Erka Shalari: I would like to start our conversation with your video work, Seabird. I find the moment where it appears as though you are swallowing the containers particularly intriguing, I also like how large your hands look. How did you start to work with video art, and if you could talk a bit about the aesthetics of this video, like how you use colour, sound, and movement?

Sena Başöz: Seabird is a work of mine that has a special place in my heart. I like that we are starting from there. When I am working with video, the crucial thing for me is to create the right atmosphere to make a miracle-like moment within the mundane work. I use fiction quite often in my work. I believe to react to the truth, we need fiction. Otherwise, the world is too complex. I studied economics before art, and I learned about fiction there. All economics articles begin with fiction. They are after the truth about, let’s say, something like the relationship between inflation and the unemployment rate, and the first thing to do is to create a fictive world. The assumptions at the beginning of an article are wild like there are only two goods in the whole universe: guns and apples. The aim is to simplify the universe so that we can initiate calculations. We can put everything into equations. I liken using fictive scenarios in my artwork to that. After I studied economics, I worked in finance for 3,5 years. I was working at Reuters for the financial data screens. First, I didn’t dare to study art, and then when I found the courage to pursue art as a career, I didn’t know how to turn my life around. I was miserable. I started making videos in the office space to document my life there. Working with video came as a natural need for me to survive working 9 to 6 in a business plaza in front of a computer looking at numbers and codes all day.

I went and bought a handy cam just for this purpose. The video works Nobody is Indispensable and Swimming Across, for example, were shot on my office days. They were like a visual diary. But these videos, later on, constituted my application portfolio to Bard College MFA.

Seabird is about imagining being part of something that I am not part of. I am not part of the maritime industry. But there I am eating the containers while on the ferry. Everything starts with imagination. To obtain power one must imagine it first.

I imagine I have control over this system. I wanted the video to be captivating and reflect the beautiful colours of the Bosphorus. The Bosphorus always triggers the imagination. I wanted the sound to help focus on what is happening. Just the sea, the engine, the seagulls. Surely the crunch sounds when I bite are exaggerated and loud, and I wanted the video to have a carefree, easy, warm vibe. As if to say, “I can be this powerful very easily without any sweat”. I wanted it to be two channels to underline the miracle I am imagining by showing the scale. In the other video shot in the port, I am so small compared to the containers and we used aerial shots to show me getting lost between them like an ant. Everything is bigger than me: the vehicles, the operation, the system. Over 90 % of world trade is done through Maritime Transport. In the first video, as you say, I am the giant. I have the giant hands and the giant mouth that swallows the containers. In reality, I am only a consumer of the goods within the containers. But maybe that too has a power.

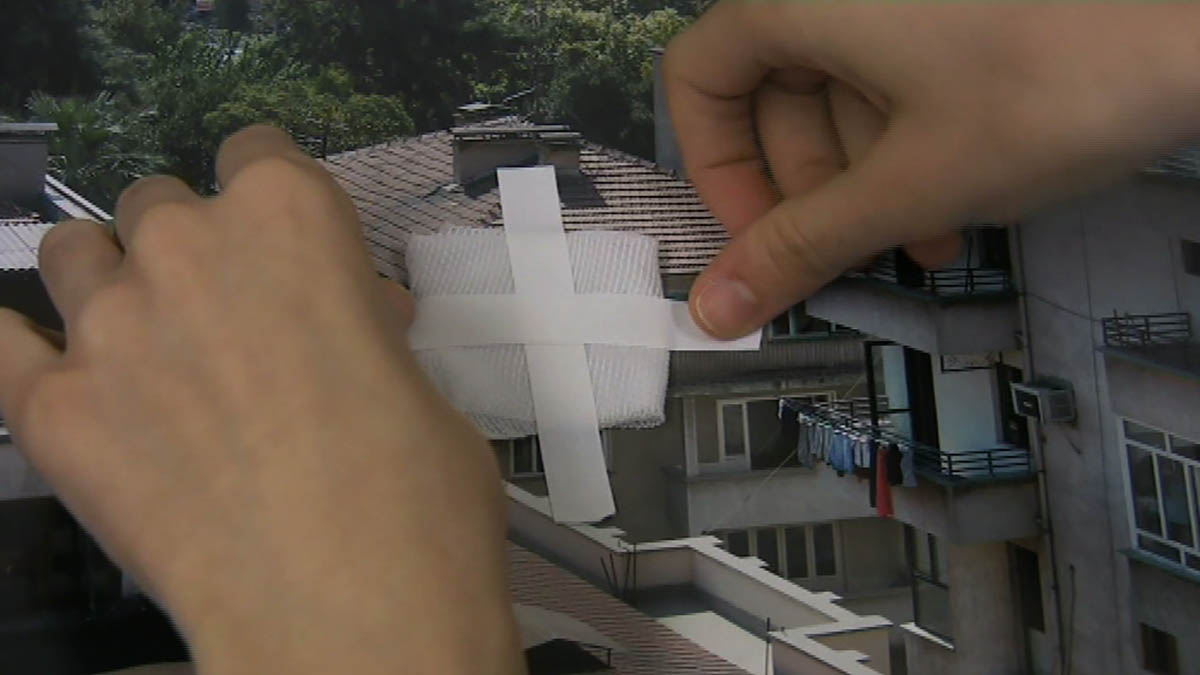

ESH: I like the repeating element that you are the giant. Also, in the video Doctoring, you always have huge hands when you clean or heal. Do you want to tell something more about this work and the elements behind it?

