This exhibition focuses on integrating digital technologies with the tactile aspects of painting, presenting a series of works that challenge and extend the boundaries of artistic creation. Andr’s approach, characterised by the synergy between algorithmic computation and manual intervention, offers a novel perspective on the possibilities of contemporary art.

Can you tell us about your background and how it has influenced your approach to painting?I grew up in a small village with very religious parents, and I had no exposure to or access to art whatsoever. Still, as a child, I found myself constantly drawing, and at the same time, I developed a fascination with computers, coding, and digital technology.I clearly recall the day in 1984 when I was six years old, and my father brought home our first computer. The visual element of computing captivated me, watching my dad code his own computer games. As screens evolved from displaying just two colours to 256 hues in the late ’80s—and eventually millions—I was entranced by the expanding visual potential. This early exposure opened my eyes to the limitless creative possibilities within the digital realm.

In my mid-teens, the grip of religion on my life lost its hold on me, leaving me searching for something else to ground me—something that could offer the sense of truth and stability I once found in the idea of God. It was during this period of uncertainty that I found painting. To me, painting felt like a new language, one that might offer answers. I held a somewhat naive belief that by capturing the world on canvas, I might somehow come to understand it. Painting became a pursuit of truth and an attempt to make sense.

I was blindly trying to find my way without any guidance, and my path began somewhat inauspiciously. At 18, I enrolled in the Florence Academy of Art in Florence, Italy, to study 19th-century French academic drawing and painting techniques. The Academy’s emphasis on the Sight-Size method—a meticulous approach focused on accurately capturing reality—required us to spend months perfecting individual drawings to achieve a „true likeness“ of a plaster cast, a nude, or a still life. While this intensive training sharpened my observational skills, I felt very constrained by its dogmatic approach, presented as an unquestionable truth that seemed to drain the vibrancy and spontaneity from painting.

What prompted you to move away from traditional painting methods after this period?

I reached a turning point where I began to question the core of my practice. The long-held belief that the goal of painting was to replicate reality no longer resonated with me. I wanted to break free from the constraints of precise reproduction and explore new realms where art could transcend mere representation. After my time in Italy, I was granted the opportunity to paint for six months in Edvard Munch’s former studio at Ekely in Oslo, Norway. This experience led to a period of experimentation with painting techniques. I used an early version of Photoshop to digitally cut and merge photographs of models into single composite images, which I then painted—shifting my focus beyond mere likeness to explore new creative possibilities. This experimentation continued when I moved to London to attend the Slade in 2002. Eventually, I stopped painting entirely on my 30th birthday. I wanted to free myself from everything traditionally associated with painting—composition, colour mixing, and, above all, the idea of truth in likeness—and instead, approach an image as something closer to an unfixed meaning, something that embodied a form of movement. This longing led me to put down the brush for the next 10 years, and I started to make text-based art, using black and white letters to form imagery.

I turned to computers to make my art digitally and used machines to make my art tangible by cutting out letters and words, allowing them to shift from signifiers to images and back again. I viewed the components of language as a visual medium, designing compositions where meaning was fluid and open to interpretation. By placing opposing words like „true“ and „false“ on top of each other, more as a pattern or an image than a word that signifies, I aimed to dismantle fixed meanings and examine the fluidity of perception.

After focusing on text-based art for ten years, what drew you back to painting, and how did your approach evolve?

I found great intellectual pleasure in exploring the drifting between image and words, but after 10 years, I longed for the tactile experience of painting—the physical act of applying paint to a canvas and the materiality of paint, along with the movement of the body in the process. I increasingly saw the potential in technology and realised that it could be utilised to push painting in new directions—closer to what, I felt, was connected to myself, but also our daily experience of life in our digital world.

