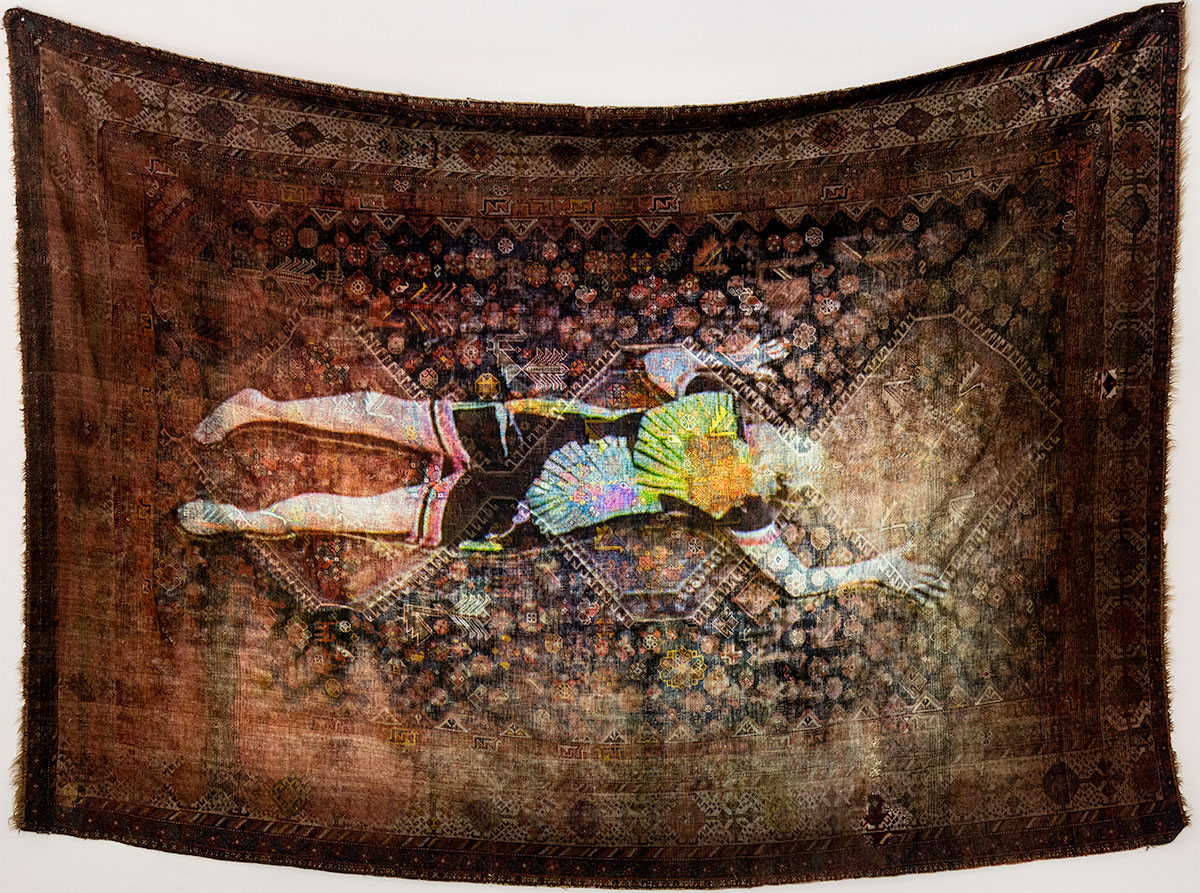

We decide against taking the elevator and after a few minutes, we find ourselves in the entrance area of the studio. We stand amid large-scale artworks – all these works have just returned from Widauer’s most recent exhibition. Now they have been distributed in a new order over the long corridor areas.

Erka Shalari: The name next to your doorbell is not yours. Is this maybe connected with an exhibition that you had during quarantine?

