What was the general atmosphere in postwar Vienna when the first Viennese Realists’ series of works—the graphic cycle „Soldatentreffen / Soldiers’ Reunion“—was created? How did the group exhibit and communicate with the audience?

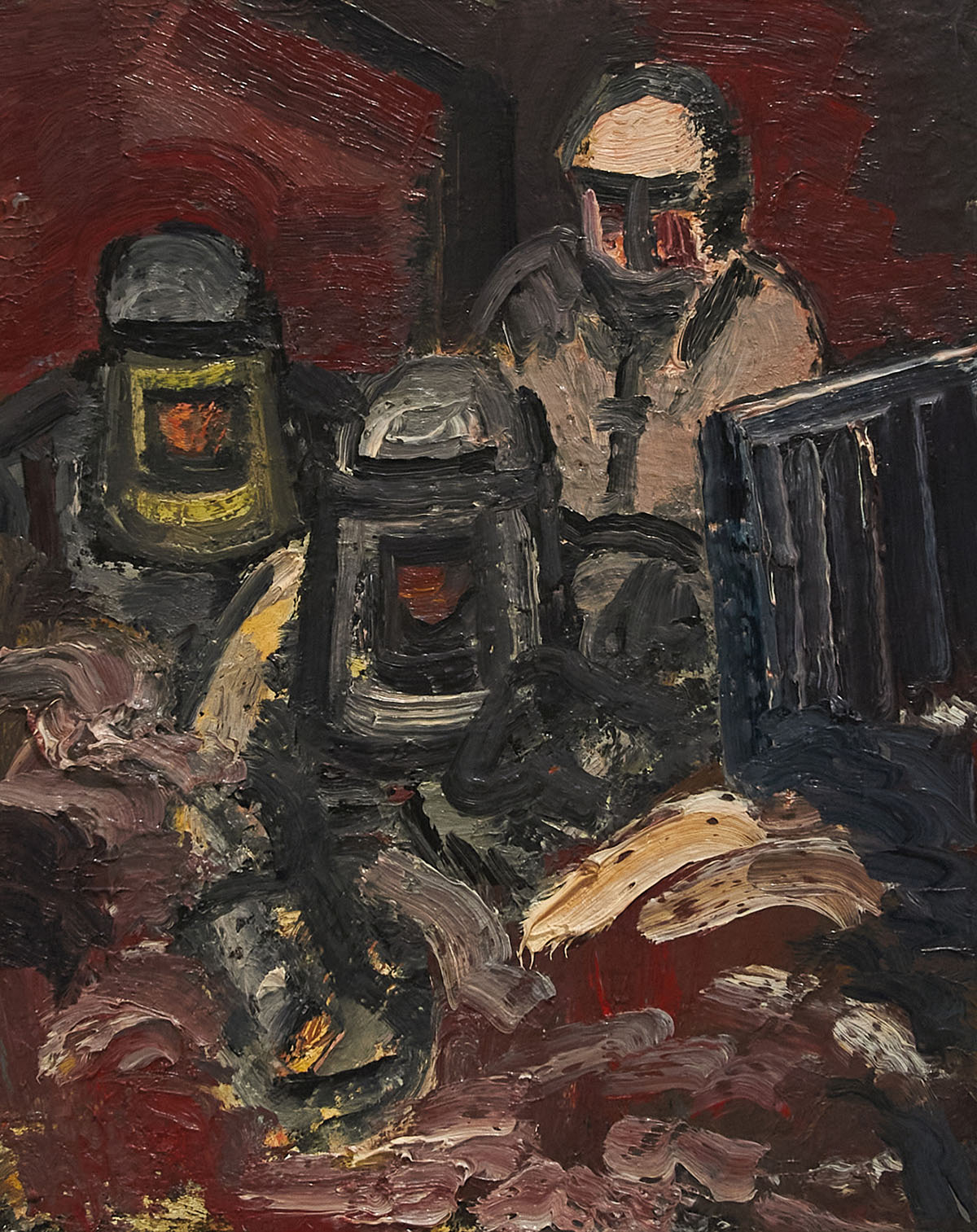

The situation in Vienna after World War II was very depressing. It was a moment of rural thinking in the city. There was little happening in terms of modernity or open-minded thought. National Socialists reappeared at public events, and former soldiers returned from imprisonment abroad, with some of them longing for the old days. In response to this situation, artists came together to form a group, deciding to take a stand against political and social evils. Let’s not forget that this movement started as early as 1952, which was quite early compared to other European countries.

At that time, the Council for Peace took place, involving 50 nations, and two Mexican artists received the Peace Prize. These artists visited Vienna, where they connected with the Viennese artists and discussed working toward political goals through art. The group operated a printmaking workshop called Taller Graphika Popular, producing prints with political content that our artists later adapted in their own practice. The technique—linoleum printing—was already widely known and relatively simple. It was decided to create a series of linoleum prints with social themes, opposing war, poverty, and capitalism, as most of these artists leaned politically left.

They produced the series „Soldatentreffen / Soldiers Reunion“ in an ironic manner. The edition was created six times, and the series currently in our collection, now on display in the exhibition, is the only complete set known worldwide. This is the first time it is being exhibited in Vienna.

Can you elaborate on the title of the exhibition and how it could be interpreted?

