Which atmosphere is dominating in the exhibition space while the exhibition NATURE is on view?

What you could feel upon entering the room is this very intuitive atmosphere and composition that is very open and easy to read. You don’t feel the complexity of the process, but everything is light in the end, and this is the goal. It is a lot about letting go of power in the process of making the exhibition; there are deadlines to be met, and this collaboration on materializing my ideas is a big part of the final result.

Can you tell us how you got in contact with max goelitz gallery and how your cooperation came about?

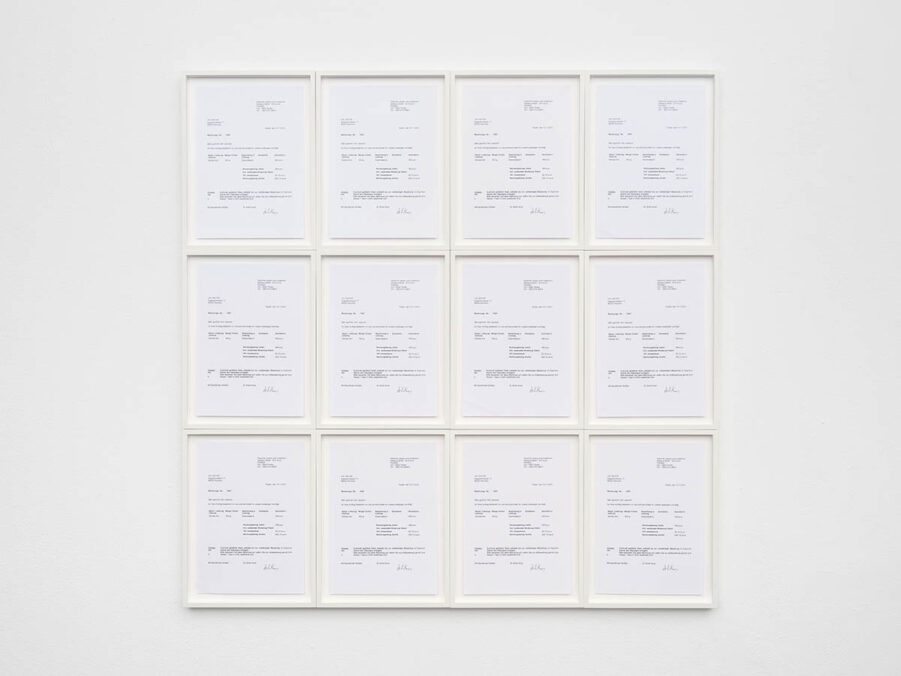

In the middle of the pandemic in Munich, there were a lot of restrictions on opening hours and allowing the public in the space of the gallery, but we did a first group show presenting the work of Michael Venezia and mine. The exhibition title was ROMs. This was my first cooperation with Max; he saw some correspondence between my work and the work of Venezia, as well as connections when it comes to the material we are using. In the 70s, Michael was spraying with aluminum in the form of a fluid spray, and what I did was printing with a meteorite, pulverized into pigment in a screen print technique. Max knows me from the work that was part of my master’s diploma show, and it is now exhibited as a part of the NATURE exhibition. The work’s name is SIKHOTE ALIN (2015), and it’s made out of 12-part silkscreens. The work depicts the invoice I received when ordering the meteorite. The invoice was printed until the meteorite dust was used up, resulting in a conceptual work of 12 sheets.

How is the process of producing your work looking? You are working with small ateliers and companies? How is this influencing the artwork?

Yes, this is a good part. I go to some workshops, small factories, and print shops, mostly in places that are not connected to creative work. I prefer to work with people who are new to it, and it is also an advantage for me if they say, “We never did that before.” to reach the goal and to get somewhere together with that small group of people. I love including people in my process; I think it is a lot about trust and sharing. It is about working with your hands and constantly approaching new ideas. There is a dialog in that process; this is what I think is most important.

Do you have small-scale models for the final sculptures we can see in the space? How long did it take to produce them?