Nives Widauer: Well, there is the name Balatsch on door number 7. When I moved into this apartment, everyone said that this place belonged to a couple who had lived here for 60 years and were totally happy. The house was built around 1900 by a tenor of the Vienna State Opera and was for many years inhabited almost exclusively by musicians. Mr. Balatch, which died a few years ago, was the director of the State Opera Chorus. So, I did not change the name in the first days and then after a while, I kind of started to like this name. In the first year of living here, I used to send all the post that was still arriving here to the couple. One day they wrote, „It is very kind that you send us everything, but we don’t need it anymore. We wish you all the best in this place where we were so happy, and we wish you the same.“ This was a very lovely letter, I must have it somewhere here. Then, in 2020, I had a show with the NY Philharmonic about the first female musician of this orchestra and I rented out my place to a young Italian curator. On the 7th of march, I had to come back because of the pandemic. The young curator could not return to his family. If you remember, it was not easy to travel during the first lockdown. So, we kind of spent the lockdown together. During this time, we decided to make a show together because at that time I had an appointment with Hinterland Gallery, but as everything was strange, we decided to make a show about 30 years of COVID, a throwback. So, Pietro Scammacca, the curator in this show, is a fake 54-year-old curator. In fact, he was 24 years old when this happened and I was fifty-something, and in the show, I am the eighty- something artist. I named the show „Living with Anna.B“ because Anna is my second name and B is Balatsch, the name that you saw at the door. That is how the story started. Now the name is still there. And I am pretty convinced that I will put my name down there before I leave this place.

Would you like to tell us more about the story?

I think it was the 6th of June of 2020, and this show was one of the first shows that opened after the first lockdown. It was probably the first get-together for many people, and we made this throwback 30 years of COVID and invented a story. In this story, I live in Sicily, and I am at that point in time the godmother of Pietro’s twins. We kind of invented the story; then, I had to make artworks for the future. So, I made for example future artworks for 2036, and I was really thinking, „Uauu, what I will do in 2036?“. I thought I will really try to be in balance. Balance can be either mentally or physically, or even when being dead, I will be in balance. Death kind of balances out most of all lives probably. So, I started to do a series of my future artworks. Regarding Pietro – he is a very nice young curator, which I appreciate a lot, now working for Museo Madre in Naples. We got to know each other very well because it was an intensive time for both of us.

Then, for me, creating this show, and inventing this concept was also a way to step out of the crisis. It was a good move because it gave us a fantasy that this could be over once.

I was wondering why Pietro and you decided for precisely this amount of years?

I do not know why these thirty years. I think 30 years is a kind of, „Ok, that is a really safe space“, and at my age 30 years is even a courageous space. But yes, this concept came out of our intuition.

While talking about conceiving artworks for the future, your last show also comes to my mind: „The cabinet of the archeologist of undefined future. Nives Widauer, works from 1979 to 2036“ at Galerie Rauminhalt Harald Bichler. Is this in some way connected?

Yes, because in the vitrine was a little sculpture that I made in 1979. It is one of my first artworks that I made by purpose, not those ones previously that I was just doing just like that, by using clay… The sculpture depicts a baby in the arm, and when I was at this age I really knew I want to have a baby. I saw my future then. So that is how artists are connected to life and how life is connected to artists.

While watching your past exhibitions, I got the feeling that in many of them you like to display works that were made in different moments of your artistic career. Why is that important to you?

I would say that this is a complex net. My own work is a net, filled with patterns, and layers, which all connect to each other in a way. So even the works I did 30 to 35 years ago, I find utterly related to what I do now, even if it sometimes looks different. So, for me is totally natural to take stuff from various periods of time, because time is not linear (…). Our life is like an inhale-exhale thing. I think even an artistic Oeuvre does the same – inhaling and exhaling – it is all connected. You cannot dismantle one thing from another; you cannot cheat on these phases. You had a phase when you were 20, 30, 40, 50, and so on as long as you live, all these changes connect to each other, and you do not have to hide them. A younger phase will show other living traces, then an older phase. But artistic work and life is not about hiding. It is about sharing and being osmotic.

You have developed a whole system of abbreviations (P, V, I, VI, T, B, F, VP, K) for showing the media that you are working with. I was wondering how people were judging artists who were having a multidisciplinary practice back then?

That is a very old system I made 20 years ago or even more when I started my website. These are still the same abbreviations. You are the first person who takes notice of that, or that really mentions it. Maybe the system is a bit childish. Before I had a website, I was an artist for many years. When I started it was not so common that people would work in so many media. It was even a little bit like, „Mmmm, this cannot be serious“. Or they were thinking „Oh, you do not have your language“… In our days this is much more accepted.

What’s the beauty of working with multiple mediums, or for example returning to a medium that you’ve left dormant for a while?