SB: When I made this work, I was in my nurse persona. I was a wounded nurse, who was supposed to heal others while she was herself sick. In that period, I realized I could manipulate reality through fiction, through imagination and artistic creativity. What has already happened cannot be reversed or fixed, but in Doctoring I play with that idea. Because only art can create such a window. Still images allow manipulation. Once you photograph things, you can stop and think about them.

This performative video is composed of actions of a nurse looking for ways to heal herself through creative imagination. She is looking down on photos from her surroundings. For example, one house I bandaged is my grandfather’s house. My hands make it happen. All is possible then. Art makes it possible.

ESH: Besides the office in Reuters, what do you think brought you to arts?

SB: I always wanted to be an artist as far as I can remember. The creative act is an act of freeing, freeing the accumulated inside us. I think that is what attracted me to the arts. My art generally stems from where I get stuck. I was feeling stuck in the office and the office videos happened. I sometimes feel stuck and powerless within the capitalist system and Seabird happened. It is a way to free myself as well.

ESH: I don’t know why, but a show that you had in Basel and all those kinds of flags that surround the bed and that you placed in various places comes into my thoughts. Would you like to elucidate on it?

SB: The inspiration for that project in Basel came while I was in Basel researching institutional archives. My first impulse was to create a work on institutional archives there, but once I got there, I realized what they keep about white Swiss people versus the immigrants is very different in their institutional archives. In Stadt Archive Basel, they keep ethnographic info about the locals, but about immigrants they only keep folders of how they breach the immigration law.

The shelf of these folders reaches 1km, the longest of its kind in Switzerland. Therefore, I started having these dialogues about what people would like to keep. I talked to archivists and immigrants. I asked them the same questions. I used the help of fiction once again. And imagined a time when the river Rhine dries up. I am always thinking about the end and death but not as a depressing thing. The acknowledgment of the end intensifies my questions, the urgency helps me look right in the face of issues. It helps us talk about the essence more directly rather than walk around things.

ESH: Where does your work begin? How is your relationship with the studio?

SB: How do I start? I don’t envision the work in my studio. The studio work comes last when I am in the production phase. My work starts when I am moving around. I am inspired by what’s going on around me. When I was in the office my inspiration was the office, when I am on the ferry it’s the port. The initial concept is formed like that. Then, I have a studio phase to realize the work. I like working in my studio, but I don’t have a routine. It gets intense before exhibitions. Then I don’t go to the studio at all for a while.

ESH: I like it when artists take breaks from the studio for a while. It is important to not be in all-time in production modus.

SB: I agree about breaks. Doing nothing is so important. My education is that one always has to be efficient, effective, and productive and I used to judge myself when I took breaks, but now I know very well: Creativity needs breaks, void, nothingness, all possibility lies there.

ESH: What role does Istanbul play in your work?

SB: I believe Istanbul gives every artist living in its inspiration. The inspirational material in Istanbul is endless. There are worlds within worlds. The opportunities to produce work are endless. You can find endless material, good craftsmen, and tradition. Istanbul is also where I see exhibitions and follow my colleague’s works. But Istanbul is also a very exhausting city. Logistically, economically, socially, and politically. Istanbul nourishes me as an artist and it is the ground where my art grows from but I have to be careful not to exhaust myself. One needs to take breaks from Istanbul.

ESH: For what are the artistic residencies the best?

SB: Artistic residencies are best for seeing new art, and new art worlds, experiencing new modes of art production and focusing. Also, to get to know other artists, make friends, and have great dinner parties. Artists are like one big family, I believe. That connection is precious.

ESH: Things that continue repeating in your work?

SB: Things that repeat in my work are:

Miracle, like moments within the mundane created using cheap materials and easy tricks. Those containers are made from communion wafers. I don’t like digital special effects.

Performativity.

Birds, birds appear a lot. There is a scene in my video “Be the Doctor Practice Nursing” where I free birds from a refrigerator freezer. Also in my video “The Box” I free birds from a woman’s hair. And there is Forough, with hundreds of taxidermy bird photos flapping with wind.

Cubes, rectangles. This is a form I come back to again and again. They represent the rational mind, the categories. I try to transform the cube, I create alternative cubes. I realize now that containers are also cubes.

Fragmented things that disperse, like bird feathers, seaweed, human hair, shredded archives, and fragmented sentences. I research the possibility of them coming together.

ESH: You told me that you were working for a solo show. How is it conceived?

