Can you tell us a little bit about your background? You hold a bachelor’s degree in art history from the University of Oxford and a master’s degree in architectural history from the Bartlett School of Architecture. How did producing visual art and performing come into your life?

It’s hard for me to draw a line from this moment to where I am now. I don’t know what I took from that education into my work. I almost feel like the work would be the negative image or the reverse side of my studies. At Oxford, everyone was so genuinely, or maybe earnestly, interested in the pursuit of knowledge within the one specific field they’d signed themselves up for. But this pursuit of knowledge also led to a culture of hoarding. Hiding library books, refusing to share notes from lectures, and maintaining tight social circles according to which schools people went to. It’s like Fred Moten and Stefano Harney say: the university is a place that prevents study. In London, this was a bit better, but not so much. Although the professors I worked with had a much expanded idea of architecture, which encompassed writing and performance and therefore made a lot of things possible, the perception of the institution was pretty much the same as in Oxford. We paid our £9,000 fees to the university every year; the broadest base of staff got paid very little; the executive positions received monstrous salaries; and there wasn’t much anyone could or would do about it. It was a totally normalized hierarchy with a hierarchical norm. There was a pretty absurd time during my Master’s when members of the University and College Union were striking and we students had to decide whether we went to lectures by staff who were crossing the picket lines to give them. I honestly can’t remember, but I can very well imagine that I, thoroughly indoctrinated in this British neoliberal thinking about the essential purchasability of education, did go to those lectures during the strikes. Meanwhile, real conversations about the students’ and staff’s relationships to the institution were taking place outside during alternative teach-outs. And I wasn’t there! I wanted and needed my grades because I was paying over £10,000 of my own money for that degree. But also because I didn’t know anything about labor organization, solidarity, or workers’ movements because none of these things were ever featured in the curricula of art or architectural history programs. Just as colonial history barely registered at Oxford, it was the very English history that displaced my Indian family and then brought them over to the UK to work menial jobs in factories. These are, of course, histories that show up in art and architecture too, so there’s really no excuse. Anyway, I started producing visual art and performances when I realized that there were so many gaps in the “knowledge” I was supposed to have gained through study. The point was not to fill these gaps with some supplementary, positivistic, though equally inadequate knowledge, but to consider, tease, and probe these gaps and their relation to other aims that interest me more than knowledge: flourishing, understanding, love, and joy, to name but a few.

How do you balance your work as both a writer and an artist? Do you separate those two „worlds“? How do the two disciplines influence each other in your practice, and how different or similar do you find them?

I’m very fortunate to have opportunities to write and to make exhibitions, which are quite distinct practices. The balance would come from doing everything I want to do and saying no to the things I don’t want to do. But obviously there are times when this balance tips, and then everything kind of bleeds. It’s not always a bad thing; sometimes the messiness disrupts what is otherwise a fairly regimented working practice.

I started writing with a sense of purpose in architectural contexts, though I don’t really do this anymore. Funnily enough, there are now more architectural influences in my exhibitions and installations. So, I suppose I could say there’s quite a free osmosis between both practices, and fortunately for me, neither has anything especially disciplined or disciplinary about it. I think the one central and recurring preoccupation in my work as both a writer and an artist is language, especially what I would describe as the “constituting” aspect of language, i.e., language’s capacity to contain and shape, though also to institute and authorize.

Walk us through your process. How do you approach a new project or piece of writing? What role does experimentation play in your work, and how often does it pay off?|

There is little to no experimentation in my work. I don’t really have the time or resources for that. If I’m asked to provide a text or an artwork, I take the first idea that comes to me and see how I can bring it to fruition. It’s not a case of something “working” or not; it’s me who works, and the result is just a product of that labor. I try not to entertain the idea of progress or development in my work or to labor under an ideal. In writing, that just means sitting down and writing a text. I might read around a bit, make notes, or even map out a rough line of an argument. But it’s in the writing that something really happens. In exhibitions, on the other hand, the process is dependent upon the means available to me and how I can gather the materials, labor, and expertise to give the idea some kind of form. This might mean going to a professional who can produce something that I can’t, asking more knowledgeable friends and colleagues for their suggestions, or else accepting my own limitations (in terms of money, skills, and time) as the constituting factor in the work. It all gets made in the end, and, as far as I’m concerned, my designation as the author invokes my artistic and ethical responsibility for the product more than anything else.

How do you view the current state of the world of culture and art here in Vienna, especially regarding opportunities for emerging artists and writers?

It’s hard for me to talk about things in general terms. I think there are some very compelling artists in Vienna. It’s not especially diverse, though, which means there is often a tokenistic quality to the way in which People of Colour, as just one example, are assigned roles within the scene. Even if my work may sometimes be about cultural differences, it’s not usually about my particular diasporic background or experience. There’s a danger of pigeonholing vastly different artistic and subject positions into identity-based categories. When the discourse and understanding around certain social, cultural, or political issues fail to go beyond, say, nation-bound identifications and empty gestures of representation, this is not only a problem; it’s actually counterproductive to solidarity and mutual recognition.

