The language of Un Paradiso Amaro/Bitter Paradise is a poetic one, the same as its title, however it does not make it less political, on the contrary – it is radically poetic. Based upon artists’ solidarity, responsibility, and care, not only does it shed the light on the tragic disappearance of Teresa Feodorowna Ries from the art history but empowers the spectators with an emotional story of fight for justice.

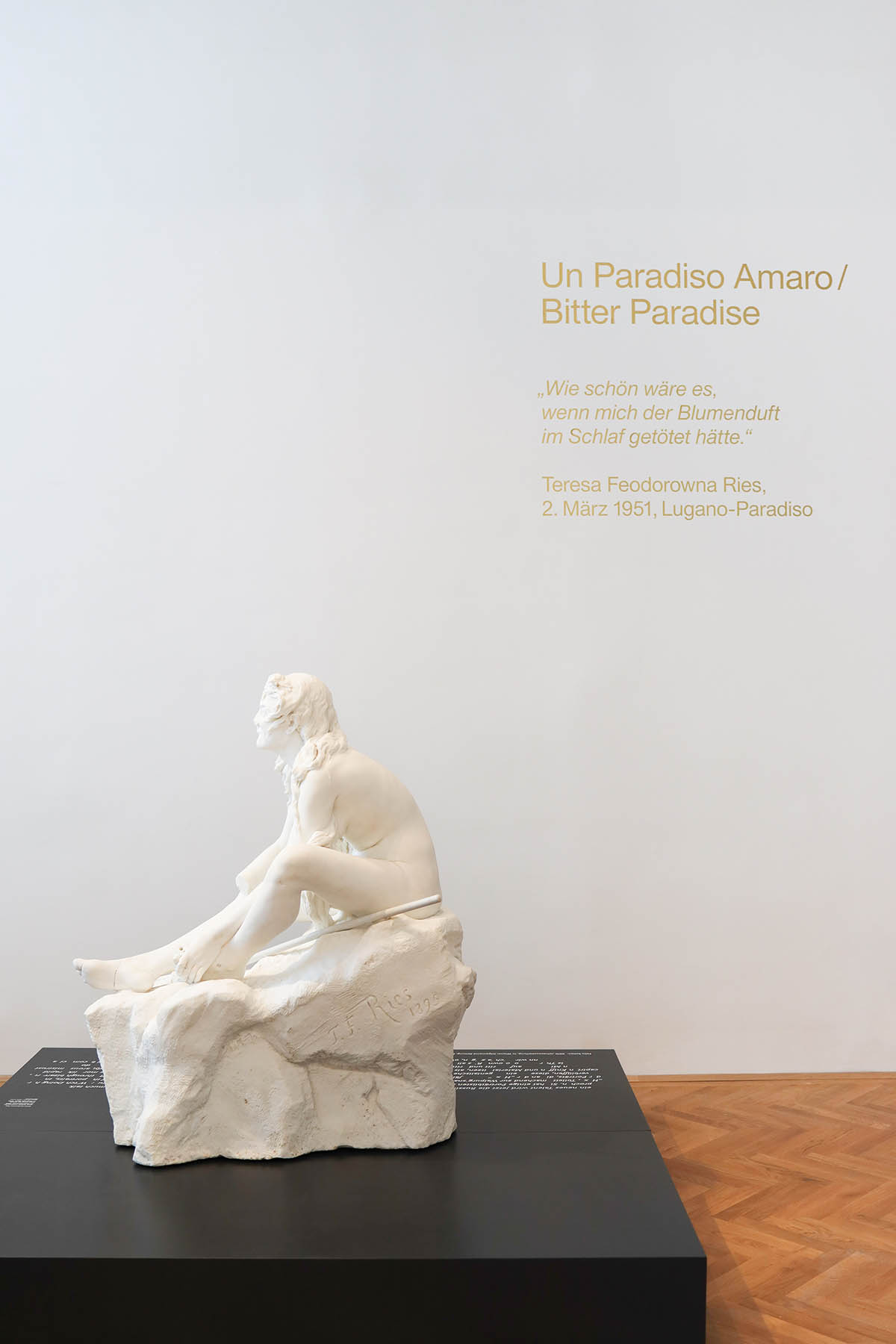

The exhibition begins with the sculpture Witch Doing Her Toilet for Walpurgis Night (1895) that has been propelling the entire story. In 2019 it was shown at the exhibition City of Women in Lower Belvedere, along with the other artworks of Teresa Feodorowna Ries and her female peers who lived and worked in Vienna from 1900 to 1938. Inspired by the seminars of Simone Bader, Valerie Habsburg came to see Ries’s body of work and was so impressed by the energy and expressiveness of the Witch, that decided to do some deeper research on the artist. The scarcity of information brought Valerie, in her own words, to ‘the twentieth something’ Google page when she came