Ottavia Lunari: Why did you first approach metal and particularly steel? What were the inherent qualities of this medium that engaged you?

Elli Antoniou: I’ve always liked metal as an aesthetic but because I also worked digitally, the metal was an element rather than the key component but as a material I felt it could be the only that could make sense with the digital realm and sci-fi. For my solo exhibition at Saigon space (Athens, Greece), I created a series of aluminium digital prints, which functioned both sculpturally and in 2D form. Then I further investigated how to create something that looked similar with the prints but using a manual process, and this is how I started using mild steel and make these works that I’m about to show you. I was already familiar with working with chemicals. These mild steel plates required a three step process that includes a controlled corrosion, it is a highly industrial technique called blueing or blackening, performed to prevent rusting of the material but I tried to be more playful experimenting with different concentrations of chemicals or stretching the exposure time. It was a very experimental period but it was covid I guess it made sense. I was trying to draw in a way, without going into figuration/the figurative, I wanted to understand more deeply my material and acknowledge the fact that it is far from being a paintbrush. It is a machine/motor with a round disc that has its own velocity, direction but it does not draw a line, it makes volumes, like a 3D model. So my background in 3D modeling led to this creating of forms in the floating space.

⅙ plates for the installation Ring[TheMemoriesStayWitUs], 2021. Mild steel square tubes, mild steel sheets, motion sensored lights, magnets, 250x140x240 cm.

OL: Tracing back to your comments on time, I deduced an interest in almost performing velocity and acceleration in work. How does temporality posit itself in your practice? How are the notion of presence and present time embraced? I sense that the ephemerality of reflection via which your work is visualised scarcely permits one definite present time to exist. Time is fragmented, repurported and evanescing, late or ahead of the grasps of cognition.

EA: It is exactly that. I’m making work that although located in the present, it is never static, always metamorphosing, event though things appear still, they are constantly becoming something else. I guess this is tied to the techniques that I perform. Back to when I used the chemicals, I felt at some point they were overpowering myself and the work. That sentiment coincided with the beginning of my fascination for stainless steel and also with my residency at Palazzo Monti [Brescia, Italy]. I clearly couldn’t bring all the material with me, so I dedicated all my practice to stainless steel. I soon realised that was it. It is extremely shiny, I can work much better with it and the drawings are more subtle, whereas working on mild steel gets more painterly, I acknowledged that back at that time I was in a way falling into replicating painting, which I wasn’t necessarily interested in. Now I feel stainless steel is just trying to look like itself.

