Recent exhibitions include „Critical Moments“ at Kannski Gallery in Reykjavik, where her works examined shifting meanings through objects, titles, and descriptions, and „The Content Shows“ series at Folkteatern in Gothenburg. She is currently completing her Diploma at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.

You were born in Sweden, studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna, and are currently studying in Vienna. How do these different locations and experiences impact your artistic practice?

Growing up between Sweden and Italy exposed me to contrasting cultural contexts. My first significant artistic encounter was as a child through my Sardinian relatives, who were masons. They built houses using local materials, often integrating found objects from nature into their architecture. They would ask, ‚Isn’t it beautiful?‘ and I would reply, ‚Yes.‘ This became my first dialogue about intuition and material sensitivity.

I often wonder how this conversation—rooted in labor and class—might have unfolded within an artistic institution, where such exchanges are valued as legitimate practice. When I later incorporated this thinking into my work as an art student, I found myself articulating what had previously been a wordless approach for my relatives. For them, however, intuition as a method had different consequences: it sometimes led to significant changes in construction, resulting in additional material costs not covered by their contracts or agreements, ultimately leading to conflicts.

In Sweden, I often felt that bodily experiences were dismissed in favor of rational thinking. Artists seemed expected to over-explain their work, ensuring the viewer wouldn’t have to engage in any discomfort or deep reflection. I often found myself craving a more intuitive and experimental space to develop my practice, which I eventually found at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. My time at Accademia di Belle Arti Bologna, on the other hand, revolved around classical materials and techniques, which ultimately led me to recognize my interest in everyday objects and materials.

You often work with spaghetti and/or heavy stones from stone walls. How did this combination come about? Was it influenced by the city of Bologna?

Because Bologna was unfamiliar to me and I didn’t yet know where to source materials, or maybe because I was hungry, I ended up in the pasta section of the supermarket across from the academy. Meanwhile, outside the stone workshop, I became more intrigued by the discarded fragments my colleagues had cut away than by the formal sculpting process itself. My works were shaped by my time in Bologna, but more as a response to the institution’s classical approach to materials and techniques than as a direct reflection of the city itself.

What role do materials play for you in your work?

Materials are a language to me, one that is more transcendent than spoken language. I speak Swedish, English, and Italian, but the exchange between physical materials in a work offers a much stronger bodily experience. Materiality simply exists. Spoken language is only used to describe.