To this, I would add (and it seems like a non-sequitur, but it’s not) that there is an astounding amount of public funding compared to somewhere like the UK. What I do appreciate about cultural production in Vienna is that there is quite an advanced discussion about the necessity of payment across different occupations, exemplified by fair pay guidelines that are at least nominally enforced by the cultural funding bodies and some institutions. Of course, it depends on the individuals and the work environment fostered within a project whether the number of hours budgeted actually equates to the number of hours worked. But here you have an Interessengemeinschaft to consult, and that’s not nothing. With this in mind, I would say that emerging artists and writers have the power to set the standards of practice for themselves and others. That doesn’t mean eschewing hard work, because I think the work is hard, though I really would like to see (self-) exploitation go out of style.

And going back to what I was saying before, the question of exploitation is also very closely linked to identification. To identify with a cultural group, for instance, I have to think about something Ghislaine Leung writes in Bosses, which I would paraphrase as: As long as we are being exploited, we are needed, wanted, and thus perpetuated. It’s those who are no longer even “worth” exploiting that we need to think about and worry about. And I think we have to consider the extent to which certain identity markers may inflect or even determine the work we do as individuals, especially if they’re being put to service elsewhere, at the expense of something that might resemble meaningful solidarity.

You have recently been nominated for the Belvedere Artist Award. What do you think this kind of opportunity brings in terms of new perspectives for your further development?

I honestly don’t think about my further development or see it as something I can steer in any particular direction. It was very nice and encouraging to be nominated; it came at a moment when I wasn’t really sure whether what I was doing had any resonances in Vienna. To have been nominated at all, especially with the other really wonderful artists, was in itself very uplifting.

Your solo show ECKDATEN at Brunette Coleman in London just ended; how would you describe it to people who didn’t have the opportunity to see it?

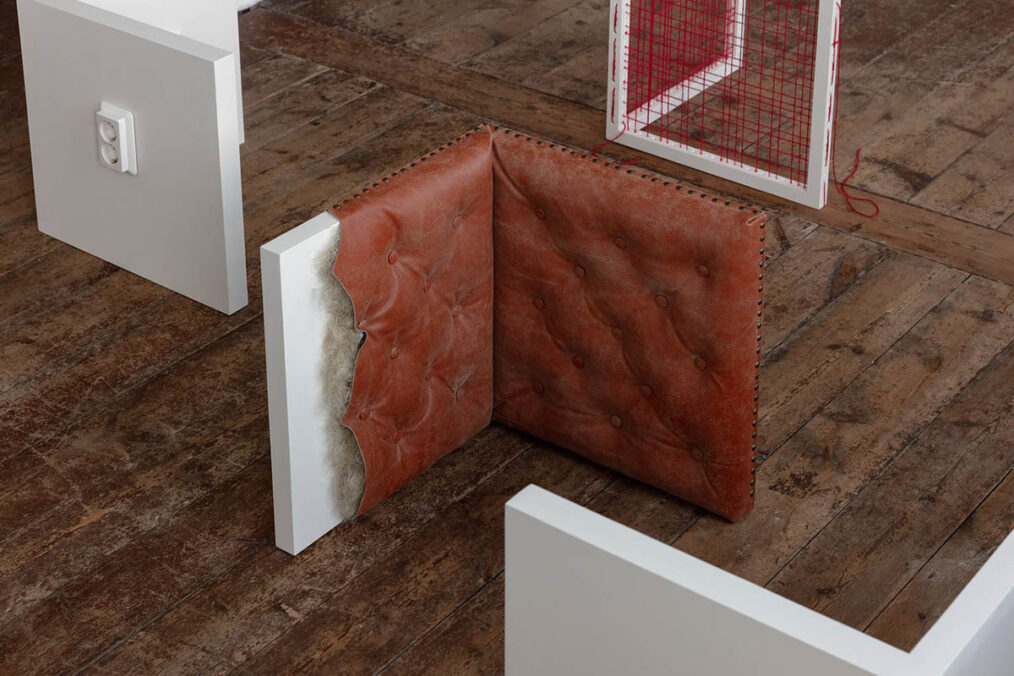

It’s a funny question because the show was made to exist as a counterpoint to a text that may or may not exist (yet). In that way, it remains a show that deals explicitly with text, though in a way that eludes this big thing called “Writing.” To describe the exhibition in words, then, is a bit beside the point for me. Then again, I could be a bit less obtuse and just say there were twelve corner pieces arranged within the room to map out a simple labyrinth. Each piece was differently adorned with materials generally applied to home building or making. I worked with a number of different craftspeople: a carpenter; a framer, who “happened to be” my partner; an upholsterer; a painter, who “happened to be” my best friend; a stucco-maker; and a bricklayer, who “happened to be” my father. I also made three drawings of maize, which were framed and hung in a corner in the gallery office. It was quite a tranquil show, a sort of minimalism in a minor key, which I suppose means a more ornate minimalism than the canon would otherwise have it.

You often play with phrases from foreign languages, so we often see German interwoven in your titles and concepts. You are also a translator; how many languages do you speak?