across a passed lot of an auction house in Monaco – the personal archive of Teresa Feodorowna Ries, an artist of Jewish descent, who was born in Budapest, grew up in Moscow, made her brilliant career in Vienna and died in exile in Lugano. Contacted the house and found out that nobody had been interested in it, Valerie purchased the archive for a very moderate price. The artist herself, led by inspiration and research drive, she drew this folder almost intuitively out of the darkness, without yet knowing what exactly was inside and what she would do with it. In this way, Valerie became an owner and keeper of Ries’s private documents and correspondence, diary, photographs, list of artworks, newspaper articles as well as handwritten last will and testament. However, apart from the excitement of discovery, the acquisition motivated the artist to embark on a mission – to re-establish the artistic legacy of Teresa Feodorowna Ries, to fulfil the terms of her last will and to erect a tombstone on her forgotten grave.

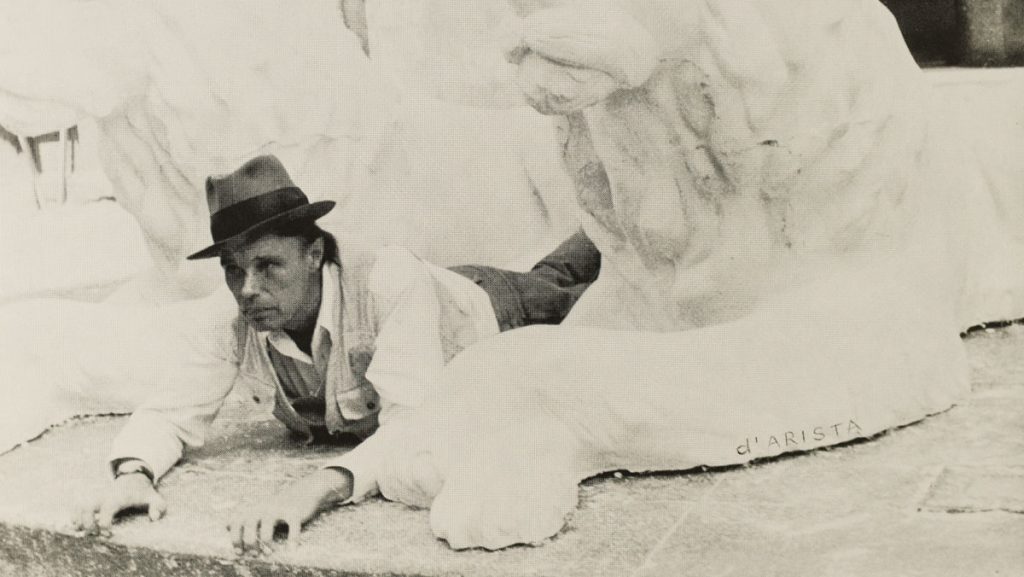

Anka Leśniak, The Reconstruction of the Witch (2019)