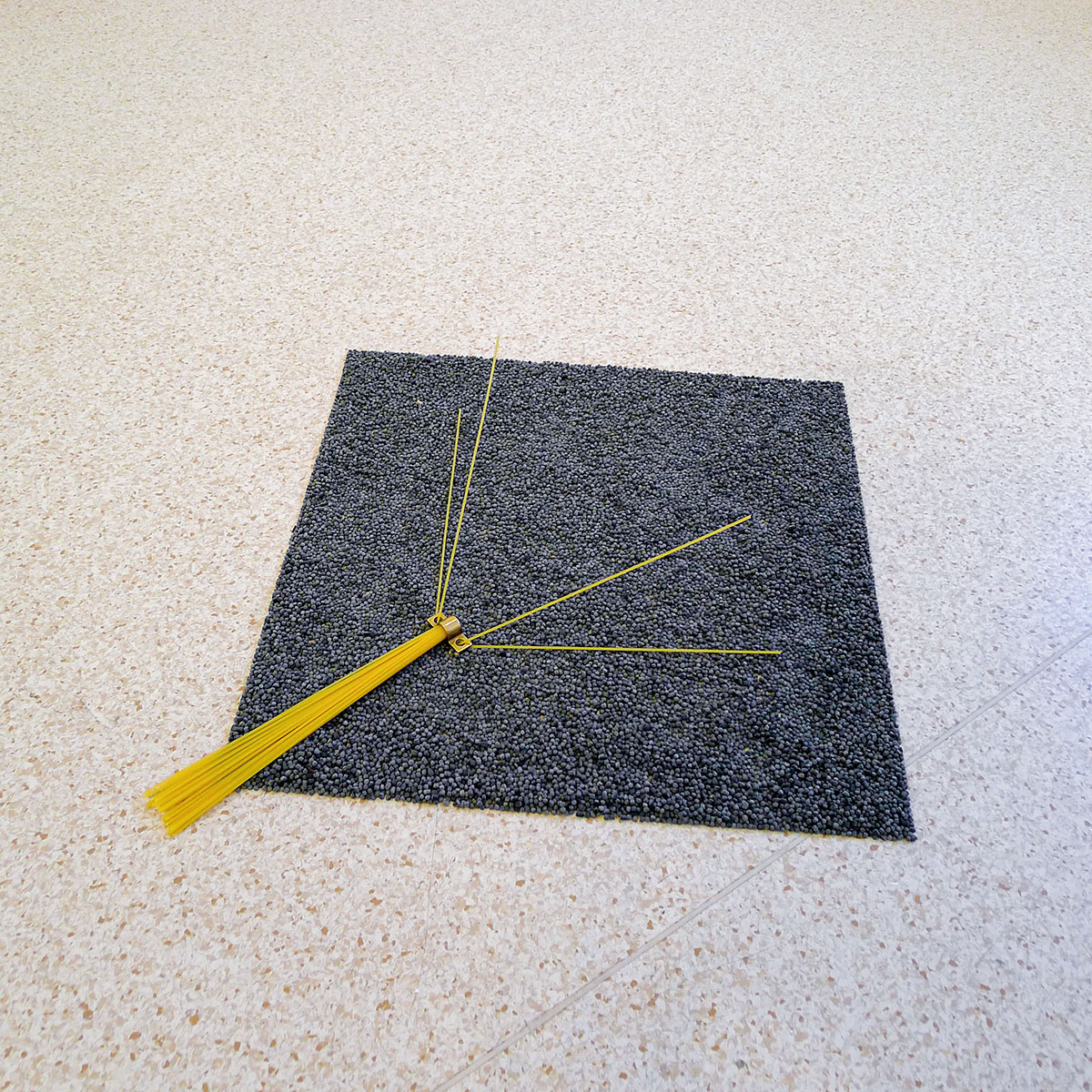

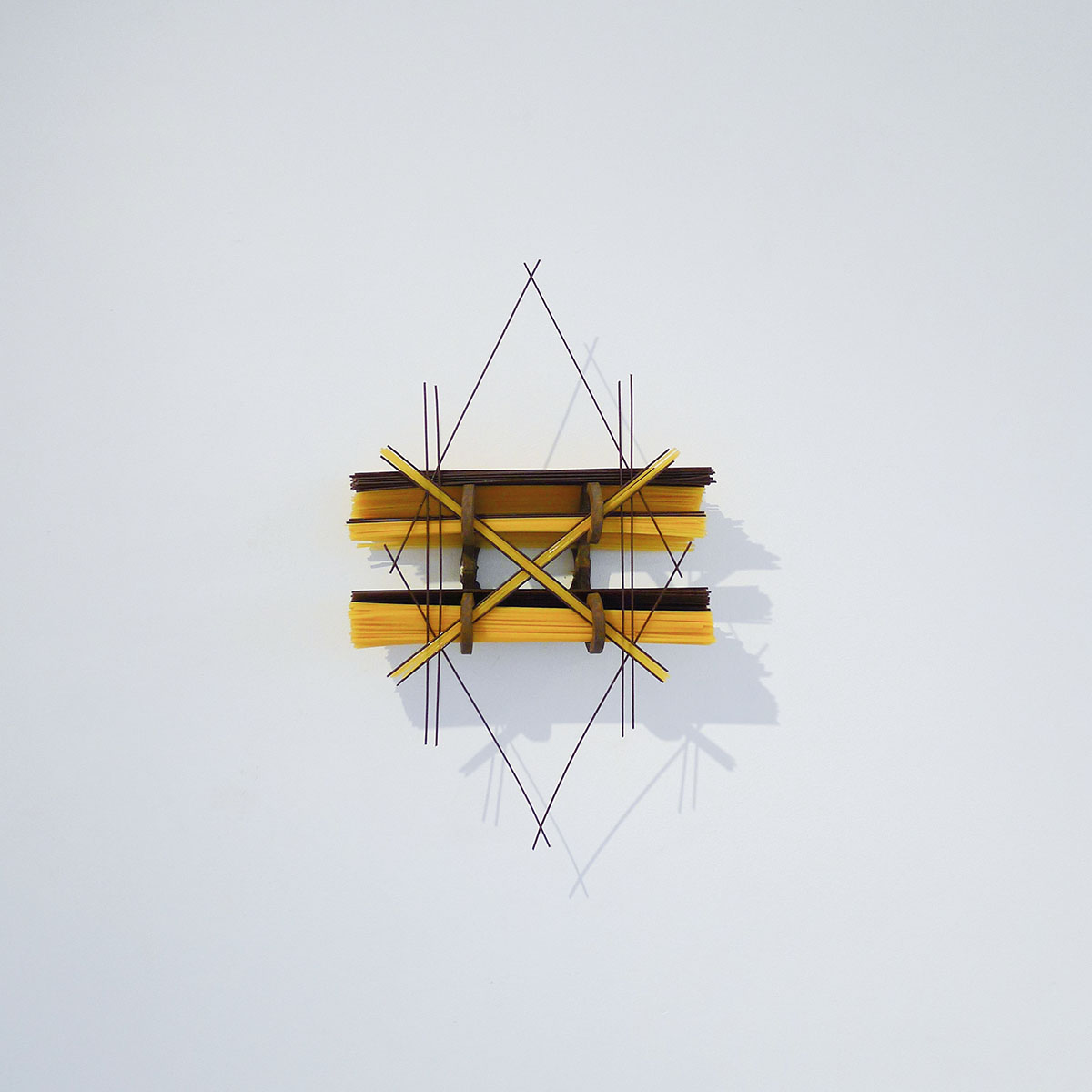

For me, much like in masonry, craft has always been about understanding the properties of materials—strength and weakness, balance, pressure, geometry, history—and combining them effectively, rather than transforming raw matter into symbolic or conceptual forms. I select metal objects based on their history, geometric shape, and ability to support other materials. Pasta carries great risk as it’s only strong when pressure and structure are perfectly balanced. Spaghetti bends in high humidity and breaks easily. Fregula is unevenly squared and responds to even the slightest vibration on the floor.

How do your works come into being? What is your process like?

At the moment, I prefer to work in the space where I source my materials. For the body of work featured here, I worked in my grandparents‘ house in Sardinia, collecting various metal objects. Some were purchased long ago, while others were crafted by my grandfather. The tile floor, laid by my grandmother’s brother, provided a blueprint for the square forms that reappear in my work.

I used to break objects, but now I only dismantle them if the construction allows it. I rearrange materials in multiple ways until I find a combination that excites me because it’s unexpected. I find it more successful to research through material, rather than the other way around.

Can you tell me more about your piece with the material description „metal object found at a house of a grandmother“?

I’m interested in how the meaning of objects, and by extension, the value of the artwork can shift depending on artistic intent, the materials themselves, and the viewer’s interpretation. For example, how do the material and its description influence the interpretation of my work? Based on this, could my work described as political in one context be interpreted as symbolic in another?

My works are often titled with descriptors like ‚Symbolic,‘ ‚Critical,‘ ‚Political,‘ or ‚Cultural.‘ These titles may appear alone or in combination. For instance, during the Critical Moments exhibition in September, which I co-presented with J. Pasila at Gallery Kannski, three pieces shared the same material description—’Metal object found at a grandmother’s house, durum wheat semolina, water, squid ink‘ yet each had its own title: ‚Symbolic,‘ ‚Critical,‘ and ‚Political.‘