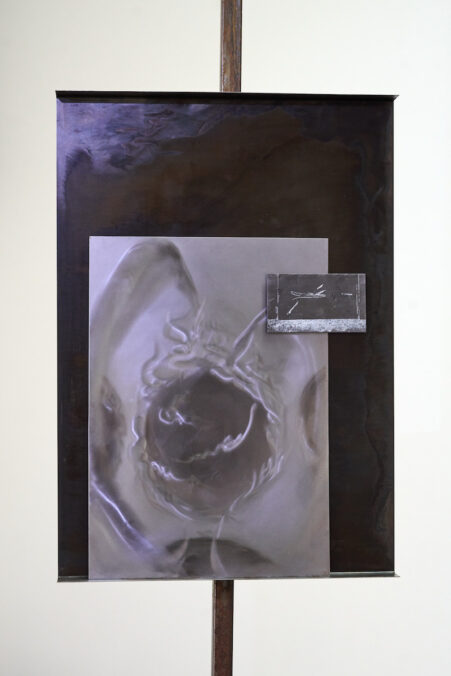

Studio View

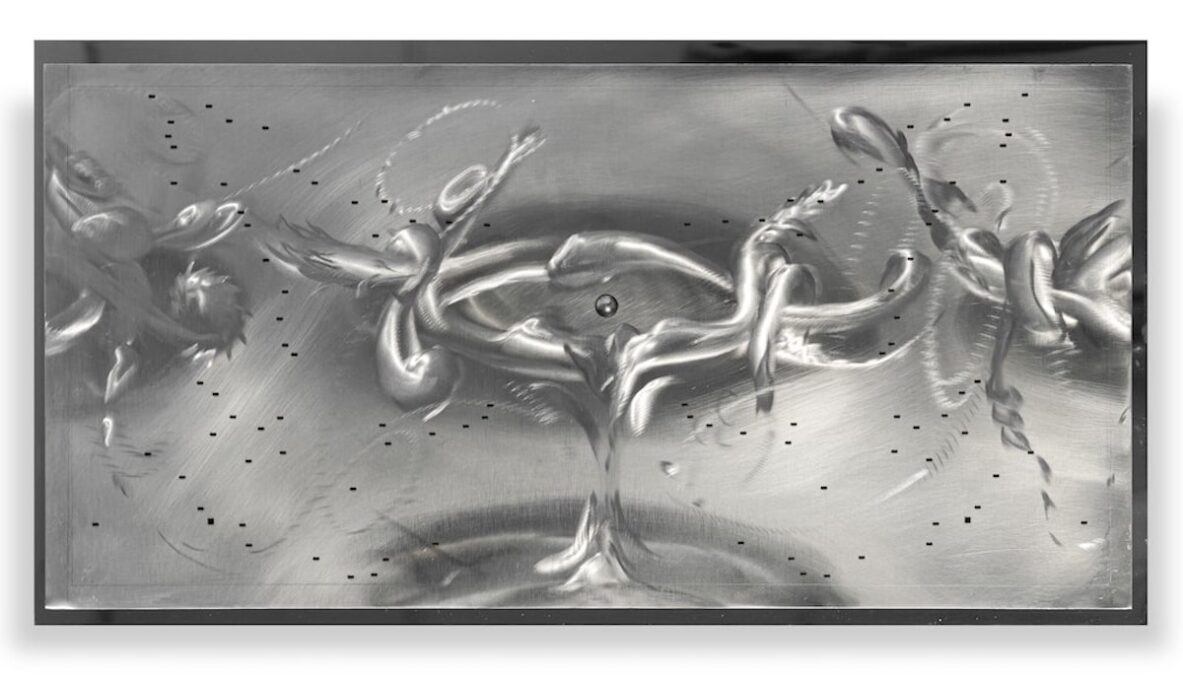

Metaschematism, 2023, Stainless steel sheet, aluminium square tubes, stainless steel sphere, mirror polish stainless steel sheet, 670 x 350 x 20 mm. Photography credits Sal Redpath

OL: You are detaching the work from a pictorial quality. I guess that emulating the painterly gesture could trap you into leaning towards figuration at some point, which is not something I guess you truly want to resort to.

EA: Exaclty. When I understood my material, I finally felt being in the moment, it was en emergence. The metal, the grinder and myself all participate in realising the work. Similarly, when you look at the work, it is not just a piece of metal, it’s the light, and the observing position.

So I decided not to add paint, but to uncover as many colours as the material can bring. That’s really crucial to my practice. You could manipulate the material so much, however it can still remain a piece of metal.

Interview. Elli Antoniou

Interview. Elli Antoniou

OL: It indeed fascinated me from the very beginning how the works while being static compositions are able to border the moving image. A choreography is performed in accordance to the tangentiality of light and spatial placement. It is a glamour, an illusion cast onto someone, a sensory deception.

EA: Yes, it is never simply the plate of metal, but how the surroundings and the viewer allow it to acquire form. Presence and the present time also played a significant role in my digital work. It was a response to how we have always lived with screens. I feel that’s clearly what detaches from your own present. Also, whenever you watch something on a screen, it always belong to the past as it is pre-recorded. Even a videocall is built on delays.