I prefer to realize the final work as late as possible, and I enjoy the period while the piece is still a part of my imagination and can change shape. I didn’t have a small version of the sculptures, but I did have photos and a lot of 3D images, and in the program, I could enlarge, go in the shapes, and see them from every perspective, so I mostly work with that because the scale of the enlarge 3D view is much closer to the real dimension than a real small-scale model could be. Objects are printed in rows and in a certain pattern and grid, which by the way refers to the iron grids in my older works, and prints are done in parts, which together make the whole, which is why I chose this printing technique.

Pinocchio, a fictional character that has existed since the late 19th century, plays a main role in your solo exhibition, NATURE. You decided to use the representation of the Pinocchio character that physically captures the aesthetic of Disney Production. Why did you use this representation, among others?

Generally, the symbolism of the figure is very much connected to the idea of rebuilding a human, like the stories of Frankenstein, Golem, Metropolis, and Ghost in the Shell—the Japanese manga. Here we are very close to the idea of robots, and my reference to start this project was the topic of artificial intelligence and the fact that we are creating more and more robots that are used for industrial processes. You have for sure heard of robots that are working, for example, in the car industry. These robots are made out of just one arm and are reproductions of parts of the human anatomy. So we have this extreme between robots who are producing cars and are made out of metal and something like Frankenstein, and I think somewhere in the middle is Pinocchio, illustrated by Disney. With its joints resembling this robotic look but still being dressed in a particular way, I love the aesthetic of it, and I think this juxtaposition between these very sweet fingers and these strange elbows and mouths that give the robot references is quite interesting.

We see that Pinocchio is missing some parts, such as his eyes, and that his nose is in a way separated from him. Can you tell us more about these decisions?

Yeah, the nose is kind of deconstructed; it is missing. You can see some symbols in the exhibition that could represent a longer nose. I feel that the symbolism of the lying would somehow become so strong if the nose was together with other parts, and that was not the main idea. And I felt the nose was also a too-phallic symbol, so I decided on displacement.

What is interesting is how he is indeed a wooden doll, but you used materials describing the moment in technology right now. It is very interesting how the title of the exhibition is NATURE, and a lot of the elements are not coming from natural materials but from artificial ones.

This was also a choice. The traditional and older interpretations of Pinocchio are very folkloristic, and they are close to the idea of the marionette. It has something that is connected to the country. We all know about the genius sculpting in marble and this idea of the genius artist who is doing it to show how fantastic the human body is—in short, to celebrate the beauty and to show the perfection of nature. These ideas of harmonic nature, perfection, and symmetry are catholic ideas. The chaos, disharmony, or error is connected to evil, and it is perceived as something bad. And I think the story of Pinocchio and the fact that he is made by the old man and not the genius, without the technology and in this primitive way in his wooden workshop, and it has this nose that is growing. It is very interesting.

Lou Jaworski LA NOTTE VERTICAL REMIX, 2024 Courtesy of max goelitz Copyright of the artist Photo: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Installation view Lou Jaworski NATURE, 2024 Courtesy of max goelitz Copyright of the artist Photo: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Yes, it also has this magical aspect to it, as, for example, Frankenstein does. This parallel is interesting because Frankenstein is a novel that was written by a female writer, and there is speculation that she wrote it after losing her child, and this could be her way of bringing it back to life. Also right now in the cinematography, we have Poor Things, a novel by Alasdair Gray, which was made into the film, with similar topics about this superhuman idea or the perfect machine. I found it very poetic. Do you consider your works poetical next to the conceptual construct there is?

Yes, I do, and I feel I am trying to pose questions about trust and how much trust we want and are giving. Also, what is important is control. Especially when it comes to AI. How is the democracy dealing with it? I think this democratic system and its regulations, which we have here in Europe, are very linear and slow to adapt to new things, while I think that technologies and AI are not going linear but are exploding, and there I see the big gap between these two things. This is why, from one side, Pinocchio is chosen as a symbol for this whole situation, but also because of the idea of this figure created by humans that is not doing what the creator wanted, and there is this revolt against it.

