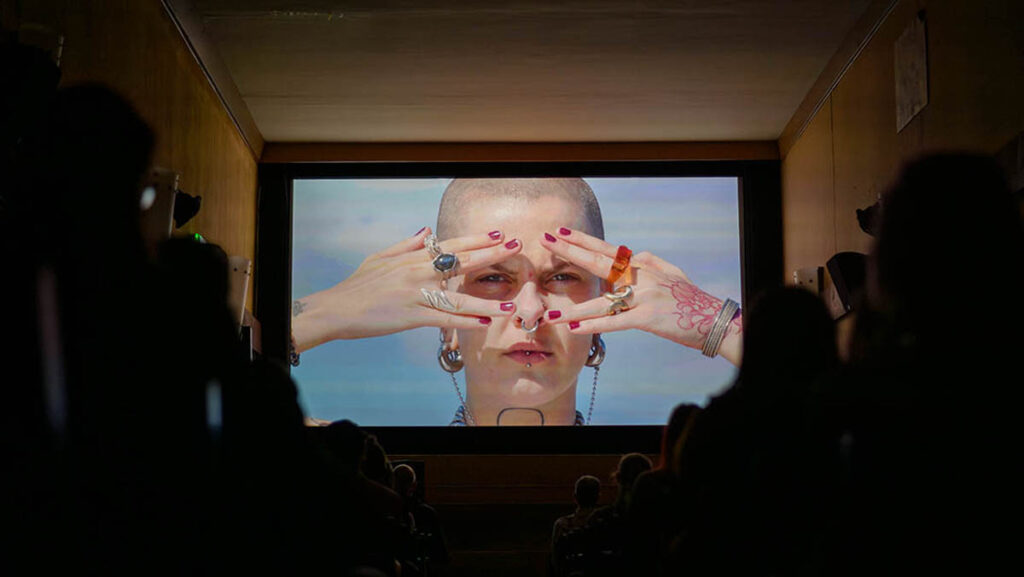

I would like to start with the question of spectatorship in the context of your works‘ placement in the gallery, right at the entrance. What impact do you think the installation could have on people in terms of movement in the gallery space?

I love the idea that people could interact with the work. For the opening especially, it is pretty busy here, and yes, there is a chance that people will touch it, move it, shake it, and go inside it. Because it takes up a lot of room, you almost cannot pass it; you are also forced to physically relate to it and move through it. People are welcome to search for the edges of it, check its flexibility, and find the space that feels comfortable to them. Another thing I enjoy about the setup is the contrast between the installation hanging from the ceiling and the small works on the walls; the works on the walls are fragile and made of ceramic.

How did you work on the installation? It came in fragments, and you assembled it right here on-site?

I have exhibited this work in other spaces before, but before I sent it to the gezwanzig gallery, I established parts. To all the rubber stripes, I attached the metal closing systems so the assembly together would be as flexible and modular as possible. When I arrived in Vienna at the gallery and started working on the installation, I just laid the parts on the floor and started lifting them and connecting them. It was an action to set it up; the process played a big role in this work and the final position in the space. I had it planned, but I also let it play out during the process. The material is not something that could break, and this is why there is this advanced power to move the installation from place to place and be easily transported and show the same idea in different places and contexts. It almost always has this side-specific element to it, and this is what I find very important.

Interestingly, you mention this practical aspect of the whole installation, its ability to be easily packed and transported. This is very interesting because, in general, your work refers to the systems of society and their functionality and standardizations in European and Western countries.

