For the second screening of Little Boy at Cinéma du Réel 2025, Benning was present in the theater to announce that there will be no Q&A after the session, that there is already a lot of „discourse“ in the film, and that he already had the opportunity to speak during the first screening. So, that will be it—too bad for the curious. The Reflet Médicis fades into darkness, and any anticipation of a post-screening discussion dissolves: Benning’s cinema itself, when donning the old garments of structuralist film, works just as much to annihilate any anticipation of the next shot. A year appears on the screen: a construction model is painstakingly painted while a popular song is played until its completion. Next shot. A fixed image of the painted model lingers as political speeches – Eisenhower’s Farewell speech, Chavez’s Commonwealth Club Address – take over the soundtrack. Once the speech is over, a new year appears, and Little Boy continues. The hands of the painter become increasingly older. No model city is built in the end.

The film’s temporality is that of its sounds. The builder’s gesture may be interrupted, but we will hear everything the masters of this „land of songs and speeches“ have to tell us—filtered through the Brechtian critical distance that, in Benning’s work, becomes a permanent suspicion toward what we hear. As a result, we immediately grasp both its artificiality and its danger—much like the makeshift predator that opens the film, a plastic dinosaur with a reconstructed roar. The selected addresses, alarming in their discussions of the climate crisis, failed revolutions, or the aftermath of post-Covid healthcare access, strike with their lack of solidarity with the visual elements. French audiences might push this independence to its breaking point by choosing to focus only on the subtitles scrolling beneath the screen, once they realize they are the only moving element to get its teeths – its eyes – into, thus removing themselves entirely from any contemplation of the models alone.