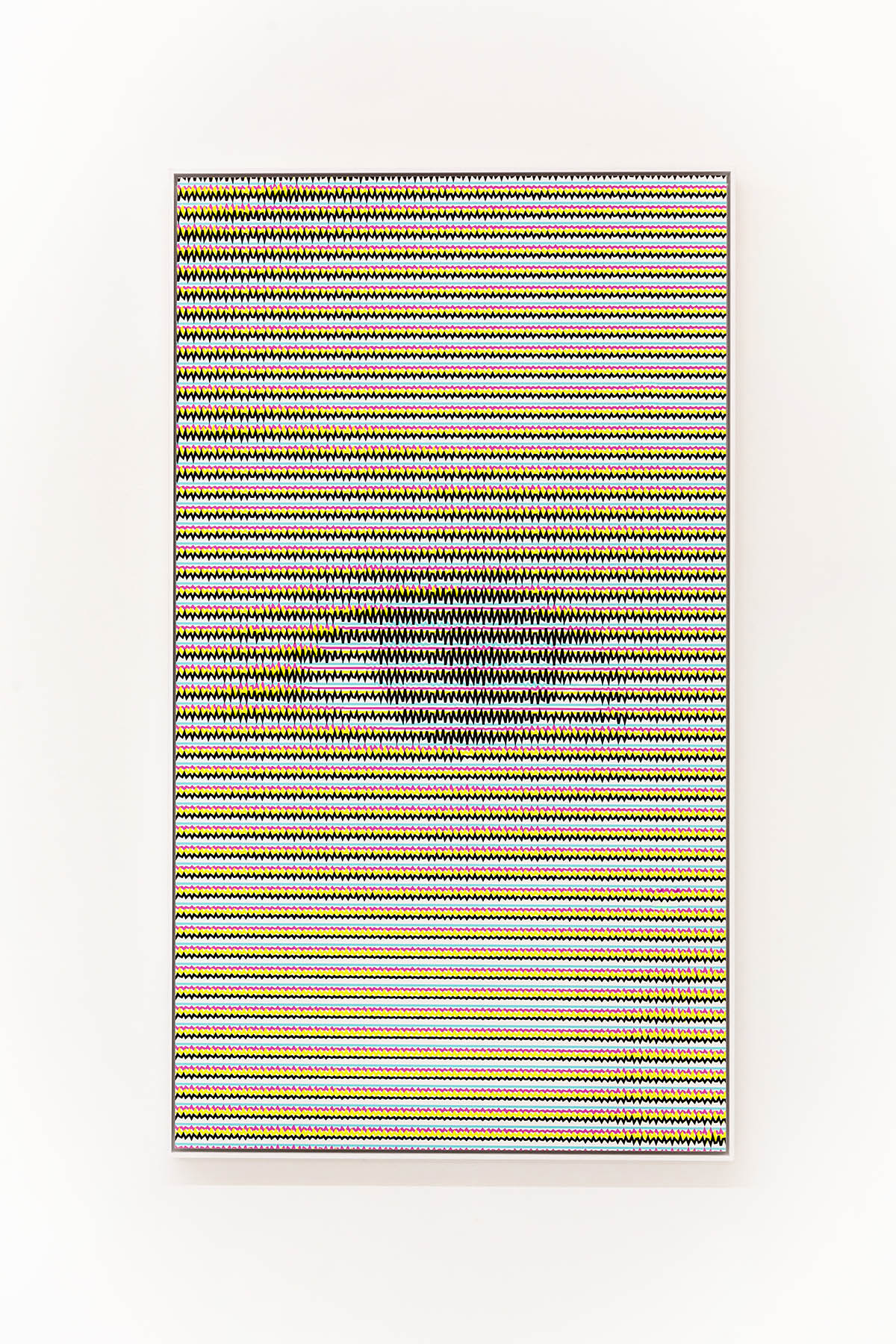

During my PhD at the Royal College of Art, I created what I refer to as the System of Emergent Touch (SET).SET is an algorithmic framework that analyses digital images and employs mathematical algorithms to determine the premixing and placement of paint on the canvas. However, the vital aspect lies in the touch itself. While the algorithm offers guidance, it’s my hand—the pressure, movement, and subtle nuances—that breathes life into the painting. This method has provided me with a sense of freedom, enabling me to collaborate with an algorithm that handles the traditional elements of painting while I focus solely on the tactile experience—the act of ‘touching.’ The tactile aspect introduces an element of unpredictability and emotion that algorithms, at this stage, seem unable to replicate.

Can you delve deeper into how SET explores the relationship between humans and algorithms in your work?

SET connects digital computation with the tangible nature of painting. The system operates not with the algorithm performing X and me executing Y separately; rather, the artwork results from our co-working. The algorithm lays down a structural base—calculating colour mixtures, placements, and composition—but it isn’t a rigid script. There is room for interpretation and spontaneity, allowing the human touch to come alive, with the code itself evolving throughout the painting process.