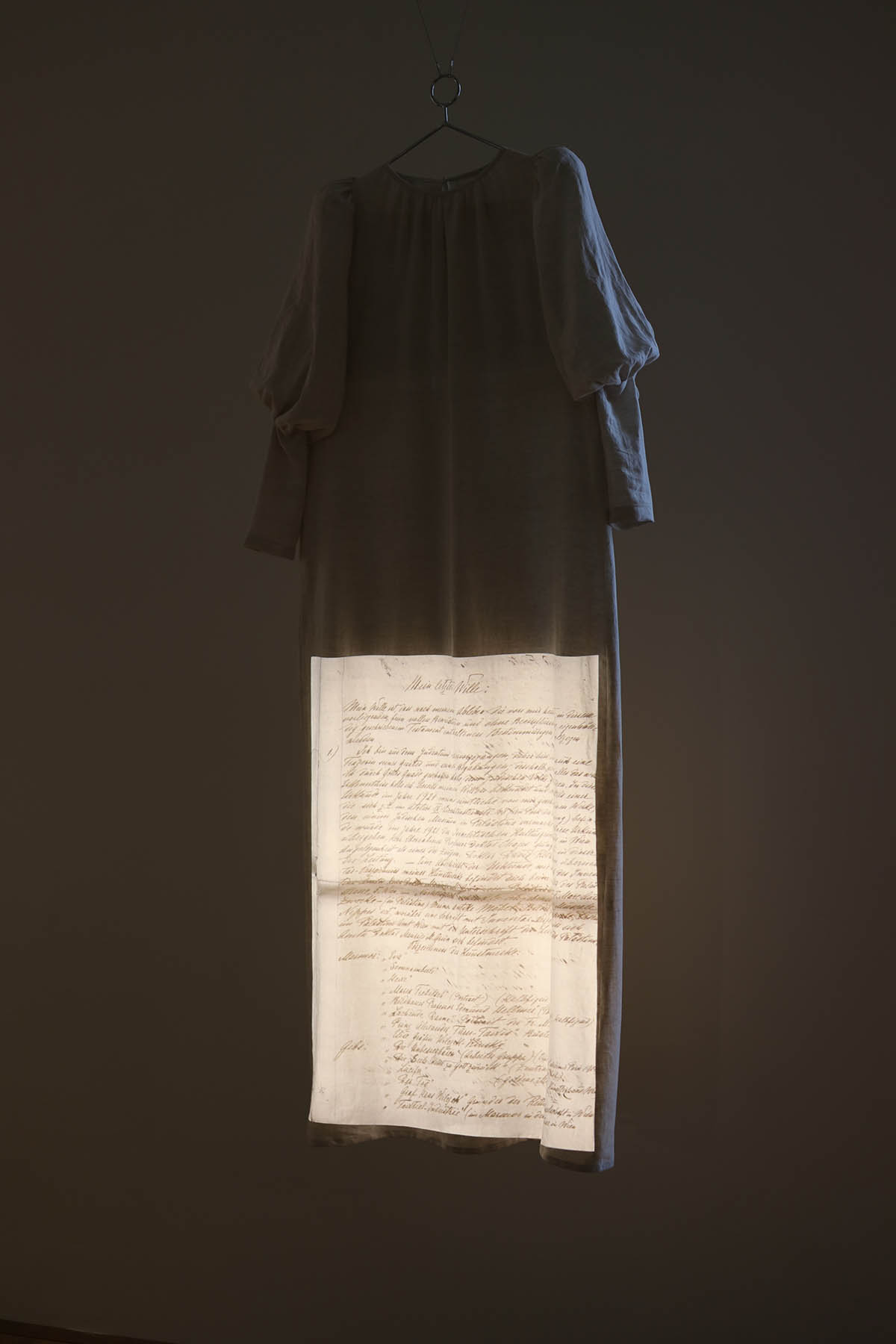

Judith Augustinovič and Valerie Habsburg, The Kittel, 2021

In 2019 TFR Archive¹ was founded, and different artists were invited for creative collaborations. Mika Aya Azagi, Anka Leśniak, Judith Augustinovič, Anna Bochkova, and Sami Nagasaki joined the working group. Each of them had their own path of discovering the art and persona of Teresa Feodorowna Ries. Un Paradiso Amaro/Bitter Paradise, curated by Valerie Habsburg with curatorial support of Elke Krasny, is the first exhibition to share their research and outline its potential development.