You know, you spend your life in a building. It could be a house, it could be a castle, it could be a (…). Even it does not have to be a real house, there are many rooms, many spaces, and they all have doors or holes, they all have openings, windows and I think that you can walk to one space and in this space, you have the memory of this other space that you have been in, or in the space there is a door to another space again and so on. When I started to work in different media, it was a very similar experience to dreaming. In the dreams, you can in one second be everywhere, no? I think art itself or artistic work itself for me has some aspects of dreaming because on the same day I can walk from one space to another one far away. About leaving things dormant – I also use the expression „putting projects into the freezer“ because I know that sometimes it is not the right time. I love the projects, but I have to forget about them, and all of a sudden they reappear in life. The same as in nature.

Some plants have seeds that take years to sprout, some bacteria survive in the eyes for long times and nobody even realizes that they are there and then the circle starts again. It is a lot about not being afraid of losing something. For me, everything is there and if I have enough time and enough concentration, I always find these places again.

This is also how I use the media. I have to say, that I am a very curious person, so for me working in different media means that I work a lot on different techniques, which is learning, and I like to learn new languages of expression, new languages of techniques, new languages of behavior. Furthermore, each media is connected to the people I am working with, so it is a big network of friendships with a lot of people that is more or less like family life. I can be also connected with a living or dead person, writers for example; trying to understand what these people wanted to tell me or to the world.

What do you usually read?

I usually read several things. Since the situation in Ukraine hit us, I must say that I was not even able to read one page because I could not.

You have worked a lot with video. I’ve noticed that your videos are often silent; sometimes a recurring element is also the loop. I’m thinking of videos such as cambium, monitorlove, de godard à godard, sliding. I am interested in the sentiment that silence and repetition evoke in you.

When I started as a video artist in my earlier years, I did some very big installations that were silent, with my body, fire, and water. Some of them were also part of set designs because earlier I was doing also video set designs. Very early I would say (smiles). It was the late 80s, the beginning of the 90s, so I did not see why it always had to be a sound in it. I did not project them the way you see them now on the internet because I used to make stills off these videos and then project on them, and my name for this was symbioscreen at the time. So, there was a lot of silence. But then I also did literature or poetry, like videos that were not filmed. They were so to say mental videos, where the language was important. And the loop, I really have to say that I love the looping. The looping was something for me, already in the beginning, that makes me (…). It is like a kind of meditation. Actually, I have a huge archive of videos I made that I have never published or shown. At the moment, I am a little bit thinking of maybe working on this kind of exhibition where I will review all my loops, which will be a considerable work. I created so many hours of videos, so I never had the time to really make a review of them. I also like to cook, and meet friends, so this means that I am also not the whole time working.

At the same time, they are very Avantgarde. When watching them, I had the feeling that they haven’t been recognized in the way they deserve to. What is your take on this?