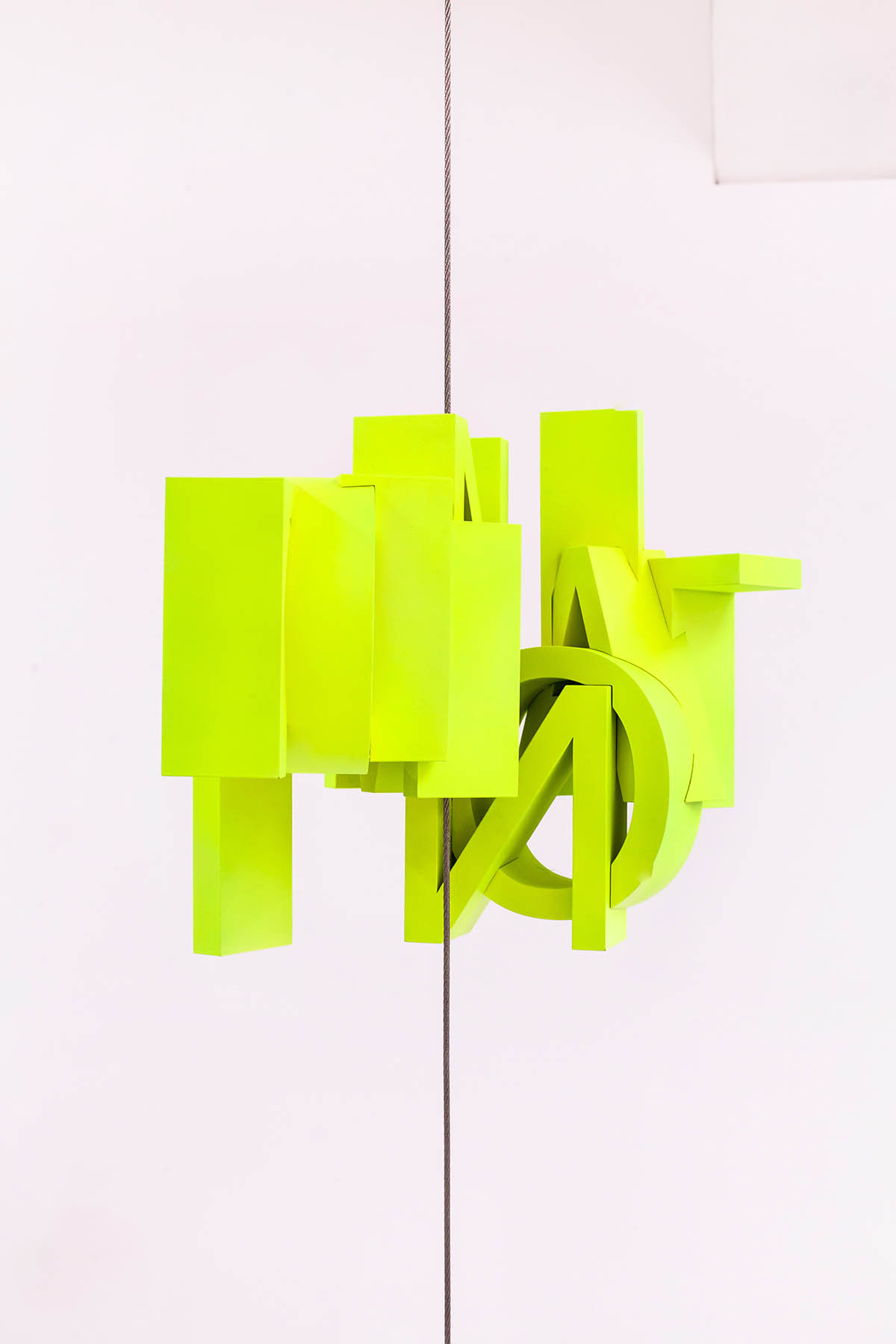

When not using SET, I frequently start from the binary code or a 3D photorealistic rendering, allowing a physical image or sculptural entity to emerge using 3D printing and other digital technologies. Despite this technological involvement, each piece retains a handmade quality, with every surface crafted by hand. I strive to create objects or images that exist in a state of flux, unfixed and shifting between digital and analogue processes—a co-working interplay.

How does this collaborative process impact your understanding of authorship and creativity in art?

This process shifts the artist’s position from that of a singular creator to a collaborative co-creator. It questions traditional notions of authorship and opens up new paths for artistic expression. By distributing agency between humans and algorithms, we embrace a post-human view of creativity—one that sees it as interconnected and emergent. This process also encourages us to rethink the meaning of art. Does it lie in the initial idea, the execution, the interplay among elements, or perhaps in the novel qualities that emerge through collaboration? The unpredictable nature and emergent outcomes of this collaborative process enhance the depth and intricacy of the artwork. This co-working resulted in an emergent artwork that neither the algorithm nor I could have created alone.

In an era where AI and automation are often seen as threats to human creativity, how does your work respond to these concerns?

I perceive technology as an opportunity rather than a threat, broadening the possibilities for creativity. It’s important to remember that AI lacks consciousness and free will; it cannot make any decisions beyond what it’s programmed to do. AI is simply a form of automation, and in this sense, the technology isn’t as novel as we might assume. The dystopian views on AI often arise from the belief that it will overpower human contributions. My approach aims to establish a co-evolution method, fostering a symbiotic collaboration between humans and machines.

By underscoring the unique significance of human touch, I draw attention to creative elements that machines are incapable of reproducing. Additionally, I challenge the traditional interpretation of ‚touch,‘ shifting away from a solely human-centred perspective. In this exploration, touch transforms into a broader concept, transcending mere human interaction and embracing the connections between humans and AI. Together, we can explore things we cannot access or do independently.

Exhibition: TAKT by Be Andr

Is on view until February 1st, 2025, at HALLE13

Opening Hours: Thursday & Friday 2-6 pm, Saturday 12-4 pm

Address and contact:

HALLE13

Elisabethstrasse 13, 1010 Vienna

hallo@halle13.net

www.halle13.net

Be Andr – www.beandr.com, www.instagram.com/be_andr/