In her class, Layan switched between Arabic and English, so while I don’t speak Arabic, I still managed to pick up a few things about Saudi Arabian culture and literature. I was intrigued by her, so later I searched online to find out more. And that’s how I came upon Mauzoun, Layan’s writing studio and publishing house in Jeddah. About a month later, we met on Zoom to talk about Mauzoun, publishing in Saudi, the rapport between art and literature and why her favourite Arabic word is a very distinctive piece of Saudi slang…

Season 1, Episode 2: An interview with Layan Abdul Shakoor, Saudi-Austrian founder of Mauzoun, a writing studio and publishing house.

An Paenhuysen: Mauzoun has a beautiful sound to it. What does it mean in English?

Layan Abdul Shakoor: Mauzoun is an Arabic word that roughly translates to “poetically balanced” in English. It derives from a renowned Arabic saying, equivalent to the English phrase “well said”. In Arabic, it is pronounced “Kalam Mauzoun” which means, “balanced words”. We use the adjective “mauzoun“ with the intention that all our works are equally poetically balanced.

In 2018, Mauzoun was founded, then in 2022, you started publishing books. How did that process evolve?

It is a fully bootstrapped company, meaning we don’t have any shareholders or investors at all. I am the only founder. Currently, we are looking to expand and we’re sort of exploring the idea of having investors who come from a very keen cultural background. I founded Mauzoun in early 2018. From day one, there was the vision of encompassing both writing and publishing. But the publishing aspect is very costly: printing, logistics, even the permits to publish. I wanted to build up towards that organically and gradually, to expand the team and the business in a way that was fully self-funded. We started first with the content writing and book commissions, because that was within reach. We have our in-house team of designers, writers, translators, and editors. As much as we work on our clients’ projects, creating art books for museums and cultural institutions, we also work on our own line of publishing books.

How did the idea come about to start a publishing house?

From a sense of frustration, essentially. Or, let’s say, love and frustration. It came about from an unwavering love for language – any language I know – but especially the Arabic language. It is one of the prominent languages in the world. It has over 340 million speakers. That is a lot of native speakers – and that’s not counting those who have learned Arabic as a second language. Given the fact that it’s such an important language with a strong international presence, when you take the number of Arab publications, whether books or even Wikipedia pages, websites that primarily offer content in Arabic, the general standard is very weak. Many blogs or books are incredibly filled with grammar and spelling mistakes! I know it is a difficult language, yes, but mastering it is not out of reach. I would apply the benchmark of the highly-edited English articles I was reading, when I read Arabic content. And then I was frustrated that the Arabic wasn’t edited to the same standard – that is why I founded Mauzoun.

Does that mean that many texts get translated from English?

Sometimes, yes. I was primarily concerned with two aspects: content that’s for daily use, like medical, art, or fashion articles. And then there are more literary texts. I find some of the newer [Arabic] novels are rather weak, compared to ones that were published in the 1950s and 1960s. The editing process has dwindled compared to how it used to be. Many novels are translated from English, a lot are written independently. They all share the common thread of being remarkably linguistically weak. Luckily, since 2018 there have been brands like ours who have championed the improvement of Arabic content.

Did you study literature?

I didn’t study literature nor publishing. I studied media and filmmaking with a minor in theatre. Initially I thought I wanted to get into the field of media. After working there for a while, my one true love is writing and literature, which has always been a passion of mine since I was very young. So I went back to the roots.

What is for you the beauty of the Arabic language?

My background is multicultural, being Saudi-Austrian. Usually, with people from my background, our parents gave us an international education. People who studied at international schools had an education that focused more on English than on Arabic. Growing up, although my command of Arabic was very strong, I learned more through English media, books, and language. But it was only after I graduated from university that I began to have this extreme yearning for Arabic – not just the language, but the culture itself.

Arabic is one of the oldest languages in the world, yet it is very hard to separate the language from its culture. To dive into the language, you must dive into the culture itself. I did read Arabic books previously, I listened to Arabic music, I watched Arabic movies and television, but a large part of my early twenties was about really diving full force into Arabic media, more than I ever did before. It was my way to get in touch with that aspect [of my heritage], while balancing the cosmopolitan background that I had, to make sure I ended up with an equal balance.

What is the literary scene like in Saudi? What are people interested in?

Saudis are really cool, and I really want the world to know that. They have unique interests. People in the West wouldn’t expect it, but Saudis are really into: to paint with a broad stroke, edgy topics. For example, they are into horror – a lot! You wouldn’t expect this, from the stereotypical lens people see us through.

Currently, some of the bestselling fiction in Saudi Arabia are horror novels by an author called Osama Al-Musallam. Magic realism and horror – they are hugely successful genres here.

Do you also want to promote Saudi literature internationally?

There have been plenty of brilliant Saudi authors over time, not just recently. I think it is a modern myth, especially in the Western world, that Saudi literature is only now reaching a peak. That is not true. We have had local television series, both fiction and comedy, since the 1980s. We had hugely successful novels, not only in Saudi Arabia but in the Arab world that were published in the 1980s. The best known is Ghazi AlGosaibi who passed away some twenty years ago. He is still one of the most beloved literary figures. I think he is an excellent example of top-tier Arabic language work in the sense of storytelling and mastery of language. Saudi has been in the creative scene for a long time – not only now when it’s in the international limelight.