What are you currently working on?

I’m focusing on my Diploma show at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, which will take place this summer. Afterward, I am excited to join the Nocefresca Residency in Milis, Sardinia, founded by Francesca Sassu.

Do you have any rituals?

I wake up around 8:00, have coffee and breakfast, and get dressed. I then take an hour-long walk to my studio— I enjoy how the same cityscape looks almost the same every day. At the studio, I work until lunch, then continue working until I feel done for the day. Afterward, I walk home and have dinner. I love a good repetition, whether it’s sticking to a schedule or eating the same thing over and over.

What significance does the exchange with other artists have in your life and creative process?

Some exchanges have been particularly significant to me, like the one I had with J. Pasila for Critical Moments. At that time, J. was based in Iceland, and I was in Italy. To plan the show effectively, we decided to meet weekly via video calls for the next three months. Despite not knowing each other and coming from different generations, and backgrounds, and working in different mediums, we managed to organize the entire exhibition without ever discussing real conditions or technical details. Instead, we planned the show through long conversations, diving deep into each other’s artistic thinking and working methods. Sometimes one of us would say, ‚It will fall into place when we meet in the space.‘ And it did.

This collaborative experience has been important to me, as it suggests that by deeply engaging with someone else’s way of thinking, discussions about technical aspects, which I find rather boring, can become irrelevant.

What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

That’s a funny question. Last year, I bought an old car from 1989 with my dad, and we’ve been repairing it together ever since. I find the mechanics quite intriguing, and I hope that one day I’ll be able to repair it on my own.

Isa Robertini – www.isarobertini.com, www.instagram.com/isarobertini/