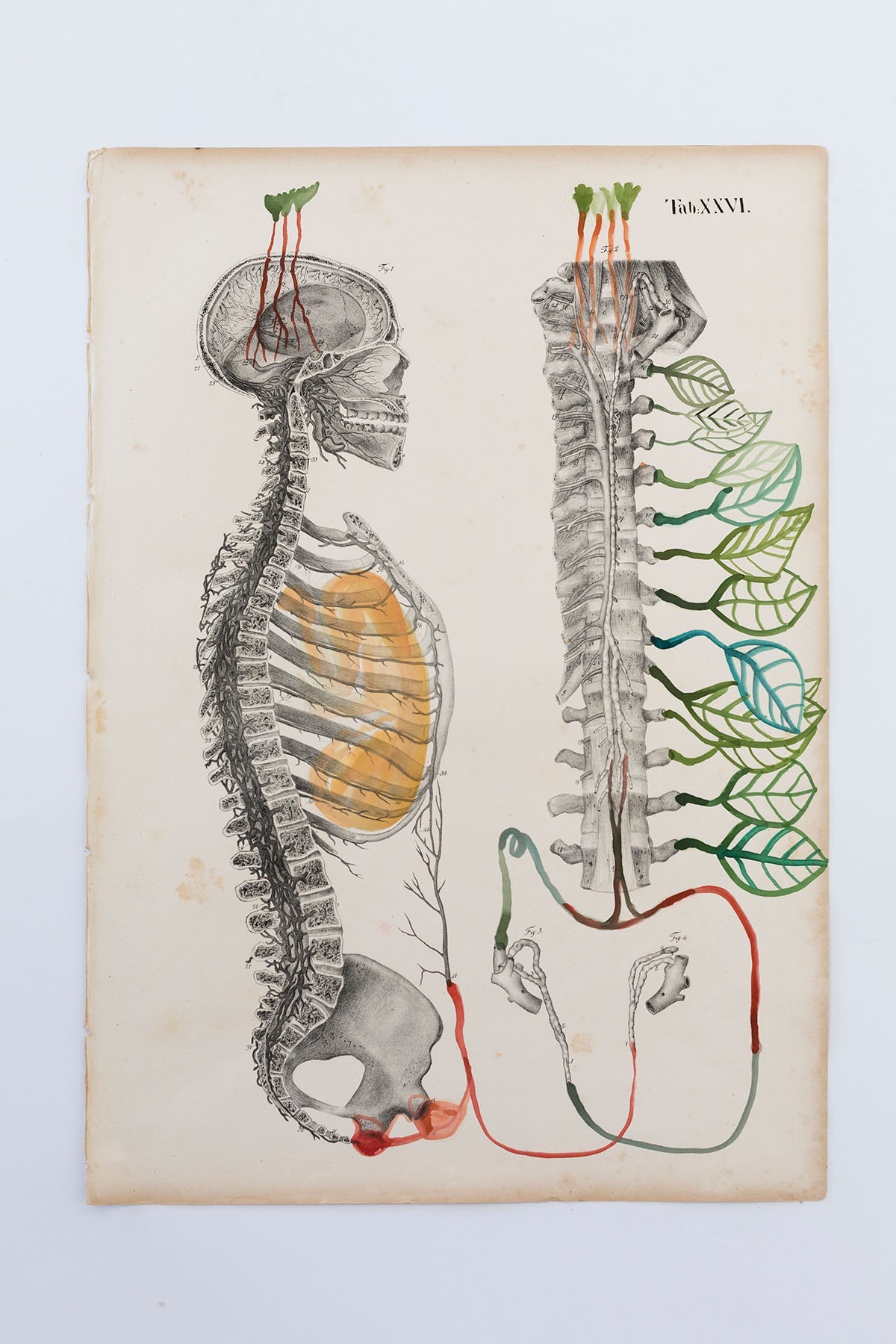

I would not blame the world for not having seen my videos because I, at 25 became a mother and I was very much traveling and not very much following my video art career. I was not in the network, although I was studying in the very important class of Kunstgewerbe Schule Basel, and I was studying together with some of today’s most important video artists, such as Pipilotti. My focus shifted. It was not that I did not want to be an artist anymore, but it was challenging to follow up networking, and at the time, being a mum was not very much seen as being possible for an artist. There were even some curators who were telling me, „Someone who has a little baby cannot make art.“ But this has also changed a lot. You know, each human has a rhythm in life. I think that this is a very good time to review all those works. And I am continuing to do videos. The works with the tapestries, for example, are already a new work, where I have filmed several loops in 7 dresses, on seven different tapestries. So, I am ready to show completely new video installations – which very much focus on analogue digital.

Let’s talk a bit about the video of yours – Todesfuge. There are so many elements that struck – the female figure, her running, the scenes on the church, the surreal rail system that emanates the church altar with the Jasomirgottstraße and then various signboards of adjacent sites: Shanghai Restuarant, Meinl Bank… What did you want to portray with this work?