Anka Leśniak took an interest in the issue back in 2015. From her film The Witch (2016), based on Ries’s autobiography and made as a first-person narrative, we find out that the sculpture happened to be the first work Ries exhibited in Vienna. Provoked her male colleagues and attracted the attention of the emperor, it stirred the public and made her famous overnight. Witch Doing Her Toilet for Walpurgis Night is a rebellious and subversive take on the iconographic image of The Toilet of Venus. Usually, it depicts a voluptuous woman taking care and adorning her body in an opulent environment; served by entourage, she often enjoys her reflection in a mirror. Yet Ries sculpted a dramatic figure of a woman with dishevelled hair, sitting hunched over to clip her long toenails with shears; pointed cunning features on a round face and lascivious mouth make a strong countenance – she seems to anticipate some savage pleasures. In opposition to passive Venus, awaiting to be observed and judged by the male gaze, sensual and powerful Witch claims the right for her body, she has it for herself and does not care if it fulfils any conventions. It is an artistic statement, indeed. Engaging the folklore character, Teresa Feodorowna Ries re-interpreted it towards a feminist model and re-discovered its genuine riot power.

Unfortunately, the Witch was partly ruined during the turbulent 20th century, among the big losses is the hand holding the shears. In the artwork The Reconstruction of the Witch (2019), Anka Leśniak seeks to trace the damages of the sculpture. For that she interviewed two restoration experts – Marija Milchin, from the University of Applied Art in Vienna, and Johann Nimmrichter, from the Department of Conservation and Restoration of the Federal Monuments Authority in Austria. Still, it is all opaque – when and how it happened. Perhaps, the biggest damage occurred neither during the Nazi regime, nor bombing of Vienna, but afterwards, when the sculpture was exhibited in Oberlaa at the International Garden Show in 1974 and where it was left (or forgotten?). Destroyed and vandalized – with chipped off small details like parts of the curls and tiptoes, red-painted face with holes all over, and missing hand – it was found in the early 1990s. Reported by the art historian Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber, the Witch was finally relocated back to the storage of the Wien Museum. So far, it remains a mystery why the museum loaned the piece for the outdoor show and let it stand there unattended for almost 20 years, exposed to weather conditions and vandalism.

Following the tragic journey of the sculpture, Leśniak, sees the loss of the hand both symbolic and symptomatic¬ – carrying the sharp shears, it evokes castration anxiety. In her research article for Art and Documentation², the artist questions if the limb could be broken off due to the fear of emasculation or fetishism. As if it were to restore the power of the Witch, Anka creates an installation The spell with scissors (2021), in which various suspended scissors come into motion when spectators approach them – shiny metallic tools re-awaken the image of a malicious smile at the Witch’s face. They cast an eerie shadow on the wall, over the projected video, filmed in a sculpture atelier with women artists in action. Repetitive and loud movements of stonework appear like rituals, they rhythmize and sound the space.

Mika Aya Azagi’s video art project also engages rituality – meditatively slow covering of a face with found rocks in Skin/Stone (2019) reflects the experience of the material on a somatic level – to merge with it, to feel it weight, natural texture, and temperature. Concerned with Teresa Ries’s passion for stone, Mika sets on this journey to discover its viscerally, by interacting spontaneously and letting the body perceive and response. Through her irrational but caring gesture, cold, inert rocks suddenly transform into a sensitive and spiritual substance. The artist questions the bitter situation that for the sculptress, who dedicated her life to marble, no tombstone was put up, and so Mika creates a stone mask over her face which moves together with her breath and becomes a performative monument.

Across the room, there is a white linen kittel or working robe for sculptors, used to be worn in Ries’s time. Watching through the artist’s photo album, one notices her wearing this typical gown, although back then it was meant for and seen on men mostly. Her intention to wear it and to be photographed in it reflects her attitude – she passionately pursued sculpture and that also needed dismantling patriarchal stereotypes around the field – for centuries it had been identified with men’s vocation exclusively. Dressing this way, Ries declared herself equal to the male peers and encouraged other sculptresses to enter the field with an open mind. Her commitment to integrate women into the profession and boldness to be an example to follow are proofed by her application for a professor position at the Academy; dated 1931, it is the first one written by a woman. However, it was never answered. As if it were to manifest the ongoing struggle, the artist’s found testament is projected directly on the kittel. In their installation, Judith Augustinovič and Valerie Habsburg combined these two important elements to transform them into a monumental tribute – a will for art, embodied in the working dress, and the last will for the artworks, yet publicly presented. Here we read that Teresa Feodorowna Ries wished her sculptures (her children as she called them) had been donated to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

To fulfil this last will, Valerie Habsburg has been intensively negotiating with the Wien Museum. And finally, Teresa Ries’s sculptures, including the exhibited Witch, are subjects of provenance research conducted by the Vienna Restitution Commission.

