How are you feeling now that the exhibition has been open and running for a couple of months? How was the overall process for you?

It was a great experience for me. This was the first time I had an exhibition in an institution, and I also had the opportunity to exhibit multiple projects in the same space, which was a good chance to gain a broader perspective on my work up un- til now. It allowed me to reflect on my practice and shape future plans.

The work for which you won the prize is a two-part installation: HIJRA–Queering Borders and DUKHANIA–The Protesting Archive, which are exhibited alongside your other works. Can you describe the connection between them?

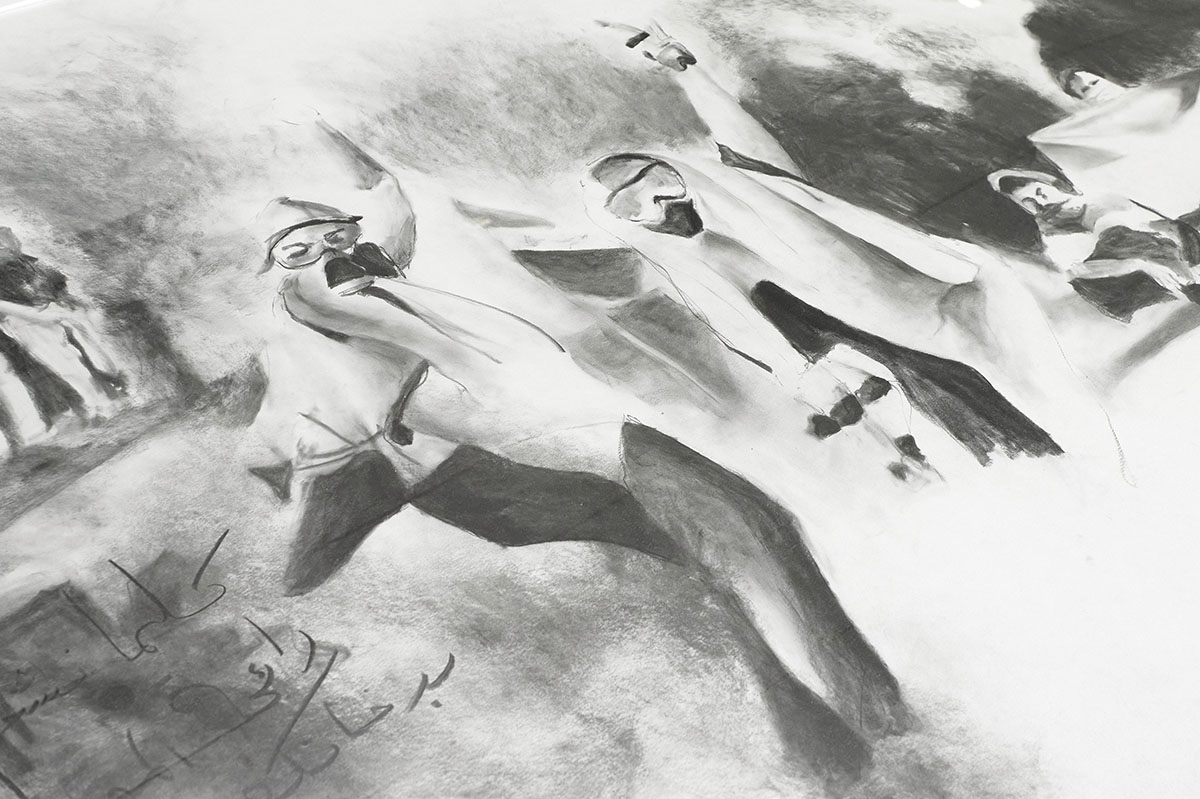

Yes, I was awarded for my two-part installation, HIJRA–Queering Borders and DUKHANIA–The Protesting Archive. These works draw inspiration from my experiences as a refugee and my activism. The ample exhibition space at Kunsthalle Karlsplatz allowed me to present a substantial body of work and establish meaningful connections between the pieces. My work is a way to create a collective moment of witnessing the stories of those who have been overlooked in the West while also questioning how such narratives should be considered.