Shanghai was very important, you know why, because is the Todesfuge by Paul Celan. It is the most important work about Auschwitz and I was a very long time thinking, „Should I do that?“, and I was talking to Stephansdom people, and I was telling, „I want to shoot this video in the catholic church“. Then, I had in my mind that this long camera which has rails looked like the trains that were going in Ausschwitz, so I prepared the shoot in one take. There is only one take!!! There is no cut! While she came out and ran and then you see this Shanghai thing; Shanghai was on the point that Viennese Jews went as refugees. I thought, „Crazy that in front of this church you have this place called Shanghai“ and then she runs and goes back to the church. We went, we traveled back with the camera, and then at a certain moment, even when we came out the light was shut down, but this is not because I wanted that, but because the battery was empty. As all kinds of things, that can happen sometimes. She runs back, and when we are at the altar, she is there back again. I had this idea to do all these things in just one take. It was complicated. We were also never trying it out. We had only one night to build it up and at seven o’clock we had to be out of the church because of the first Gottesdienst. Was a totally crazy thing and it was the longest rail for the camera at the time, we had to collect all the tracks from all over Austria in order to build such a thing and the funny thing was that on the night that we prepared that, we had this little sofa that we used because after this shooting we went to the Kunsthistorische Museum to shot this Belvedere view, Canaletto View on Vienna and we had already this little sofa with us and then the owner of Café Hawelka at 2 o’clock in the morning crossed the Stephansdom and sat there for about one hour; I even have a photo somewhere, she sat there watching everything.

I am interested in how this work has been received.

I got a little bit of money, then was shown on TV. I had it once or twice in festivals, but I almost had very, very little response compared to the importance of the topic. Andrea Eckert was very brave; she wore my dress and then this dress she wore was my preferred dress and then I gave to her as a present. I hope she still has it.

Was it perhaps a way to connect by giving your dress?

Yes, I always love to connect on a personal level too, because each project is something that I do from the bottom of my heart, but I am very, very happy that I did this. I made a lot of projects, where I did not understand why I was doing them, but I had to do them.

I’ve read that you’ve used as well other names in your works, such as Blanca, Blansche, Nix (…). Can you elucidate a bit on this fact?

My parents gave me this name Nives, which is not so common name, but it means white, or snow and it was always very special to have this name. Especially, to grow up in Switzerland and then to live in Austria, where everybody asked me about the name, and so I started to use synonyms of this name for different exhibitions or work cycles. In a way very simplistic synonyms of my name.

El Sueño de Blanca 1-7 is based on dreams of yours. What is your relationship with dreams and which dreams do you refer to here?

The point is that I kind of grew up with dreams, because, as you heard this evening, for my family dreams were an important thing to talk about, and for me it is very normal to talk about my dreams. I also wrote down a lot of dreams in my life. The first El Sueño de Blanca was a very strong dream that involved the house in Hietzing where I lived when I started to live in Vienna for the first time. I found out much later that the place was aryanized, and the dream kind of showed me everything that happened. Not everything maybe, but it symbolized what occurred in this house. When I left this house, I shot this on the here present carpet.

Then I wanted to do these with some other dreams, so I started to summarize and somehow depict their feelings and essences. So, it is not things that are told word by word. These are the feelings and you know each dream leaves a mood. Often you cannot name it, but you can tell, „This is the feeling it leaves on you“. I tried to put these feelings in El Sueño de Blanca 1-7. I hope I can show it soon as a group.

Your relationship with the Naschmarkt… While I was trying to formulate questions for our interview, I remembered an article I once read about a men from Rome, who was fascinated from flea markets and was considering people who buy on them as real custodians of other people stories. I have the feeling that quite often are people from outside the family who evolve this kind of sensitivity. Some of your works are also created with flea market objects. Do you also visit flea markets in other countries?

