I recently saw your documentary When Hades Bursts with Blooms, a collaboration with the Swedish Punk Icon Stry Terrarie Kanarie showing a journey through the beginning of punk to the post-punk era, landing at present day. What does punk music mean to you and your art and how much are you as an artist formed by that generation that you are a part of?

Of course, punk and post-punk has been a great source of inspiration in my art. Many in my generation have been inspired by Sex Pistols and Sid Vicious’ cover of “My Way”. In the 90s, as I started my career, there was a deliberating “fuck-you attitude”. Art history had previously been dominated by men. That radically changed in the 90s. Suddenly, you could be a woman and work in norm-critical ways. “Gender” and “identity” were central topics. During this period an idealism and a rebellious attitude emerged that was very similar to punk’s readiness to provoke. There was a feeling of newly achieved artistic freedom that widely questioned what works of art could look like and be. What one wanted was to break free and transgress boundaries – also literally. As a young female art student during the 80s, I wouldn’t dream of exhibiting internationally. But suddenly it was possible.

I also came to collaborate with people from the punk scene, as in the work you mention, When Hades Bursts in Blooms – a triptych I produced in close dialogue with punk icon Stry Terrarie Kanarie, artist Carin Carlsson and poet and writer Clemens Altgård.

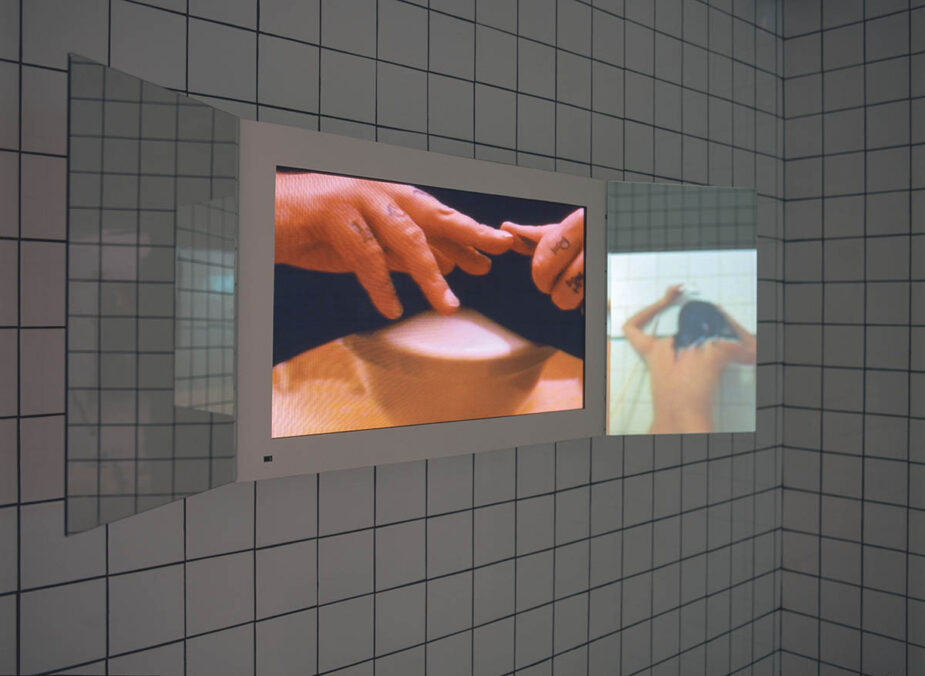

Lena Mattsson, When Hades Bursts with Blooms. Installation view Moderna Museet Malmö 2017, photo Lena Mattsson.

Lena Mattsson, When Hades Bursts with Blooms. Installation view Moderna Museet Malmö 2017, photo Lena Mattsson.

A lot of your art is video projected on different kinds of either objects or surfaces, like nature or buildings. What is for you the interesting correlation between a projected video image and the surface on which it is projected on and how do you choose the surface?

Very early on in my career, as video projection became possible, I was fascinated by the added and site-specific qualities of different surfaces and materials such as canvas, pillows, fortresses built of wooden barrels, gravestones, granite, tree trunks, cliffs – or later – entire islands and houses. I think this has to do with a certain obsession with the question of how to visualize life, or rather with the poetical and mythical energy developed as life, death and evil break through the neat fabric of the everyday. Finding the perfect site and the optimal surface for projection becomes paramount and is also a central sculptural element of my work, opening up a possibility to translate the personal into site-specific if not monumental works, so memorials of sorts.

So, stepping out of painting into reality has been a central ambition, as in the key work Breakfast for Everybody (Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, 1997–1998). Paraphrasing Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass), I combined video projection and performance.

I had breakfast together with my assistant, inviting visitors to take part, in this way also reversing the gender code of the original Scene. Recently, I have experimented with large-scale, outdoor video-mapped projections, playing also with scale, but also increasingly with what could be described as environmental narratives.

Engaging fundamental elements, such as water, enables me to address fundamental questions such as our attitude to nature or to that which connects us to previous generations, to our collective lives, actions, and memories.

Your impressive artistic career stretches through decades. Have you ever thought about giving up on art and what made you continue?

No, I will never stop creating art. I’ve experienced traumatizing events like death and disease. Life has never been easy. Art has given me a reason to keep on fighting and transform the negative to something positive. But maybe I could imagine other things to do, like researching on film and maybe pursue an academic career. One of my greatest passions in life is film and many of my works comment on film while trying out the borders of what film can be. In the magic world of art I can pose and highlight important issues, explore and push borders. I like to pose uncomfortable questions like for example gender or environmental issues in life and art. It’s beautiful to have art as a profession. My avenue for professional life was clear to me already when I was 15 and was a trainee at the Royal school of Art in Stockholm. Then I knew that I should spend my life as a free artist.

Lena Mattsson, Private Collection. Installation view Malmö Konsthall 2001-2002, photo Jan Uvelius.

Lena Mattsson, Private Collection. Installation view Malmö Konsthall 2001-2002, photo Jan Uvelius.

What inspires you in your artistic practice?

The basic material for me is life itself and its shortcomings. I think that revealing and visualizing complex questions is a characteristic of my art. I’m originally a painter and I still work with painting even though I’ve transformed it into animated film, video, photography, performance and sculpture. It is still my main material as an artist. I think that all of my works are self-experienced, poetic as well as general. I often work with people that I have a close and personal relation, and this too is an important driving force in my work. But apart from that I do most of the work myself; I’m the artist, director, script writer, makes sounds and edit my documentary films, sculptural video works and video mapped works etc. Since the 90s I have also worked as curator, which has been very inspiring. As curator I’ve tried to penetrate the surface in different ways, redirecting attention to the forgotten, to the margins of art and engaging audiences in that which emerge in the corners of the contemporary. The potential answers to the big questions always lie in the eye of the beholder.

What are you working on at the moment?

Right now, I’m preparing an exhibition “Unexpected Visit” that will be shown at The Art Gallery at Bohusläns Museum, Uddevalla, Sweden, opening 11.11.2023, and with a new site- specific work for the International Light Art Festival, Island of Light – Smögen, Sweden 2024. I recently published the book” Lena Mattsson – The Window Opens to the World” at Kerber Verlag in Berlin and I am now working on a continuation: a new book focusing on my larger projection mapping art works and monumental works in public space.

Lena Mattsson – www.lenamattsson.net, www.instagram.com/lenaismattsson/