SB: My solo show “Inevitable Choreography” opened recently on the 16th of December and is composed of all new productions. The show focuses on cycles and movement of items from my archive which bring into mind the movement of the body around these objects across space and time. It reflects my current interests and current artistic research. The body is transitory and vulnerable while objects, archives, buildings, monuments, and political structures operate on a different time cycle that outlives us. My performance piece, entitled Slalom (2022), investigates how a moving body can activate an institutional archive. Since then, I realized that, in addition to the body, objects also move, and this reciprocal movement could be perceived as a choreography of impermanence.

My works seek ways of interacting with what is considered out of reach and experimentally regenerating what is considered frozen-dead-stale-lost. I often work with archives as the only tangible material between life and death.

My recent work delves into the body as an archive and movement as a tool to regenerate. This is a time that I am aware that the archive is also not still. It moves. Even if it stays where it is, there is decay which is an internal movement. I like thinking about all these. I am interested in archives that are lost.

ESH: It is not so often for me to ask artists who are their supporters, but I would love to ask you something about collecting, places, people, and foundations that have bought your work or supported your production. In the end, we are also workers, and there is an economic background in the art ecosystem. How do you position yourself within these dynamics such as working with a gallery?

SB: I recently started working with a gallery and my solo show Inevitable Choreography opened there at Zilberman Gallery. It is my first show with them. Working with a gallery, I believe will teach me a lot about how the art market functions. I believe in a collectorship that collects to support the artist and their work. However, not all art production depends on the market, and I think this is very valuable to support, especially the production of work that is harder to market, such as performances or videos. Thanks to funding agencies such as SAHA Foundation in Turkey, we can sustain these productions. For example, my recent performance piece, Slalom, was supported by Block Universe Performance Art Festival London, Delfina Foundation, and SAHA Foundation with support from Wellcome Collection, TAVROS and Yapı Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat for different iterations. This work was a crucial step for my artistic research. At the beginning of the year, I had a solo show at Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat and they commissioned five new works. The newly founded alternative art space HARA commissioned two new works. I am so glad these agencies and platforms exist.

Image credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz for Zilberman Gallery

ESH: How is the work with curators? I’m particularly interested when it comes to their role in solo shows, as i think that solo exhibitions involve a greater degree of intimacy and collaborative engagement.

SB: I love working with a good curator. I learn so much from that mutual creative space. A recent very good example was working with Burcu Çimen and Didem Yazıcı as curators for my solo show Possibilities of Healing at Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat. It was the curators‘ vision to put my early videos made in the office at the entrance of the exhibition. This led to the show at Exile curated by Pınar Öğrenci who saw these works in my solo and the show in Exile led to us meeting and to this interview. On my own, I would never have imagined putting these very early works together with my new commissions.

ESH: 6 places in Istanbul that are almost magical to you.

The ferry that goes from Karaköy to Kadıköy or reverse direction like in my video Seabird; Rüstem Paşa Mosque with its beautiful 16th-century ceramic tiles and its courtyard hidden within busy streets; Boğaziçi University South Campus with its stunning view, where I first met Istanbul; Istanbul Archeological Museum; Agios Dimitrios Agiasma in Kuruçeşme, the unexpected cave and the holy water at the end; Finding some historic street corner in Fatih, feels like a time tunnel.

ESH: There is an Instagram post of yours that is very dear to me. We can see you in your childhood apartment, running.

SB: Childhood is where trauma is. One learns to look at it, be with it, and re-visit it years later. My recent work I Told You Everything refers to childhood as an archive and attempts to access it through the body. I love that you picked that image. I feel free in that image, revisiting my childhood home. I am at peace. I am free. This image relates so much to my current solo show. This house is now somebody else’s house, and I revisited it. It’s part of our choreography with that space which once was my whole world.

Notes:

1. I encountered Sena Başöz’s work at the Curated by Festival at the Exile Gallery (A Group Show curated by Pınar Öğrenci)

2. Inevitable Choreography, Sena Başöz’s solo exhibition, can be seen until February 24, 2024, at Zilberman Gallery in Istanbul.

Sena Başöz (1980, Izmir) works and lives in Istanbul. She received her BA in Economics from Boğaziçi University in 2002 and her MFA from Bard College Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts in Film and Video in 2010. Her recent solo exhibitions and performances include „Inevitable Choreography“, Zilberman Gallery, Istanbul (2023); „Possibilities of Healing“, Yapı Kredi Culture Arts and Publishing, Istanbul (2023); “Slalom”, Wellcome Collection, London (2022); “Clam”, Matsutake at Librairie Yvon Lambert, Paris (2021); “Ars Oblivionis”, Lotsremark Projekte, Basel (2020); and “Holdad on Let go”, MO-NO-HA Seongsu, Seoul (2020). She participated in artist residencies at Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris (2017), Atelierhaus Salzamt, Linz (2010) and Delfina Foundation, London (2020-2022). – www.senabasoz.info, www.instagram.com/senabasoz

Erka Shalari is an art writer and editor. Her work is committed to uncovering distinctive artistic positions in contemporary art. The work methodology is strongly influenced by psychology, epistemological works, as well as affects and rituals. The individuals following each interview are intertwined with a file rouge not only with the writer but also with one another, creating so curated series and episodes.