I speak German, English, and French too, though significantly less fluently. I am always looking for ways to complicate the relationship to text within my work, and languages offer a way of creating estrangement in some contexts. I’ve made work with Gurmu.khi, the Punjabi script, with only a very cursory knowledge of the language. Now I’m making works with French verb tables, which I studied quite voraciously as a teenager. I had 15 years of French lessons, and I grew up around Punjabi speakers, so the use of other languages in my work is never totally arbitrary or free of self-reference. But I don’t want to and can’t demonstrate a kind of sovereign power over the means within my grasp, be that text or language. I’m always turning these things over, trying to come to terms with all the things I don’t know, the words I can’t translate, and the textual traps I find it impossible to escape. Translation is a more banal process in which the result has to be operative. The nice thing about making art using different languages is that nothing has to be really functional in the end.

I remember your exhibition at Kevin Space in Vienna in 2021, particularly the works „Real objects, sensual qualities“ (2021, which consist of six beds for six books, but also „p. 111, […] bei stiller Lampe, fern dem Getöse der Alexanderschlacht, liest und wendet er die Blätter unserer alten Bücher“, which is a bookshelf corner from your latest solo show, ECKDATEN. I found the sculptural and conceptual qualities super exciting. Can you tell me more about the concepts behind it?

This is so nice! Thank you. I would say that I work with books as a „medium,“ with the whole multivalence of this word (as material, an intermediary, but also a clairvoyant) very much embraced through their different applications.

I like books’ dimensions and manual familiarity, their weight, and the way they conceal their contents and text, as long as they remain closed. Books are especially interesting to me because they promise escapism, not only in the sense of getting lost in a story but also in terms of social mobility. This was the point of tension in Real objects, sensual qualities: the image of the book in bed is taken directly from the Sikh temple, the Gurdwara, where the holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib, is treated with the same reverence as any other guru and therefore given a bed. The difference with my sculptures is that the books don’t get woken up in the morning and brought to bed at night, as they do in the daily Sikh ritual. They exist as inert markers of another cultural tradition, other philosophical traditions, which happen to be the ones that gradually brought me further and further away from my Sikh heritage.

I amass books that I don’t read; I haven’t read most of the ones in my installations. While I wouldn’t say I anthropomorphize books, I do think they are among the most prominent, recursive, and figurative elements in my work. They don’t represent the authors of the books but rather a bearer of something like thought, ideas, or maybe a narrative. In the work for ECKDATEN, I wanted the books to present a continuum of textuality, or intertextuality, which is why the immediately visible side of the work in the arrangement showed the edges of the bare pages, which all have a similar color palette, and not the spines.

I wanted to say, “Most of the time the books are just books, as far as I’m concerned,” but I do select each one carefully, so that would be a bit disingenuous. I guess they’re each cast to be part of a chorus; they have to sing the right tune to get the gig, right?

When it comes to exhibiting text in an art context, it can get complicated, and this is something I have been thinking about intensively over the last few years. How are you always finding new methods, and how are they evolving over the years?

I really don’t know how to answer this question. I think the fact that I work with text all the time—reading, writing, translating, editing, and proofreading—means that I encounter text in so many different contexts, which in turn inspire me and inform the work. It has changed insofar as I understand better that text has to have a very specific function in a sculpture, installation, or performance, and anything like ubiquitous text is, for me, really a no-go. That might mean foregoing written text altogether, as in the case of ECKDATEN. The text will just show up somewhere else, at a more appropriate time.

Are you a fast reader? Do you read multiple books at the same time, or one at a time? I would love to hear your reading recommendations. Is there a particular title that changed your view on life?

I’m not a fast reader at all. I do read multiple books at once, but I spend a lot of time with each of them individually. I used to bemoan this way of reading and how inefficient it was, but actually it enables a fairly deep engagement with, and a fulfilling experience of, a book. I think the last book I read that really impressed me was Diego Garcia by Natasha Soobramanien and Luke Williams, lent to me by my good friend and occasional collaborator, Tom Glencross. Recommending books is hard; reading is such a personal thing! I’m quite enjoying the New Narrative writers at the moment. There is a lot of poetry. Oh! I got issue 6 of the literary magazine fieldnotes, and it’s really, really excellent. Stephen Emmerson’s text, “Notes Towards a Resurrection”, especially. And not just because we’re both from Lincolnshire, England.

I don’t think any book changed my view on life; for that, I’d have to have had a view on life to start with.

Miriam Stoney – www.miriamstoney.com

Miriam Stoney (b. 1994, Scunthorpe, UK) is a writer, translator and artist based in Vienna, Austria. Recent exhibitions and performances include: Begegnungen / Encounters, Austrian Cultural Forum, London (2024), On the New, Belvedere 21, Vienna (2023), Just to let you know, Klosterruine Berlin/Kunstverein München (2023), Bergen Assembly, Bergen (2022), “nominiert…”, mumok Vienna (2022), Bad Words, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2022), Indebtedness, Kunstverein Kevin Space, Vienna (2021)