Realism has existed since antiquity and continues to evolve, manifesting in different styles. Rather than focusing on realism as a method of artistic production, we wanted to highlight the attitude that defined this specific moment in Vienna and its societal impact. Brigitte Borchhardt-Birbaumer and I based our curatorial decision on the concept of attitude in the sense of one’s position toward society, human living conditions, and the world around us.

How did you engage with the movement of Viennese Realism throughout your research and curatorial work?

Working with Viennese Realism was challenging because very little art historical work has been done on it. The exhibition space was designed to present both the beginning and the end of the movement right at the entrance. The work by Alfred Hrdlicka before 1988—“Model for the Monument at Albertinaplatz“—marks the movement’s conclusion. The main exhibition space showcases works primarily by the core group: Georg Eisler, Hans Escher, Alfred Hrdlicka, Fritz Martinz, Rudolf Schönwald, and Rudolf Schwaiger. In the outer exhibition space, we feature works by younger artists and more female artists, grouped into thematic chapters.

Additionally, Wien Museum undertook the restoration of Fritz Martinz’s painting Der Große Liebesgarten (1959–1960), which had previously been stored rolled up and was in very poor condition. The restoration process took a year, involving a group of conservators working in collaboration with students from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. We are delighted that this painting is now once again on public display after so many years.

I was surprised by the number of female artists included in the exhibition, considering that the period was not particularly known for well-recognized women artists and it was, in general, a very bad period for being a woman.

This was a crucial aspect for us. At the start of our research, we identified six male artists as the movement’s core. However, we were also aware that the position of female artists at the time was very difficult. We therefore actively searched for other artists who shared the same commitment to making art for the betterment of society, and we made several important discoveries. It is common to find female artists who produced remarkable work but were not nearly as recognized as their male counterparts. For example, Gerda Fassel was also a professor at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and a successful artist.

How would you compare or contrast the Viennese Realist movement with Viennese Actionism, which also engaged with Austria’s post-war period through the themes of the body and post-traumatic experience?

Adolf Frohner was one of the founders of Viennese Actionism, but by the mid-1960s, he had decided to leave the group and become a realist artist. This is the most direct connection between the two movements. I believe that the Viennese Realists were deeply convinced of the necessity of engaging with society. For them, this was the core principle: to be effective and to improve conditions through their art. In contrast, the Viennese Actionists were not as accepted by society at the time of their work. They produced great work, but it was communicating with rather a small group of people.

Existentialism and humanism were philosophical and psychological movements growing in France during this period—particularly through the works of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. Can you draw any parallels between these movements and what was happening in Vienna at the time?

Yes, existentialism and humanism were very much present, along with student protests, the sexual revolution, and the rise of feminism next to others. These ideas were in the air, and I am sure they influenced artists in Vienna, whether consciously or unconsciously. During the 1970s, we also had the Kreisky era in Austria, which brought about significant modernization and social progress. This broader cultural and political shift played an important role in shaping artistic expression at the time.

Could you imagine expanding the exhibition to include works by contemporary artists who share a similar drive for social impact?

The issues highlighted by the Viennese Realists have not been fully resolved—far from it. Many of those problems persist, alongside new ones. There is still much that art can contribute to society, and I fully expect a movement like this to emerge again.

Art is about thinking critically about society and communicating with it in a profound and grounded way. This kind of art is essential, especially in today’s world.

Exhibition: Truth as Attitude: Viennese Realism after 1950

Curators: Berthold Ecker, Brigitte Borchhardt-Birbaumer

Exhibition duration: March 20 – August 17, 2025

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday 10 am–6 pm

More about the exhibition: www.wienmuseum.at

Artists: Luis Arenal, Christy Astuy, Lieselott Beschorner, Lena Brauer, Georg Eisler, Hans Escher, Gerda Fassel, Erna Frank, Adolf Frohner, Günther Heinz, Wilhelm Helfert, Wolfgang Herzig, Alfred Hrdlicka, Moni K. Huber, Johanna Kandl, Alfred Karger, Anneliese Karger, Josef Kern, Dieter Kleinpeter, Renate Kordon, Günter Krasser, Fritz Martinz, Mara Mattuschka, Thomas Nemec, Florentina Pakosta, Richard Pechoc, Glauco Rodrigues, Rudolf Schönwald, Rudolf Schwaiger, Carlos Scliar, Herbert Traub, Monika Verhoeven, Rainer Wölzl, Franz Zadrazil, Arno Zambanini

Address and contact:

Wien Museum MUSA

Felderstraße 6–8, 1010 Vienna

www.wienmuseum.at

Berthold Ecker was born in 1961 in Linz. Student of art history and cultural anthropology at the University of Vienna. At the Visual Arts Division in the Department of Cultural Affairs of the City of Vienna since 1991; head of the division from 2003 until 2017. Member of the Board for “Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Wien” (Public Art Vienna) from 2004 until 2017. In 2003/04, founder (with Bernhard Denscher) of the Month of Photography Vienna and the European Month of Photography. From 2007 to 2017, Director of the musa Museum Startgalerie Artothek, the Department of Cultural Affairs’ exhibition space for contemporary art. Curator of the Wien Museum since 2018; curatorial responsibilities: painting, graphic art, and sculpture since 1960; new media; art photography in the present; musa. www.instagram.com/bertholdecker_/