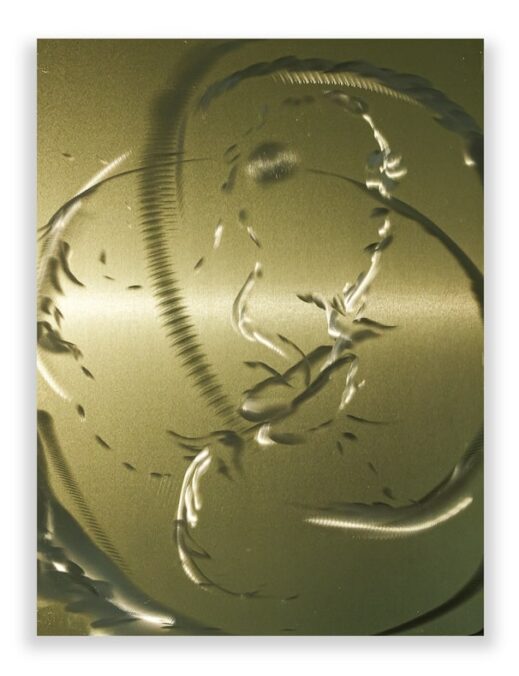

Bending Movements, 2023, Brass sheet, 297 x 400 x 1.2mm, Photography credits Sal Redpath

OL: When I first encountered your work on stainless steel I felt a resemblance to a portal onto an abyss, or a celestial kingdom at times, ceaselessly mutating. The alchemic quest of navigating the fathomless crevices of the inner realm, a bit Yourcenar-esque, maybe? But the works also operated as a mirror reflecting my appearance. Maybe I was in turn projecting something personal? So I started pondering on subjecthood, specifically, how the plasticity allowed by contemporary subjecthood maneuvers reality and drives us relentlessly apart, towards scattered truths that are decreasingly unified, en route to dissociative coddling. Simply put, what is real and what is appearance?

EA: It revolves around that, sure. They have the aesthetic of and function as portals, or screening surfaces, in the way that they enable fictional worlds. My literary references all revolve around this discourse. I realised from the magnetic field theory, star formation, the Sailor Moon transformation, the Baroque, it is always about the moment of becoming, transforming, dissociating, I am so drawn to that. These are the moments that excite me, the in between moments, because they point at metamorphosis which is everywhere although we are not always able to see it. So the idea of the portal is crucial, it promises something else, similarly to a screen. It allows transcendence. Lately I have been into portable altars, the idea that you can close them and take one with you and open it…

OL: And then you immerse yourself and transcend! I believe the notion of the altar is extremely fascinating, as it visualises the moment of transformation. It is a common practice to focus merely on the before and after rather than the processual moments that allow the very shift.

Studio View

EA: Exactly! I feel like I want to make more diptych or triptych now. But the portal definitely has a place in my work, either if you take it with you or in terms of dissociation as we were saying. You don’t have to go somewhere else. Just with these reflections you see a bit of yourself, a bit of your environment, and something else on top, so you become a bit dreamy. There’s always an underlying narrative, however it is not a figurative one, it’s always a metamorphosis. I’m just narrating without a subject, or better, it is about forces, matter and materiality. The brass ones, the smallest ones, I fantasise them as if going under an electron microscope, zooming in you become able to detect moments of energy transformation. Here is when I got inspired by Sailor Moon.

Studio view, 2023

OL: You mentioned you were performing an operation of world-making. I guess fictionality has always animated the bellies of narrators and audiences alike, however, ante post-everything, it retained a sense of political hope. As per the exquisitely contemporary practice of world-making, I imagine it suggests a frantic need for escapism: would you say such elusiveness annihilates an investment in the political discourse arena or rather, given its speculative power, acquires the agency to reconcile us with the recondite of life?

EA: I think there is a bit of both. The work is very existential but at the same time it is a clear response to our contemporary life, technology, the overload of images. I was reading Bifo Berardi’s ‘And: Phenomenology of the end’, Semiotext(e), 2015, where he discussed about the Baroque, of how it was a time of semiotic inflation promised by the expansive attitude of colonisation, a further world was proposed to the West along with a rapid increase of information. Similarly, I think we live in a time of semiotic inflation. Excess of any sources. My response is trying not to be loud, but subtle, in my confronting with technology and the intensity of contemporaneity. And I confront it with a piece of metal, which is never-ending, the ways you look at it are never-ending, but in the end it is the simplest of things, it’s just light. I aim to reduce but now I cannot take anything else from it.

OL: With regards to the duo exhibition you are opening today with Beatrice Vorster at Generation & Display (London). I was wondering if you could expand a bit on the conversation that started it as well as on the title Pinch to zoom. That is for sure a quotidian and likely compulsive gesture, a flaw detector. Sometimes I feel that in a way we rely on that pinch to pave us the way to some moral royalty.