My practice is rooted in documentation, whether personal stories or political themes related to my home country.

How important is it for you that visitors understand the context of your works and your activist voice? What if they simply engage with the formal aspects of your work?

It’s very clear for me: if I’m not making political work, then why am I making art? But this is just my perspective. Art is a tool for me–a medium to share my thoughts. I’m not someone who talks a lot; I’m a very calm person, but my work gives me the space to express my voice. So, I need to put it out there. However, I don’t mind if people simply look at the paintings without immediately engaging with the context or discourse behind them.

If I’m not making political work, then why am I making art?

Activist-driven artworks are often „loud“ in their formal sense, but your works convey their message differently. Can you elaborate on this?

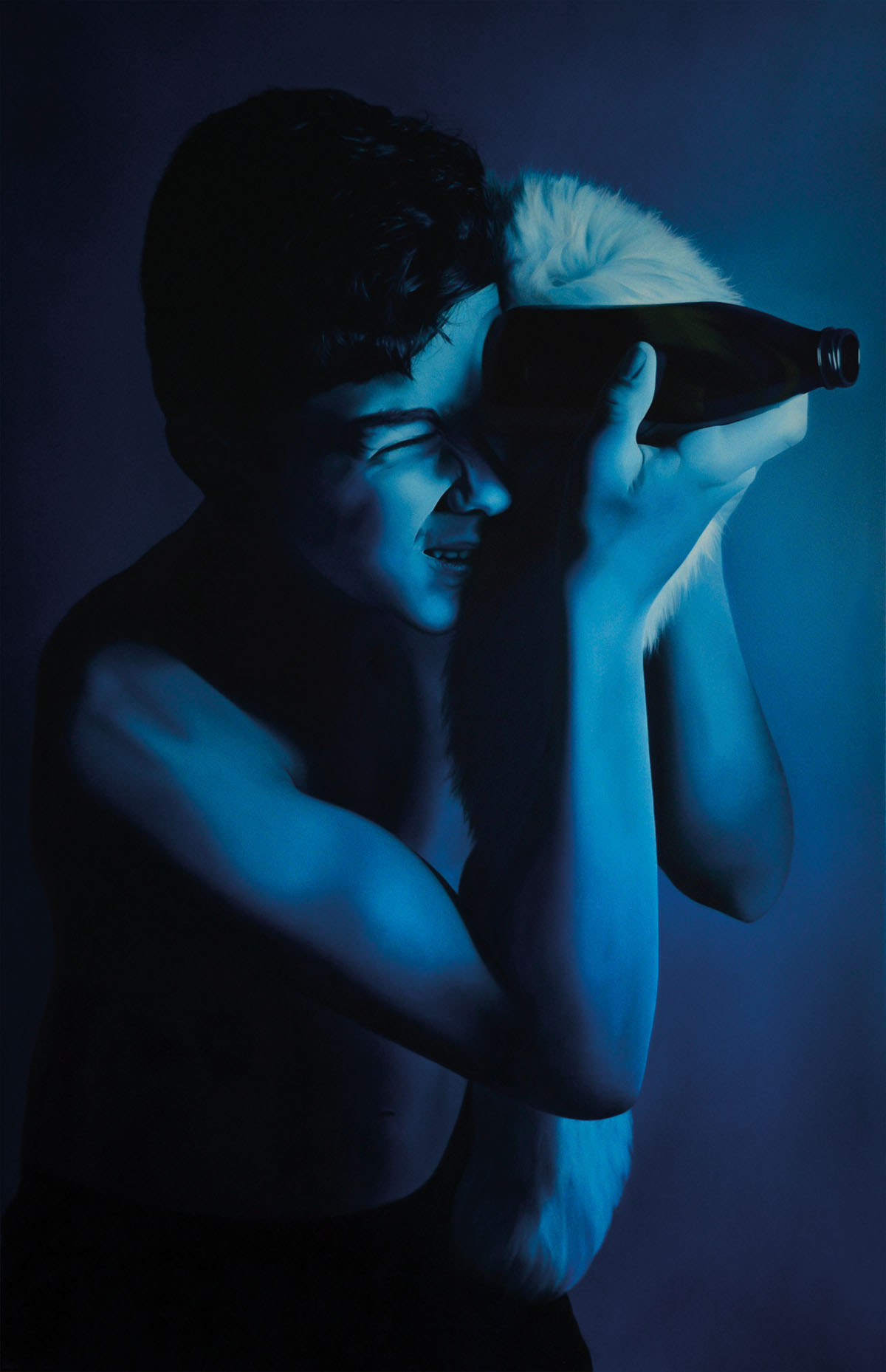

I work with different techniques for each project because my ideas guide the choice of medium and technique. When it comes to painting, as seen in Blue Painting, I use photorealism because this technique invites viewers to spend more time in front of the work. My goal is to hold their attention, making them wonder who the person in the image is, why I chose them, and what the context behind the painting is.

My work is filled with my memories. I want to disrupt the way we have been represented in Western media. I filmed a lot with my phone during my journey because I thought that if I arrived safely, I would use this footage. But once I arrived and saw how our stories were documented and exploited, I felt conflicted. I didn’t want to replicate the same narratives–I wanted to share real stories from my memories.

I often hid my face because we were filmed and photographed without consent. I worried about my family seeing those images, especially since I had no way to contact them at the time. I also questioned whether the people in those images wanted to be shown again, particularly by someone who was there with them. With Eyewitness, I wanted to create a space beyond sectarian narratives and racialised images of masculinity, focusing on the adolescent body born into war and instability. The portrait negotiates personal and political trauma while challenging dominant representations shaped by militarization and occupation. It’s a deeply intimate work—an act of resistance and counter-memory.

