His work has been exhibited at the Foam Gallery in Amsterdam, the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Institute of Islamic Culture in Paris and in festivals around Europe such as IQMF and the Leeds Queer Film Festival. He has worked with the likes of Vice UK, Vogue US, Vogue Italia, Burberry, Puma, Slate, Gucci, Fendi, Farfetch, King Kong, Marie-Claire and L’Officiel, whereas his personal projects tend to focus on the untold stories of Beirut through several documentaries and photo stories that have been exhibited around the world and published in queer publications from around the globe. Whether in still photography or moving images, Abdouni seamlessly shifts between raw aesthetics and overly romanticised visuals.

How do you develop a project?

Quite organically to be honest. It almost always stems from an encounter with someone new. The work I do is very people-driven, and most of my projects have always started with meeting someone new, hearing a story from them that stops me in my tracks. The rest becomes a personal journey of exploring that story further or getting to know that person more, simply because I find them fascinating, and believe the world should stop and listen to their story.

What is the most important characteristic of a photographer?

Wow, I’m not entirely sure how to answer that question. I personally think being a photographer is very difficult. It’s a very sensitive position to be in, where you always need to remind yourself of your intentions and constantly make sure they’re in the right place. Maybe this applies specifically to documentary photographers, I most certainly don’t feel that amount of responsibility when I’m on a commissioned shoot for a commercial brand, let’s say. So I guess I’d say being genuine and well-intentioned are two of the most important characteristics of a documentary photographer, specifically.

Mohamad Abdouni interview

Mohamad Abdouni interview

Mohamad Abdouni interview

How has the coronavirus lockdown changed your life?

How has it not! Similarly to most, if not all artists out there, the biggest hit is financial. Work has all of a sudden come to a halt, and as someone who comes from a country where governmental financial support is not an option, it becomes quite difficult to hustle and try to survive this period on your own. I have however used this time to try and push forward on the two issues of Cold Cuts magazine that we’ve been working on and that have been taking a backseat for a while due to other projects that were „bringing home the bacon“.

I really like the COLD CUTS Magazine. What is the idea behind it?

Cold Cuts is the photo journal exploring queer culture and the Middle East. It began as a passion project, a visual collaboration between friends and photographers, which then developed into a queer Arab and Middle Eastern publication out of a combination of growth and necessity. Representation of queer Middle Eastern cultures was lacking in accuracy, substance and dignity, so Cold Cuts became an organically home-grown platform for queer histories and narratives. The first edition of Cold Cuts was released in 2017 to wide acclaim from the press, featuring the work of over thirty creatives, photographers and performers over 172 pages. It now sits in the library collections of many of the world’s top universities. Following on from its inaugural first issue, Cold Cuts released the award winning documentary Anya Kneez: A Queen in Beirut. The short form documentary offers a glimpse into the life of the boy who revived the Drag scene in the clubs of Beirut, and toured international film festivals around the globe. Then in 2019, our (now sold out!) special edition ‚Doris & Andrea‘ was released to coincide with the exhibition of the same name at the Institute of Islamic Culture in Paris. The issue chronicles the lives of Doris and her genderqueer son Andrea. Together they challenge the social norms of a patriarchal society and the so-called family values of a Middle Eastern family. In the past two years we have developed the content for two whole new editions, comprised of extraordinary photography from across the region, dozens of in depth interviews and profiles, and histories that have taken us way beyond anything we could have ever imagined! The result will be divided in these two upcoming publications.

Representation of queer Middle Eastern cultures was lacking in accuracy, substance and dignity, so Cold Cuts became an organically home-grown platform for queer histories and narratives.

What is the best area to stay in Beirut?

My home, haha! I don’t know it’s very hard to choose, even though I’ve recently made the decision to relocate to Istanbul because of the current political and economic collapse of the country, the relationship I have with Beirut is quite unhealthy, it’s an abusive relationship that I can’t seem to get away from, it’s home, and I love it for all of its downfalls. I guess I would choose the area I grew up in, Tariq Al Jdideh, simply for its sentimental value. It’s a place that has kept its authenticity throughout the years, hasn’t been gentrified and will always smell of my childhood.

What project are you working on now?

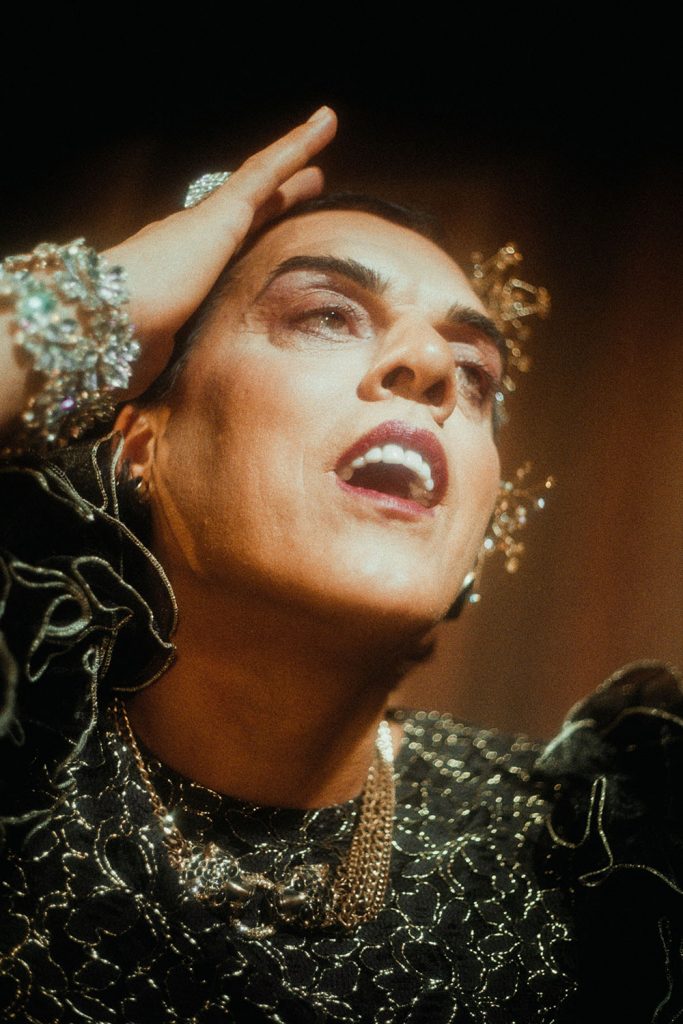

I’m currently working on several projects, but the one I’m mostly excited about is the special edition issue of Cold Cuts Treat Me Like Your Mother: Trans* Histories from Beirut’s Forgotten Past. It compiles studio shoots, interviews and archival imagery to record the untold stories of eleven trans* women living in Beirut, and re-writes the queer history of a war-torn and complexly layered city. The women are aged between their late thirties and late fifties, drawing visibility to an extraordinary community that has long been pushed to the shadows. Each of the ladies sat for portraits, shared their photo archives, and told us their life stories. The women tell the story of a city that is now lost, of war, survival, love, balls, parties, families, beaches, abuse, and jail. The book shows an unprecedented history of queer communities in Beirut. This project is about affording our elders basic human dignity, visibility, love and kindness. This special edition will be published in the Spring of 2021, and was created with support from LGBTQI+ NGO Helem, the Arab Image Foundation, and culture space Station.

Mohamad Abdouni – www.mohamadabdouni.com