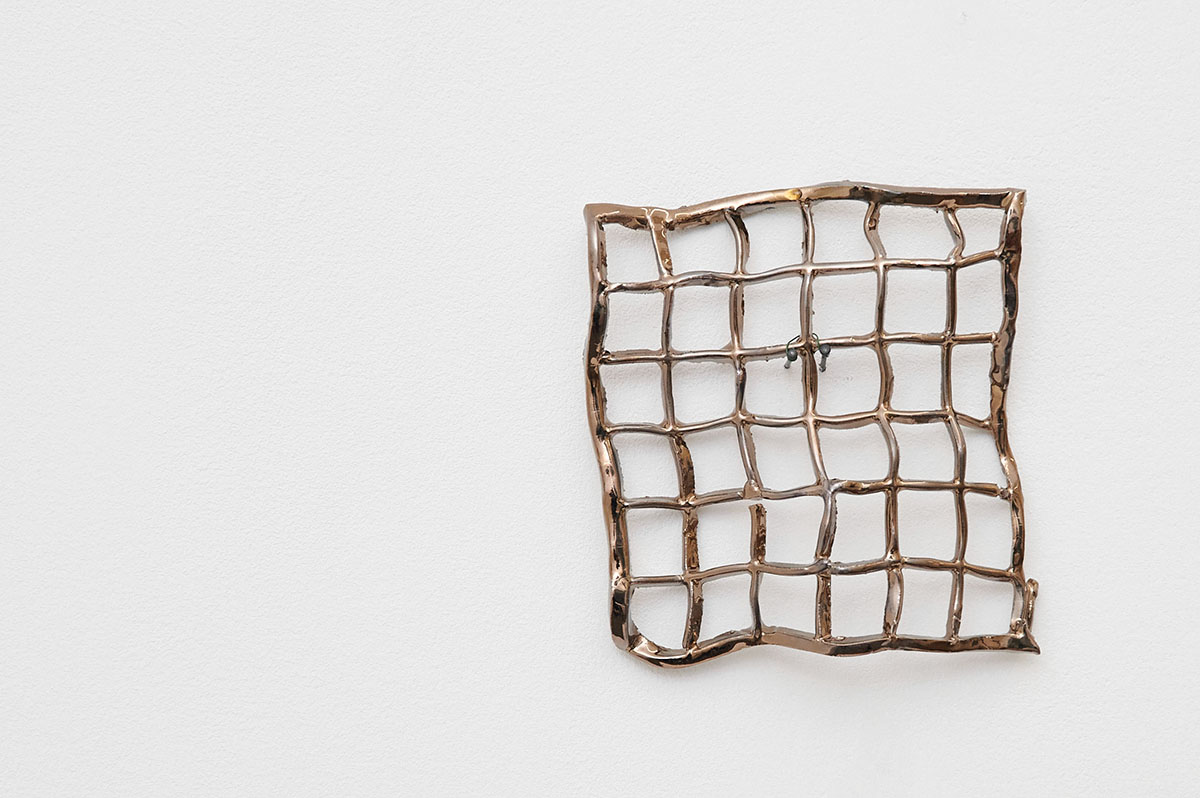

My work on that system, and I like to believe romantically, sometimes breaks that system. But I am very, very aware that I need those same systems; I also need my inner systems. I need to feel this control over stuff, and I need a sort of oversight of what I’m doing. I have some kind of love-hate relationship with systems, I guess, so by making these works, I also learn a lot about myself and how I think and how I relate to myself and my surroundings and why I do that and where this behavior or thinking comes from. In general, my work is philosophy, but then in a physical way. I am sometimes giving answers with my works but also proposing questions by using different materials; steel bends, wood breaks, and ceramics are really organic and flexible, but then after you have baked it, it’s really breakable and so on. The key to my work lies in how I transfer philosophies into materials with different qualities.

How intuitive is your process of working, and how much of it are you planning and calculating? What I was also thinking when I entered the room was how you played with the floor plan from the bird’s perspective. I am doing this often; it can become a drawing, so the work on itself?

I am making choices not only in my work but also in my private life. So I call them design choices. So if I, for example, buy these shoes, I buy not only the material they are made of but also all the choices the designer made to make the shoes. I buy a rubber, I buy a logo and thread that connects it in shape, and then all these choices have consequences. This rubber comes from a tree, and the leather comes from an animal, and so there are consequences to the choices we make when we humans design our systems. And I think our systems are too focused on control. We try to control our surroundings, and then we make this grid where we try to fit ourselves in, both in an abstract and physical way.