When working intensively on a project, how often are you in the studio? Can you describe the process behind one of your paintings?

When I’m fully in a painting, I can work for six to ten hours a day. My process requires a lot of time and attention to detail.

For instance, while I was working on a painting in 2019, my brother, sister, and friends in Iraq were protesting on the streets. I was here, far away from them, and I felt like I couldn’t continue working on my personal story–I needed to do something. Since I couldn’t be there with them, I had to contribute in another way. So, I bought a large roll of paper and started documenting everything that happened day by day.

The term “postmigration“ frequently comes up in discussions about your work. How would you interpret it? Do you believe in the concept of postmigration?

For me, postmigration refers to the social order that follows the experience of migration–the political, cultural, and social transformations that take place. When it comes to my work, I feel that the borders we crossed have changed because of our passage. The landscapes changed; nature changed. The migration process doesn’t only affect individuals or societies–it alters everything around it.

Exhibition: Kunsthalle Wien Preis 2024: Rawan Almukhtar and Ida Kammerloch

Exhibition duration: 23 January 2025–20 April 2025

Venue: Kunsthalle Wien Karlsplatz

www.kunsthallewien.at

Rawan Almukhtar – www.rawanalmukhtar.com, www.instagram.com/rawan_almukhtar

Rawan Almukhtar (b. 1991, Baghdad) has exhibited works at Kunsthalle Karlsplatz Vienna (2025), fjk3 Raum für zeitgenössische Kunst, Vienna (2023); Künstlerhaus Vienna; mumok – Museum of moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna; WIENWOCHE – festival for art and activism, Vienna, und Kulturhaus, Vienna (all 2022); Raumschiff, Linz; Brunnenpassage, Vienna (both 2020). Almukhtar’s work has been nominated for various awards, including the Belvedere Art Award, Vienna (2024 and 2022); the Exile Visual Arts Award by the Körber-Stiftung, Berlin (2023); and the Ishtar Award for Young Artists from the Iraqi Fine Arts Association, Baghdad (2015).