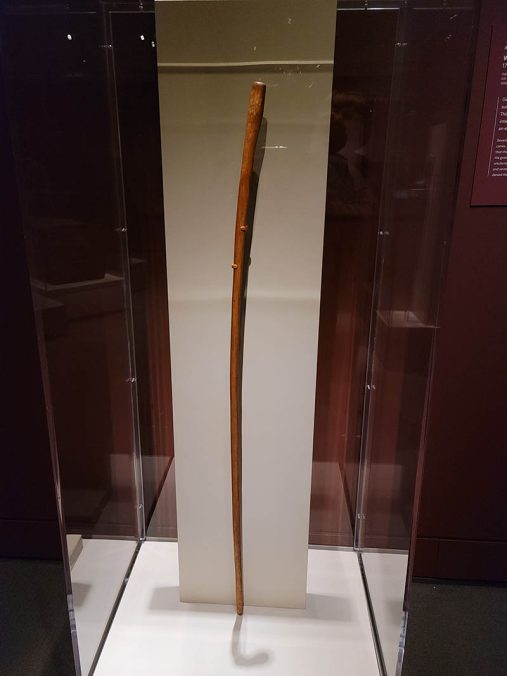

Walking Stick Owned by George Jacobs, Sr. Oak, Peabody Essex Museum

Throwing a pointy hat on anything not nailed down began in the early 20th century to draw tourists to the city’s historical houses and thus contribute to their upkeep. So, 100 years on, it’s become a tradition unto itself. But it bears increasingly little resemblance to those early citizens who were punished for reaping bad crops, or whose means of physical support, like George Jacob Sr.’s walking stick, featured in Major Arcana, were considered “spectral evidence.”

People with an affinity for nature, the mentally and physically affected. People who dared to be different. Women. McQueen represented all of these in his shows leading up to this homage to Elizabeth. Famously, he hand-crafted a pair of ornate wooden legs for paralympic athlete Aimee Mullins to display as she walked in his 1999 show, the occult-teasing, “No.13.” Countless viewers who thought the legs were boots, clamored for a pair of their own.

What, if anything, the present owes to the past, in art and in life, and what separates inspiration from exploitation, are all conversations worth having. At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, those conversations are being had between works themselves, in Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, and Muse, the first McQueen exhibition on the West Coast, which opened just on the heels of Major Arcana’s closing.

“Pairing (McQueen’s work) with different types of art and art mediums and creations, it continues the dialogue to the next step,” says John Matheson, writer and fashion archivist who consulted on the project. “Now we can actually create conversations about things and do a bit of push/pull, some might be uncomfortable, some might be celebratory. It allows, in a very modern way, for us to view his clothing in a way that I would like to think he would really like.”

Two hundred works from LACMA’s permanent collection are paired with various pieces from across McQueen’s career, demonstrating the breadth of not only his contribution but his inspiration, as well as the recurrence of common themes throughout history. The arrangement of works draws parallels between, for example, McQueen’s Spring 2002 collection “The Dance of the Twisted Bull,” and various works from Goya. An Andreas Gursky photograph looks right at home amidst select looks from McQueen’s Spring/Summer 2010 marine-themed “Plato’s Atlantis.” The grandiose and even grotesque references of his runway show’s themes and theatrics are acknowledged by the category monikers of Mythos, for his references to historical movements and religious belief systems; Fashioned Narratives, which show his ability to build new worlds from reimaginings of past events; Evolution and Existence for his fascination with the human condition and the way groups of people live their lives.

Yet, McQueen’s greatest show of reverence lies in the tiny details, for those who look closely. They placed the checkerboard suit from the Autumn/Winter 2003 show “Scanners” collection with a suit from 20th-century Los Angeles-based costume designer Gilbert Adrian (1903-1959), as McQueen continued a tradition of curved seams and tailoring that is somehow uniform all the way around. The final section, Technique and Innovation, acknowledges that McQueen’s masterful stitching and tailoring made it all possible, and made the son of a London cab driver the golden boy of British fashion. Now the man who spent his career paying homage to so many things, has homage paid to him and to his very ability to pay homage, etc… “It continues on,” Matheson says. “It lives beyond just the moment in time.”

Perhaps she wasn’t a witch, but Annabelle Neilson nonetheless confessed to having been possessed of a preternatural– even supernatural–calling that day in St. Paul’s. McQueen’s spirit had urged her there, trusting his friend to speak on his behalf. She could feel it, she said, in the stars.

Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse is on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through October 9, 2022.