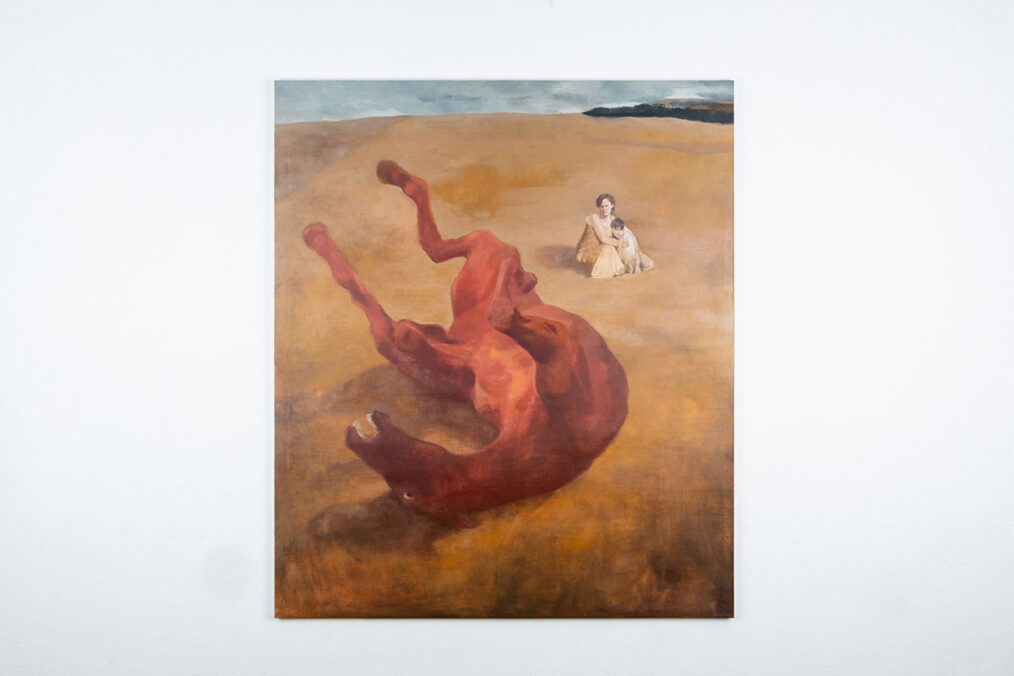

Erka Shalari: I’d like to begin our conversation with the work that appears on the cover of your portfolio. I see two things: whether a miniature horse or a huge dog. Why have you decided to start the narration in this way, and why does the motive continue repeating?

Valdrin Thaqi: Interesting, we started this conversation with this particular work, because it’s the only motive that I work in series with. I have four paintings on the topic, and I can’t get enough of it. It’s quite a personal work and one of the works that connects deeply with my memories of Kosovo. As one might know, we do have an issue with stray dogs, so if you walk any city in Kosovo, it is impossible not to see a stray dog, usually lying in this position as depicted in the painting. Dealing with this problem, the country back then had a rather macabre solution to this problem, shooting them dead. As a child, on my way to school, I would often walk by a military truck loaded with deceased dogs. I think those kinds of images have stayed with me since. But when I think of dogs, they represent unconditional love to me, something that is hard to find among us humans.

The dog lying with its head covered represents exactly this. We have killed unconditional love and covered the face of it, in a tentative way to hide our shame. Anyway, it is common people mistake this figure for a horse, which is completely strange to me. But the horse motif does repeat as well in some of my paintings. That is not necessary for what a horse represents, I think, for me it’s more of a feel. I think whatever you paint, if you put a horse in it, it will always indicate some kind of strange, twisted narrative. It clearly has a strong presence. Except for the work Memory of the world, which is a deeply personal work, since depicted in the background of the painting is my mother and me as a child. It is the only work that is painted directly from a memory.

After my mother passed away, I kept going back to this memory I have with her. I must have been around 4 years old when this happened. Now, in order to understand this work, I must go through the whole story… I spent my first childhood years in Llapushnik, a village located in somewhat central Kosovo. There was this vast field we used to play there, surrounded by an organic fence. Now that I come to think about it, strangely, it was always a barren land. On the other side of the fence, there were horses grazing, but these were labor horses. Clearly beaten and traumatized, on a fine morning day one of them gets crazy in the head, and jumps the fence. Rolling on the ground, stomping and neighing in a very possessed manner. I stood maybe around three meters away from it, overwhelmed from all this sudden action. My mother ran and got me out of the way, while we stood seated at a safe distance, and gazed at it. Now, here the horse figure takes a completely symbolic meaning, which describes my later relationship with my mother. Somehow, I always felt like my mother never knew what to teach me about this world, but nonetheless, she was always there, gazing at it with me, same as in the painting. Must have been hard though, the world is indeed like this crazy possessed horse, which you cannot tame.

Why have you decided on never-fixed meanings, kind of always letting them open for the audiences?

Now you see, at times you have a clear idea in your head of what you want to paint, but that doesn’t happen very often. Once you transcend it onto the canvas, it’s not the same as in your head, and you undergo a process of trial and error. But this is not necessarily a bad thing, it’s actually quite exciting, to surrender to this process. My work does not hold fixed meanings, becuase it acts as some kind of mirror. It deals with the human experience, and I think the audience can relate to that. My work does not offer any answers, but dilemmas instead. Anyway, once you put a finished work out there, it doesn’t belong to you anymore. People will see in it whatever they want to see in it, so you can’t really offer some kind of fixed meaning. And that is the truest meaning of a painting.

I am caught by how you use the white colour. Such as in the work A gift from the depth sea or Homesick III. What flair did you want to give to the paintings?