Mika Aya Azagi, Skin/Stone (2019)

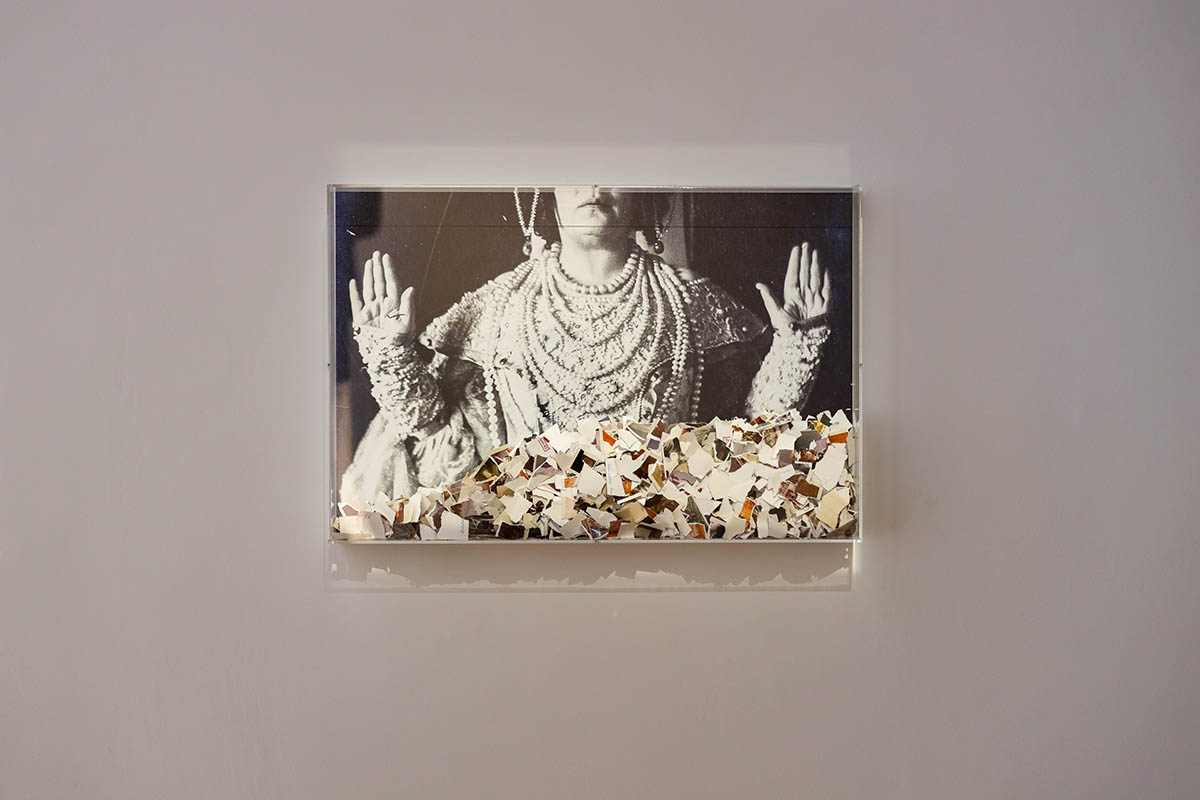

Valerie Habsburg, The measurement of time, 2019

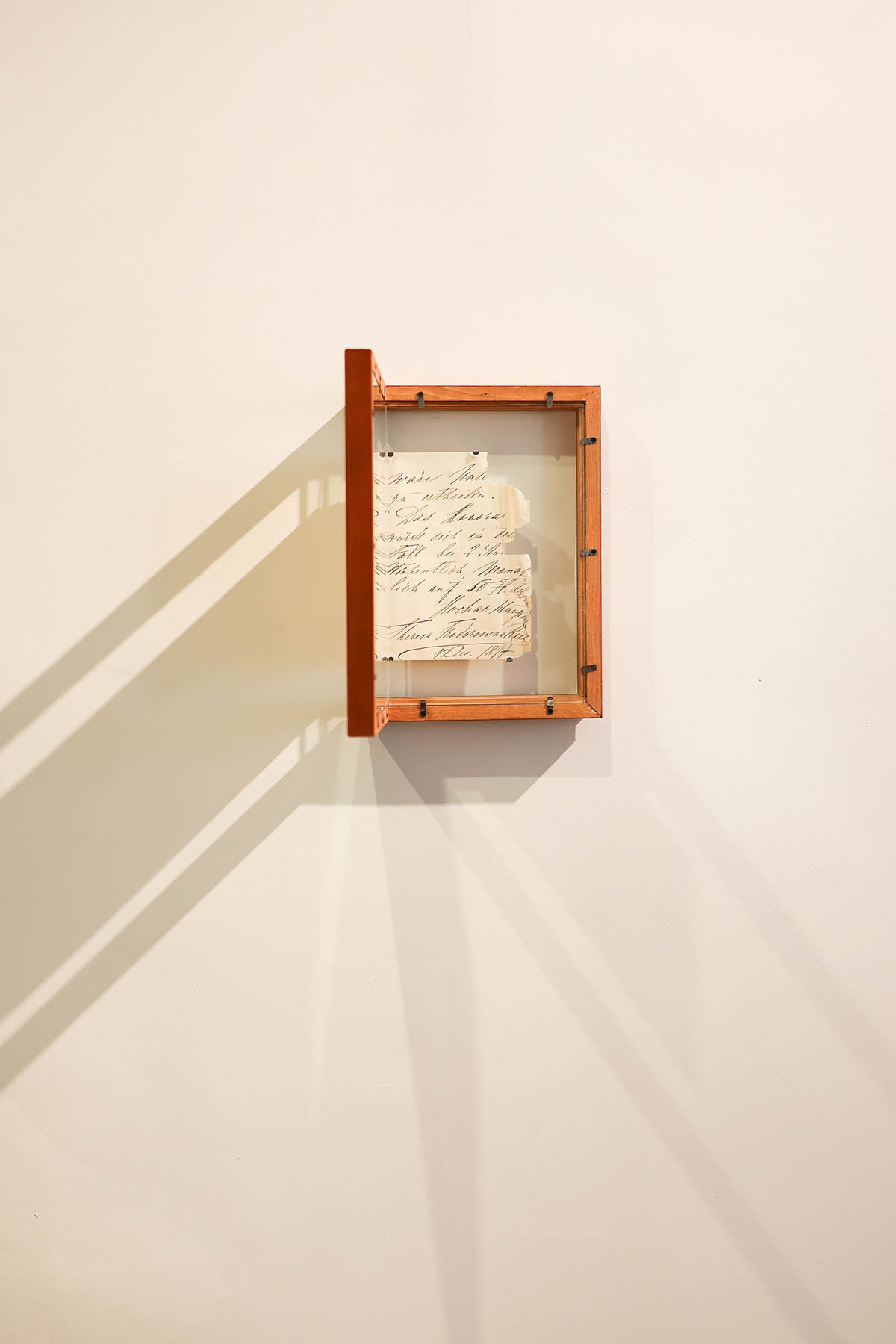

Next to The Kittel (2021), there is Declaration (2021) by Sami Nagasaki. It is an actual letter of Teresa Feodorowna Ries to Mark Twain who happened to commission her a portrait sculpture. Beautifully penned, it expands on the notions of space and time. Now double-folded and framed the way that one part protrudes from the wall, the letter evolves into a sculpture itself and epitomizes the written ideas. ‘Manuscripts don’t burn’ – a famous phrase from the novel “The Master and Margarita” could have become an epigraph for the entire show, because the very writings of the sculptress – the autobiography, correspondence, diary, handwritten lists and records – made it today possible to restore her legacy. Yet the meaning of the phrase is much bigger, it speaks about true art never disappearing into oblivion, but always coming back, rediscovered and relevant anew.