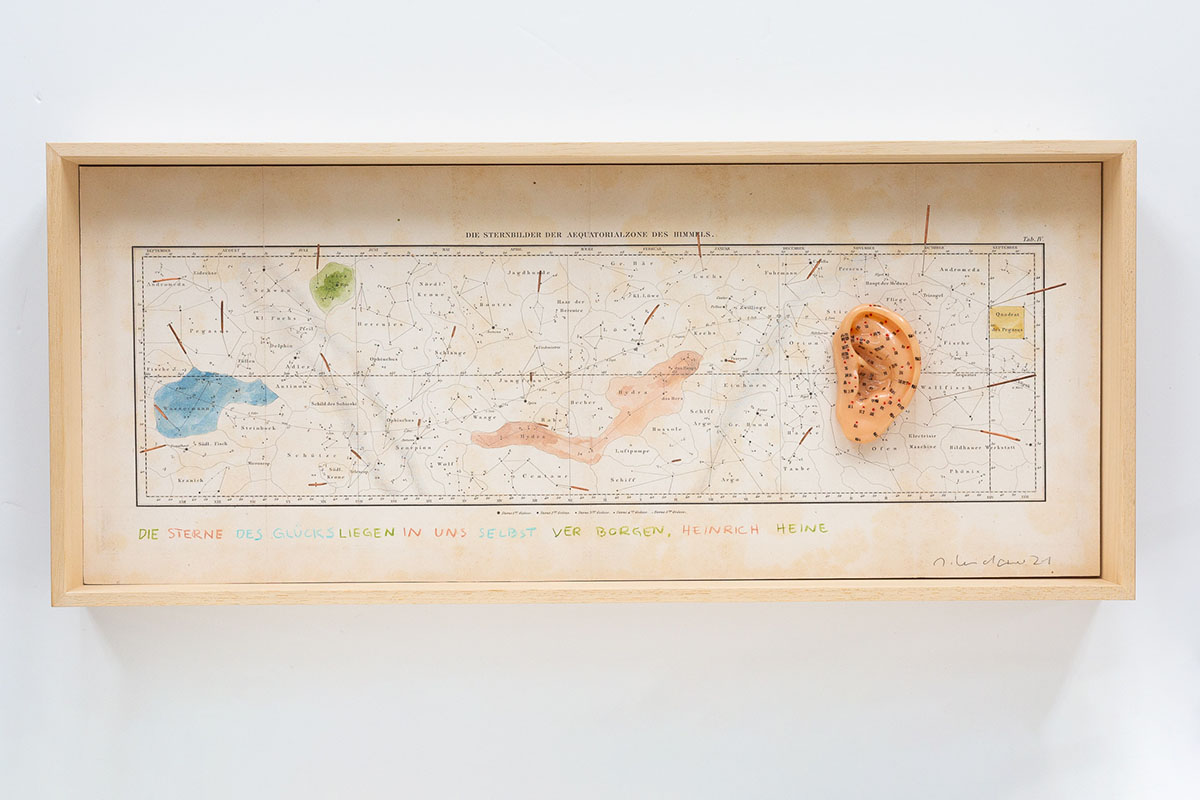

I will show you something from Porta Potenze Rome, November, Sunday. Is so funny that you talk about this because the latest work of the show – the ear and these needles (showing us the work) are from Porta Potenze. It is not that I want to, how can I say it (…) I am not trying to build surrealistic art. I’m just trying to find interesting objects that talk to me. Is more like transformation. Flea markets can be really (…) each object has a story, not only the stories of the objects, but also the stories of the owners. My art also refers to these stories. I can just see the history of this object, but of course it is not so easy to say (…) I love to be at markets in general, not only at flea markets. I like the market as a principle. When I’m in a new country, the first thing that I do is go to a market, and I see what people buy, what they cook.

*On this evening, Cornelius Wildner is an observer, a listener. He will record the interview and thereafter deconstruct it, leaving out all the words and focusing on what is left – the silence of all of us, the catching of breath, the sounds that arise when we prepare ourselves to speak, when we try to transfer the inner world into the outer one. Between words (09’14”) is what remains from a very personal interview with artist Nives Widauer (55’07”)

Nives Widauer – www.widauer.net

Nives Widauer, born 1965 in Basel, Switzerland, lives in Vienna. In 1990 she graduated from the Class for Audiovisual Arts at Schule für Gestaltung Basel. Parallel to the first exhibitions (video installations) she created live video sets for various theatre and opera houses and independent semi- documentary movies. Various Art Awards, scholarships and exhibitions followed. Over the last twenty-five years Nives Widauer’s Cosmos grew in somehow concentric circles up to her resent work, where she plays with the interface between analogue and digital. In the last couple of years Widauer expanded her medias to painting and sculpture. Her works have recently been shown amongst other places at Kunsthaus Zurich, Museum Belvedere Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austrian Cultural Forum New York, SPSI Shanghai.

Cornelius Wildner (*1970) is a Vienna-based sound artist and music technologist. He deals with ephemeral sounds, field recordings, archiving, live performance, analog and digital synthesis. At the same time, he collaborates with artists from different genres.

About the Interviewer: Erka Shalari (*1988, Tirana) is a Vienna-based art author. She focuses on discovering unique artistic positions, unconventional exhibition spaces, and galleries that have deliberately broken new ground in their working methods. In this regard, she relies on unorthodox publishing practices, coupling these with a nonchalant manner of writing. The work oscillates between articles for magazines, exhibition texts and press releases.