That must be purely unconscious, but you always have to bear in mind how the color thinks. I completely forgot about that, until a few days ago, I was really annoyed by this painting I was working on and just started playing with brushstrokes without much thought. And there it was, the color thinking for itself. Now of course, you have to think before you put a brushstroke on the canvas. It has to look like an accident, but a very fine and controlled accident. But most of the time, the painting will tell you what kind of color it needs, you just have to listen to it.

One senses a certain melancholy in your oeuvre, and so the question arose for me: is music important to your work? Do you listen while painting, and if so, what would the playlist for your paintings sound like?

It’s fascinating how the emotions in music can resonate and find expression in visual arts. It does act as a silent collaborator that influences the mood of the work. It does intensify things, but I wouldn’t address it as crucial in my work. My choice would be some sort of ambient experimental music.

You often work on a large-scale canvas. What allows you space? Further, tell us something about the process of painting.

Frankly, I only recently started working in large formats. I used to do miniature works mostly. This transition from small to large formats wasn’t just about change in size but also about accommodating and expressing more expansive ideas. It’s about the emotional and conceptual space that comes with it, allowing for bolder brushstrokes, a more pronounced presence, and a different kind of interaction with the audience, creating a dynamic that’s both visual and emotional. I work on an unstretched canvas stapled on the wall. I’m always happy to start a new work, but it’s also quite terrifying at times. Sometimes I will stare at a blank canvas for hours, before I start working. I usually work with references, pictures that I take myself or materials that I find around. But inspiration is everywhere for me. I think as soon as I have this urge to paint, I see everything as a painting. I start with bolder, messy brushstrokes, so as to cover the whole canvas first, and that way it’s easier for me to dwell into further details.

Lately, I’m very concerned with negative space in my paintings. It’s fascinating how what’s not there can be just as impactful as what is. Crafting a powerful atmosphere through negative space requires a very delicate balance, knowing when to let it breathe and when and what to bring into focus. And this is the only thing in painting I believe to be an entirely conscious decision.

Simona Squadrito, writer, curator, and philosopher, throws a very interesting light on your works. It compares it with Magic Realism, painting at the beginning of the 20th century, or the work of filmmaker and artist Michael Borremans. What relationship do you have with fictional elements?

Simona actually introduced me to the term “magic realism”, though I hadn’t consciously thought about it when creating my work. But I’m not sure there are any fictional elements in my paintings. I work with real-life models, I can’t just paint a body that does not exist. I can’t just invent someone. Every person is so unique and complex and I’m particularly interested in delving into the intricacies of the human psyche. The characters in my paintings take shape after spending time with them. While the circumstances I place them in might be considered fictional, they aren’t too far removed from reality. I think what makes them unique is the blend of authentic individuals and situations that, while slightly fictional, maintain a connection to the complexities of real-life experiences. It’s that fusion that, perhaps inadvertently, captures a form of magic realism in my work.

I also see some „ultra-contemporary“ elements, such as phosphorescent nail paint, fashion, and maybe selfie culture.

At times, I get really excited about subcultures and fashion. I love the aesthetics of it, especially how they are depicted in cinematography. I draw a lot of inspiration from the cinema as well, and often incorporate it in my work. I believe there is a very thin line between a painter and a filmmaker. But selfie culture is not particularly something that interests me. I believe it’s one of the ways of celebrating our bodies through new means of imagery. An extension of one’s identity. But this reminds me of the discovery of the mirror since it’s fascinating that the number of self-portraits since its discovery of it, went drastically up. It became a tool for self-examination and self-expression, influencing how people dressed and adorned themselves. I think that’s what I’m after: the essence of the subject and the power play that comes with it.

At the moment you are in Kosovo, what are you working on?

Ah yes, Kosovo. I love this country. It has some unique and unpolished qualities. Since I left the country, I have gained a deeper understanding of its untapped potential. That’s why I continue to return for extended stays. I have my studio in Prishtina, and it’s where I spend the majority of my time these days. Started working on some new pieces, which are bolder and quite uncanny. I’m working on different pieces simultaneously at the moment. Never did this before, since I usually concentrate all my attention on one work at a time, but this way it’s proving to be quite dynamic. That’s the reason that sometimes when I need a break, I can just jump to the work next to it. It can also provide you with insights about the previous work. Quite well aligned. I’m still in the process of understanding and refining them, but it’s a lot of fun.

How do your ateliers of Berlin and the one of Kosovo differ? Can you tell us something about their respective moods?

It differs significantly, although they both offer some real contrasting advantages and challenges. Berlin’s vibrant scene provides me with a lot of inspiration, but it can be a double-edged sword because it also distracts me from my ideas. Whereas Kosovo’s more tranquil environment and also the spacious setting in my studio allow for a more consistent, inwardly focused flow in my work.

How does a day of yours look like?

I usually wake up early in the morning, I make myself a cup of coffee and find something to read, whatever I can get my hands on. It’s my favorite time of the day. At the moment, I’m reading Triptych/three studies after Francis Bacon. Quite interesting, it puts in parallel the work of Bacon and Rothko. Would have never realized. I take my breakfast at around 10, scrambled eggs, tomato and white cheese are my go-to. Then I lock myself up in the studio for another eight hours with some occasional coffee breaks. In the evenings I love to cook up smth good for myself, and do some research later, or watch a movie.

Valdrin Thaqi (b.1994, Skenderaj, Kosovo) graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prishtina in 2019. His artistic practice includes painting and installation. The artist lives and works between Pristina and Berlin – www.instagram.com/valdrinnthaqi.