EA: So this space, my studio, used to be shared with artist Beatrice Vorster, with whom I have been friends since my first year in London, 2013. We spent two years together here so our practices were surely linked. Even if she works with sound and I work with metal, at one point we were both doing video, so we shared this element and we frequently discussed screen based work. So pinch to zoom refers to our common ground.

The show is really much about this infinite conversation between individuals that have shared so much of their lives and practices. I used to make work in the day, but she couldn’t because of the air compressor so I started coming here at night. We felt the presence of each other once gone, we left messages… so the show is about this mark-making of the space that we both inhabited, by time we influenced each other.

Left SenseOfRelief [NeutralAngels], 2023, digital print, pasted, Elli Antoniou. Courtesy of Joanna Wierzbicka|Right mixtape4, 2023, digital print, pasted, Beatrice Vorster. Courtesy of Joanna Wierzbicka

There’s a big sculptural structure which we have collaborated together on, and prints, which I had never ventured myself in. We experimented a lot with mediums that did not necessarily belong to us in the past while keeping our own essence. I worked digitally on prints created from photographs from my metal drawings and manipulated them to resemble a low-relief. I learned that technique from gaming. You can get this low-relief effect from images when creating textures for virtual world. When the metal drawing becomes a digital image you lose trace of what you are looking at. Any elements you put into this work, as the final effect is homogenous, it absorbs everything. There are notes in that even, but they look like engravings.

OL: When you were saying that you left traces of yourself, I thought you both were living out of the traces of your ghosts, in a way. The presence was still there but it was there for the other person to catch it. When one person would step in, they could catch the vibe, the scent of the other…I don’t know, I keeping thinking about this being the ghost of each other, to the point of being the same person. You continue each other’s gestures.

Exhibition view, pinch to zoom, 2023, Generation & Display. Courtesy of Joanna Wierzbicka

OL: And what about Metaschematism: a film study on metaperfomativism which features your steel works. How do those pieces dwell in the context of the moving image? Do they become ornamental, do they lean towards decoration? I’m aware this question is rhetorical to a certain extent.

EA: If they become an object, I guess. I proposed to Yasmin [Vardi, filmmaker] to do this film together for multiple reasons. I’m used to buying all the metals and leaving them there and after some time at the studio, I feel like I know what each piece should host or embody, I have to sit with the metal sheets for some time. They gradually become like characters, each feels very specific and individual, they are different characters of something that connected them, so I tried to include elements of one inside the other plate of metal. So a plot started to emerge. Trying to photograph this collection of work I made during the Roman Road program, I realised there’s not a single true picture of the work, there’s a multitude because of light affecting it. So film just made sense. The works exist together. I found this car mechanic who allowed us to shoot. It was fun because Yasmin and I had to improvise a lot, we choreographed a lot. So it is not truly decorative, but mostly a way to capture the work for its true essence.

*pinch to zoom will run until October 1st at Generation & Display, London – www.generationanddisplay.com. Open by appointment. Works by Elli Antoniou and Beatrice Vorster. Curated by Amélie McKee.

Elli Antoniou (b.1995, U.K.) grew up in Athens, Greece. She currently lives and works in London, U.K. Antoniou holds an MA Degree in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art (2018-2020), with a scholarship from NEON Organisation for Culture and Development and a BA in Fine Art & History of Art from Goldsmiths University of London (2014- 2017). She was commissioned to create new work for the group exhibition Doomed companions, unsubstantial shades, Hellenic Residence, London (2022) an exhibition, supported by NEON. Her first solo show Overlapping moments of a slightly present (2021) was hosted by Saigon, Athens, Greece. She has previously shown work at FRAC Champagne-Ardenne, France (2020) and Mécènes du Sud, Montpellier, France (2019). Antoniou has been awarded the ARTWORKS 2022-23 Fellowship by Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Greece. She has participated at the Palazzo Monti residency programme (2023), Brescia, Italy and at the Roman Road studios programme, London, U.K. (2023) – https://elliantoniou.com/

Ottavia Lunari is a writer based in Milan – www.instagram.com/empty_oyster/