For example, when you are landing an airplane in the Netherlands, when you look down, the only thing you see is a great grid in the whole country that is flat, and the nature is manipulated in the grid; this is how the infrastructure is also planned.

I think the way we relate to our surroundings, and especially to nature, is from a pespective of control. But the thing is, with the urgent problems we have in our relationship with nature, we never think of the fact that nature has so many possibilities; nature can be self-healing, but if you control it, a lot of these possibilities go away. If we could let it go a bit, we could be surprised by how nature alone can solve the problems.

In the last four to five years, I focused on the grid as a notion that it is in all my works. I published my first monograph, called GRID, in 2023; it is a publication that shows my ongoing visual research project. Grid—A Visual Research Project provides insight into my long-term visual research, in which I both literally and figuratively subject grids to the unpredictability of external forces and influences that distort and transform them. The book documents my work across various media, featuring images from exhibitions as well as glimpses into my creative process in the studio. Beyond my own visual exploration, I invited individuals from diverse fields outside the arts—including a psychologist, philosopher, microbiologist, and urban planner—to reflect on my work. I asked them whether they encounter grids within their own disciplines or daily lives, how they relate to them, and what impact these structures have on their thinking and practice.

How do you use control over your work in the process? You mention that if there is too much pressure on something in the case of work material, it could lose the ability to perform.

Well, that’s a bit of a struggle. I try to create a situation in my working space that I can lose control of. But this situation is pretty controlled; otherwise, it will not function. I am using weight and pressure to manipulate materials, for example, metal, and I am losing control over the final look of the work because I don’t have the ability to control it. I am just triggering the situation where an unexpected situation could happen. But then I will make a final decision when the work is finished.

What I learned early in my process is that the things that I lose control of and that become uncontrollable in a way become something that’s usually way better than the things I think of. So, um, I kind of accepted that and tried to work with it, and so it’s always about losing control, but preferably in as controlled a possible situation; it is also the way I was culturally taught.

What are you reading and watching in your free time, and does this also in some way influence your work?

I love to read fiction, but I also read nonfiction and a lot of philosophical texts, any kind of ideas that inspire me to think of stuff in new and other ways. I am a fan of zombie apocalypse stories, for example, „The Last of Us,“ the series I enjoy at the moment. I love that stuff because it shows us the situation when everything is broken down, how something new grows, and how new opportunities are opening; it is about surviving and how it is to be a human. It also makes me often remember how it is a privilege to work in art and have the capacity to ask those questions.

Solo exhibition: Art van Triest – Linear Nonlinear

Exhibition duration: 20.03-16.05.2025

Opening times: Wednesday till Friday: 11 AM-6 PM | Saturday: 11 AM-3 PM

Address and contact:

gezwanzig gallery

Gumpendorfer Straße 20, 1060 Vienna, Austria

www.gezwanzig.com

www.instagram.com/gezwanzig/

Art van Triest – www.artvantriest.nl, www.instagram.com/artvantriest/

Control is the main theme in the work of Art van Triest (1983, NL). The human tendency to exorcise his fundamental fear and uncertainty manifests itself in various forms of order, a system that satisfies our need for control. For van Triest, the contrast between built or generated forms with a geometric character and whimsical organic forms created by natural processes is a visual metaphor for how reality escapes the system in which we try to contain it.

»The Linearity of Feasibility«—Van Triest’s critical view of order and categorization. Art van Triest is a Dutch artist who specializes in installations, sculptures, and visual art. In his works, he addresses the human tendency to control the world through systems and orders in order to cope with fears and insecurities. This “order” is reflected in recurring motifs such as grids, structures, and grid lines, which for him symbolize Western rational thinking. In his works, Van Triest questions the linearity of our ideal of feasibility and the tendency to categorize everything. He sees the grid as too direct a method of dealing with reality, and his works offer a visual antithesis to the simplification and standardization of our environment and way of thinking.