Are you using AI to develop your idea? What is your connection with it?

Not at all. In the last ten years, there have been a lot of movements in art that remind me of fashion because they are quickly coming and going. Of course, institutions are interested in showing work that uses new technologies, and a lot of people are using them because they have “endless” possibilities. But I am not so sure about it.

I read a couple of days ago about the fact that AI cannot generate hands with human anatomy; there were always some glitches with it. When it comes to Disney, Pinocchio, and other characters, similar illustrations of hands are also always made out of four fingers to show that the characters are not humans but something else. Some glitches happen there as well.

Yes, it is very expressive, and I see that AI-generated pictures are indeed more on the expressionist side than on the hyper-realistic side; but also, in these pictures, you see this grotesque part we are afraid of, and it is hard to understand what we feel when seeing it. It is an uncomfortable situation, just as when we see puppets, marionettes, and robots, there is always some discomfort. It is unknown and fascinating; this fascination never stops. I feel there is now more focus on humans making themselves look like cyborgs than on trying to make robots look human. My idea would be to make very traditional clothes for the robots; this was the thing in the Baroque period with the first mechanics, but not anymore.

There are a lot of theories in philosophy but also art theory about the idea of the perfect machine, and I feel it is a lot about building something in search of your own identity.

I think why the Baroque people were dressing machines to look more like humans lay inside the core of the idea of humanity back then, it was much more poetic and much more romantic. We are now connected to the production process, with optimization referencing these strong capitalistic ideas. And now we are discovering our physical limitations and mental capacities. And we are lacking romantic structures. This is why I think we are trying to look like robots; it is just my hypothesis, but this is what I feel when I think about all of these processes. To go to Pinocchio, you see these robot parts, but on the other hand, you see this funny little costume of his, and it is bringing together both of these worlds.

You mentioned at the beginning that the exhibition is building this intuitive landscape in front of you when you are entering. I would love to ask about the prints on the walls—can they be perceived as a background? Can you tell us a bit more about the motives behind them and the techniques you used?

I knew that the sculptures in the room would be the main part of the exhibition; the idea was to place the images—“windows“—on the walls to open up the box of the gallery. I am very sensitive to architecture, and here I thought I wanted to build a horizon line on the walls consistent with the prints. And also to bring the idea of nature to the space, the sunset, and so on. The clouds are created in 3D, so you have 3D models printed on the surface and the ones printed as objects. The clouds are printed on the transparent metal mesh. It is a 3D fantasy.

What are you reading when you want to help research your project?

I love to read books in their original languages; I am reading in German, Italian, and Polish. Specifically for this exhibition, those two books are very influential: „Antikensehnsucht und Maschinenglauben. Die Geschichte der Kunstkammer und die Zukunft der Kunstgeschichte.“ by Horst Bredekamp.

And „Die Metamorphose der Frau. Weiblicher Schamanismus und Dichtung.“ by Wilhelm E. Mühlmann I just reread it after some time. This one was connected to the idea of the robot; in the last three centuries, it was much more often “that man created a man.“ I think it is a lot connected to the fear of the ideal man of the woman’s ability to create life, which defers to the female intuitive connection with nature. It is about production and creation. The book is documentation about the idea that the position of women in our culture was far more important, and this knowledge was eliminated by the Catholic Church and patriarchy for centuries, continually trying to make it disappear completely. As you can see, there are a lot of layers to my work. And there are a million references when talking about it.

Solo exhibition: Lou Jaworski NATURE

Exhibition duration: 9 February – 23 March 2024

On view: max goelitz gallery, Rudi-Dutschke-Strasse 26, 10969 Berlin, www.maxgoelitz.com

Lou Jaworski – www.loujaworski.com, www.instagram.com/lou_jaworski/, www.maxgoelitz.com/en/artists/51-lou-jaworski/