In the centre of the room Anna Bochkova’s group of sculptures – Witch’s Spaces/Teresa Spaces (2021) – is placed. Anna drew her inspiration from Ries’s autobiography “Language of Stone” that was written in 1928 and a copy of which can be found in the Academy Library. The works appear dream-like, with organic forms meeting architectural structures. From the solid plaster objects thin and flexible tentacles sprout out, curl, and intertwine, wrapping them around. Their whimsical shape refers to the language of the book – vivid, poetical, impulsive, while the structures represent the strong story about a persistent battle for one’s art to be acknowledged.

Another Anna’s sculpture – Hexe (2020) – stands close to the Witch. Made of papier-mâché, spiky body looks fragile and dangerous simultaneously. It might take its inspiration in a jellyfish. Transparent and fluorescent, those marine creatures are mesmerizing in their way to float, but often very poisonous—here Anna reinterprets the idea of a witch and finds new imagery to speak about concealed powers for radical change. As witches cast spells and magically alter the course of life, so do medusas – first hypnotise with their alluring beauty, then sting and fatally intoxicate. In the autobiography, Ries told a story of how the idea of the witch came to her mind. Once walking along the corridors of the Academy, where she used to have her studio, she noticed a broom standing in the dark corner and suddenly it sparked her imagination: “Beautiful hands and feet, toilette, broom, witches‘ Sabbath, a witch who so enchanted and enchants, who has power over humans, power, power – my fantasy took flight, and my thoughts had taken form”³. Isn’t it about the power of transformation? The broom, which is associated with women’s domestic labour, in the hands of the witch becomes a magical flying vehicle transporting her to the boisterous celebration of Walpurgis Night. Sea jellies, for their part, demonstrate unique transformation ability in adapting to climate change, for they thrive there, where other species extinct, and form thus powerful medusa communities.

By displaying the documents and art projects together, Un Paradiso Amaro/Bitter Paradise narrates not only a life story of the talented sculptress, but also a story of the wonderful finding that triggered a chain of important events and shacked up some deeds kept deliberately obscured. The forgotten grave of Teresa Ries in Lugano is found, the Restitution Commission has launched the provenance research of her artworks kept in the collection of the Wien Museum, several scientific papers on her artistic legacy have been published in German, Hebrew, Polish, English, and now the exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts, her alma mater, is taking place. Bitter to know, that so far, among the institutions, only the Academy has been supporting the initiative. It is therefore all the more moving to realise that almost everything has been done by the artists independently, driven by a genuine fascination with the œuvre of Ries and sincere desire to share it with diverse audiences. All but two of the contributors are women, so their endeavour towards justice and acknowledgment can be seen not only as a personal intention, but peer solidarity with a colleague, a predecessor who was struggling for their rights to study, be artists and be treated equally within the art community. Participation of Sami Nagasaki and filmmaker Karl Martin Pold reassures that feminist projects are relevant and important for all of us.

Sometimes we think that everything is found and discovered, that nothing new can come or be made, whereas Un Paradiso Amaro/Bitter Paradise proves otherwise – there are more persons erased from the history, more voices made silent, and more things gone into oblivion. And it is our collective responsibility to bring them back and tell their stories.

Exhibition: Un Paradiso Amaro/Bitter Paradise

Exhibition Duration: 09.10.2021 – 16.11.2021

Address and contact:

Exhibit Studio, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna,

Schillerplatz 3, 1010 Wien

www.akbild.ac.at/

¹ See www.teresafeodorownaries.com

² See www.journal.doc.art.pl/pdf21/art_and_documentation_21_teresa_ries_studies_lesniak.pdf

³ Teresa Feodorowna Ries, Die Sprache des Steines (Vienna: Krystal -Verlag, 1928), 13-14. Translation based on: Julie M. Johnson, The Memory Factory, 209.

About the writer: Liudmila Kirsanova is an independent curator and writer, whose research is focused on autofictions, storytelling, and politics of belonging. In 2019 she became the finalist of the curatorial award Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm. Curating international and domestic projects, Kirsanova has been advocating and promoting female artists, in particular those from non-Western cultures.