Is there anything characteristic to Saudi – and is this tangible in the literature?

Saudi Arabia is renowned for its hospitality. Everybody who comes and visits Saudi will be invited into people’s homes. It can be overwhelming, especially for people who aren’t used to this. We take Arab hospitality and push it to the extreme! But I still have not seen a novel that elaborates on that, and I really wish to see that. I feel like that is such a strong characteristic of our society that everyone knows and celebrates. Also, what characterises modern Saudi novels is a sense of curiosity and fun. A lot of them will touch upon contemporary topics through a curious lens. I think that is very important. It creates more nuanced novels that dive into the work’s angles in much more meaningful and deeper ways. There have been a lot of novels like this recently.

Do you approach authors yourself?

Yes, we do. To answer this question, I first need to explain something about the Arab publishing scene. It is unique in two ways. First, I believe it is the only region that primarily follows the pay-to-publish model. An author must pay a fee upfront to get their book published. Without paying, you can’t publish your book. So here, very few publishing houses follow the international royalty-based model. But as far as we know, we are the first Arab publishing house to follow that model. We don’t charge our authors. Secondly, when it comes to the works we publish, we proactively search for authors. We choose the authors based on a lot of criteria – mainly the originality of the work, the quality, and how resonant we believe the work will be with the Arabic market. We have to do that because literary agents are very scarce in the Arab world. They do exist, but it is a very new concept, and it’s not yet fully there. We’d love to see that grow.

In my writing class at Ithra, the students were taken aback when I proposed writing poetry. They said poetry has a very special status in Saudi Arabia, only written by those who have expertise in language.

I would humbly both agree and disagree with what your students said. If we’re talking about the state of poetry today in the Arab world, then yes, what they said is completely true. Poetry is a highly prestigious art, particularly in the Peninsula. I wish you understood Arabic – if you knew what the poems said, you’d be amazed! In the Arab world, poetry is so prestigious that many royals partake personally in poetry competitions. High-profile politicians and princes will also write poetry. Poetry here can be very intense, passionate, and filled with love – whether it be for a sport, a spouse, or a child. It is written in a Shakespearean form, for the lack of a better comparison – very rhythmic and [the words are carefully] weighed.

The poet is expected to read their poem in a certain way, almost like a delicate dance, to showcase how strong their mastery of the Arabic language is, as well as the meaning and nuances in pronunciation. It is one of the many marvels of the Arabic language.

I would also disagree with the students and say that the Arabic language has millions of words in its vocabulary, and it is a highly malleable language. There are young poets in the scene now, who write in a more contemporary style. They play around with the language more, and while their use of language is completely linguistically correct, they’re more playful and experimental in form. I love to see that because it is long overdue. As much as I love and respect traditional forms of poetry, I believe it’s also time to complement that with a contemporary form. I would even go as far as to say that applies to music as well. A lot of pop music in the Gulf is actually written by poets. Yeah, it sounds like a poem with pop music!

Do you have any favourites?

My personal favourite would be anything by the Saudi singer Talal Maddah. The number one star in all the Gulf now is Abdulmajeed Abdullah. But I also feel that the Arabic music scene also needs experimental and contemporary musicians.

How do you feel about the visual aspect of book publishing?

People choose books by their cover; we can’t deny that. Generally speaking, Arab books have weak cover designs, especially compared to Japan, Korea, or the English-speaking world. One of our main missions is to create book covers that follow a very high international artistic standard. We want to slightly push the boundaries of design to a better standard. If we are all about improving the quality of translation, content, and editing, we also must have equal quality with the aesthetics.

I saw that Mauzoun did a call-out for graphic novels on social media.