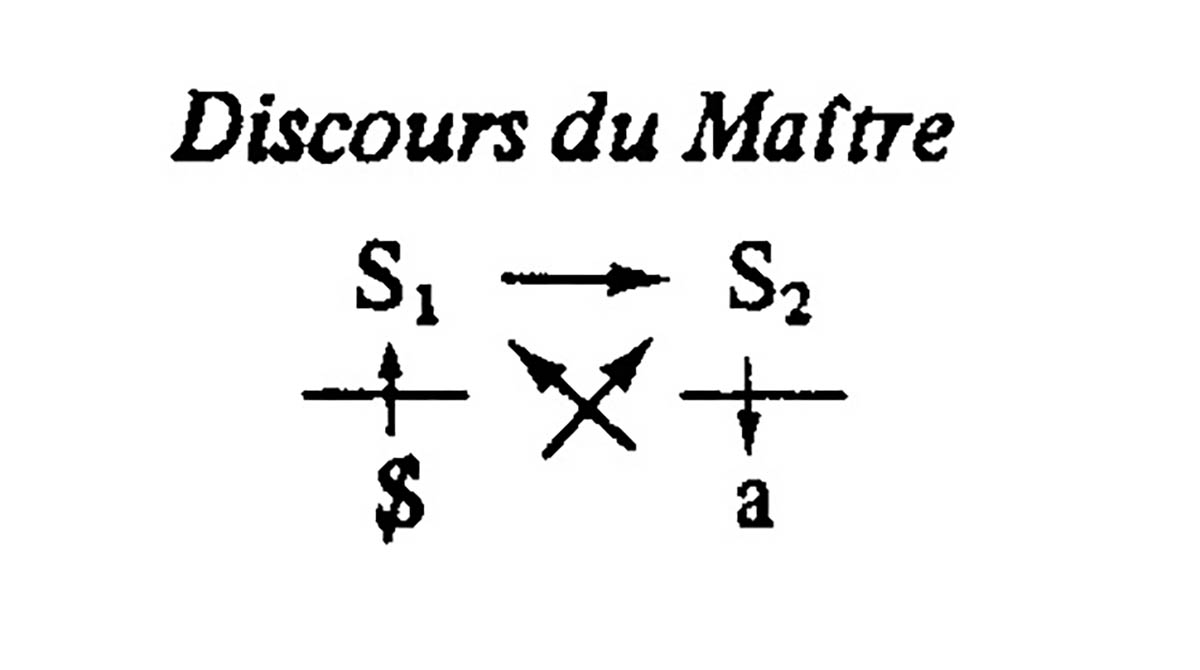

The circulation of speech mirrors the structure of a lacanian discourse of the master: a voice gives orders, imposes a framework, yet remains distanced from the truth of its own desire. The political speeches function as S1, issuing declarations, warnings, and ideological imperatives, yet they do not know what they want beyond ensuring that the discourse works (“un discours qui marche”) and perdure in time. Meanwhile, the visual—both childish and serious copies of industrial sites—occupies the place of S2, the repository of a silent, laboring knowledge, a material inscription that does not align with the verbal command. There is no direct relationship between the two; instead, a gap opens, revealing a fundamental disjunction between discourse and its supposed site of effectuation.

This gap does not feel merely like a structuralist tool of political critique but confirms a shift in Benning’s cinema, which is increasingly interested in the notion of eventfulness. The discursive events cited, although they seem almost to follow the various crises known in the USA in a rather scholastic manner, are nonetheless selected and collected by Benning. One cannot overlook the personal portrait crafted here: these are speeches that, in one way or another, have affected the director, and it is this affectation that distinguishes them from other speeches of the time. While the event remains opaque and impossible to grasp, it is also absolute, since it stands above the individual experiences of those who live it, and the event obliges the subject. Political speeches become personal events. Benning creates less of an auditory panorama of American politics than an event-based hermeneutics, an autobiography as an affected listener. As Badiou theorizes, the event is „supernumerary“—it exceeds the sum of its historical elements, resisting predetermined causalities and introducing a rupture. The event does not emerge from the preconditions of its site but instead forces an interpretation that retrospectively names and recognizes it. This paradox is central to Benning’s thought. If an event is always dependent on its situation, its essence remains indeterminate—any attempt to ascribe it to a given logic, a preexisting narrative, would dissolve its very nature.

By refusing the immediacy of shock or the clarity of narrative, Benning lays bare the very difficulty of defining what are the events that he proposes to us. Why this speech and not another ? As Claude Romano notes, there is no literary theory of the event—or rather, there is no literary theory whose originating site, whose epistemological stance, is the event as a founding concept, a transcendental condition of possibility from which literature might be thought. This paradox finds a rare cinematic transposition in Little Boy. The succession of political speeches represents a first definition of the event —temps comme succession—where historical moments are registered as a series of ruptures, one after the other, forming an intramundane chronology of political discourse, converging to a teleological End-of-History shared by the late David Lynch: the Bomb. Each speech belongs to a specific time, creating a linear progression of ideological statements that impose an implacable order of before and after. As Claude Romano analyse about this teleological conception of events: “The one who experiences the event is not engaged in his own selfhood in what „happens“ to him in this way: he is a „pure spectator,“ perhaps involved in the spectacle, maybe even struck by it, but not to the point of understanding himself through the event that thus happens to him.”

Yet, against this, Benning introduces another temporality—one that aligns with the second kind of event, l’événement comme substance qui demeure. The songs Benning uses are not contemporary to the political events they accompany; rather, they belong to Benning’s own experience of that year, forming a phenomenological and emotional recollection rather than a direct historical mapping. In 2010, he listened to Cat Power’s The Greatest (2006) while Hillary Clinton commented on the aftermath of 9/11. This musical and emotional coloring of the dominant discursive event anchors it in a political becoming that belongs to the citizen-director. Little Boy refuses to resolve the gap between the master’s imposed timeline and the fragmented recollections that resist its logic. The event, in its existential (and musical) dimension, is what Jean Greisch refers to as a „happy speech“. The joy and irrelevance of the musical interlude can be found in another ‘coloring’: on the dull model of a train station, two Keith Haring tags seem to taunt the dominant speech of the NO SMOKING sign. Behind the structural function, all the images of the film appear to be affected, stamped by personal and intimate history, making Little Boy a fully embraced apocryphal self-portrait of the American director.