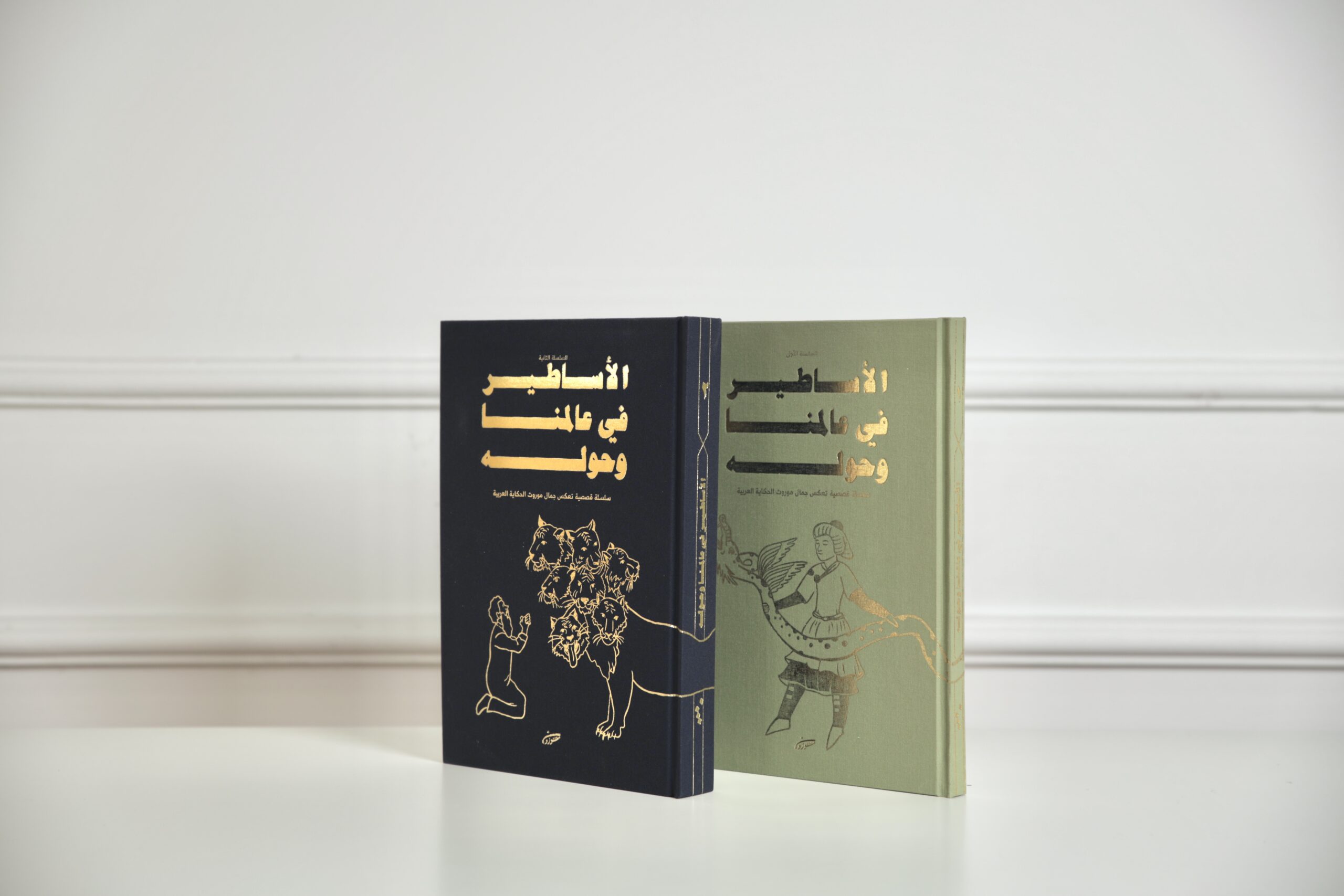

We do have graphic novels that we translated into Arabic, and now we seek to create and publish an original one. But our publishing department has three main lines. Firstly, novels. Then we have graphic novels – for example, we worked on and published the first Arabic translation of Bye Bye Babylon by Lebanese author and artist Lamia Ziadé. Then, our third and final range, coffee table books or art books, which are premium-quality. One example would be our The Myths in Our World & Around it series, a two-book series and there’s a box set as well. Surprisingly enough, it is our bestselling item, and a lot of people like to buy it as a gift.

Last year, in 2023, I visited the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah, which was so beautiful. The art world is booming in Saudi. How do you try to tap into that?

I couldn’t be happier about the booming art scene in Saudi. It’s very difficult to separate art from literature – they are cousins. Art is not just about the aesthetic, it’s not even about the works presented, it’s about the artists and their process. To see this celebrated is amazing. At the Islamic Arts Biennale, it was empowering to see Islamic arts and cultural heritage being celebrated in this region. My father’s family comes from Mecca, and Islamic art was a hidden treasure that Saudis knew, but the world didn’t know about. For it to be presented in both traditional and contemporary art forms was just lovely. We sold our books in the Biennale, which became by far one of our best-selling platforms. We believe that because our works align with the ethos of the Biennale. It is all about quality, about honoring authenticity, roots, and our culture in a contemporary way.

A last question: do you have a favourite word in Arabic?

I have a word actually! The word is مرة / marra. It has a funny story to it. In classical Arabic, it means “once”. I love this word because it is slang used only in Saudi. Here, it is used to say “absolutely” or “totally”. So when I say “marra …” it means “totally nice”. I love the word because Saudi has 13 different provinces, each with completely different cultures and accents, there is so much cultural diversity – but we all use the word marra! (Laughs)

Mauzoun – A writing studio and publishing house in Jeddah promoting Saudi

Arabian culture and literature – https://shop.mauzoun.com/.

About the Series: Curating, writing, and teaching brings An Paenhuysen to many places in the art world, from an artist studio in the 22-story tall Meritomi in Helsinki, a senseless residency in Milan, to the Kempinski hotel in Dhahran. Often, on those journeys, she meets people who are doing something interesting, different, and new. In this series, you will read about these encounters with artists, publishers, researchers, gallerists, and curators that gave off a sparkle so that An turned it into an interview.