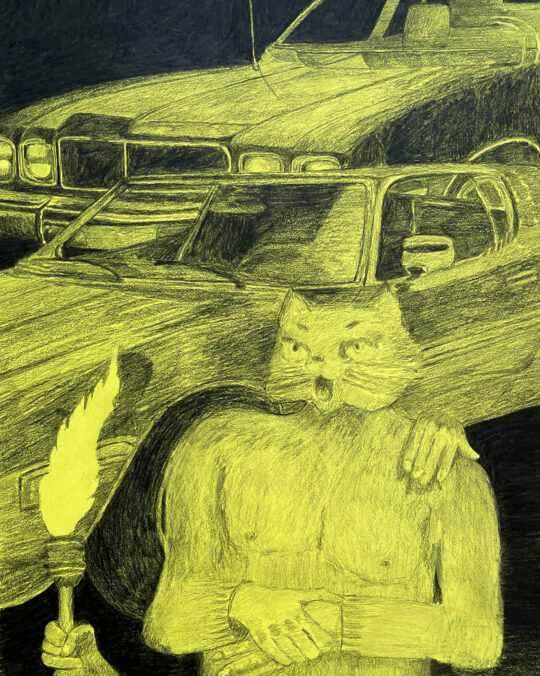

Julia Zastava is a multidisciplinary artist who works across drawing, installation, sound, text, and performance. Her practice explores themes of transition processes, narrative questions, misplaced shadows, and collapsing intentions. By blurring the boundaries between human/non-human, past/future, she opens up space for novelty and surprise, where the ordinary becomes extraordinary.

You emphasize transition and narration. How do these ideas shape your works?

For the last couple of years, I have been exploring the topic of processes of transition and expanded storytelling. Researching themes of fragmented reality and speculative fiction, I have been creating experiences with and alongside the structure of things; investigating how things relate and transform in a cross-disciplinary exploration. I employ speculative fiction not as a genre but as a method to destabilize the present by disrupting logic and materiality. For me, it’s a tool to unsettle the ‘real,’ creating spaces where objects and narratives refuse to cohere and instead hover in perpetual states of potential and becoming. I often start with something familiar and mundane—the everyday things we all know. Then, I try to twist them to subvert the expectations and create a feeling of disorientation. By working within the boundaries of the known, I can create a tension that blurs the line between the familiar and the unknown. Because of this, my approach to storytelling rejects the hierarchy of ‘plot’ in favour of a constellation of unstable elements. Just as my characters defy classification and do not fit into specific roles or identities.

Your work from 2023, “Bad Robot _extra Breath”, was shown at the Belvedere. How does the institutional space influence the way you think about your themes of transformation?

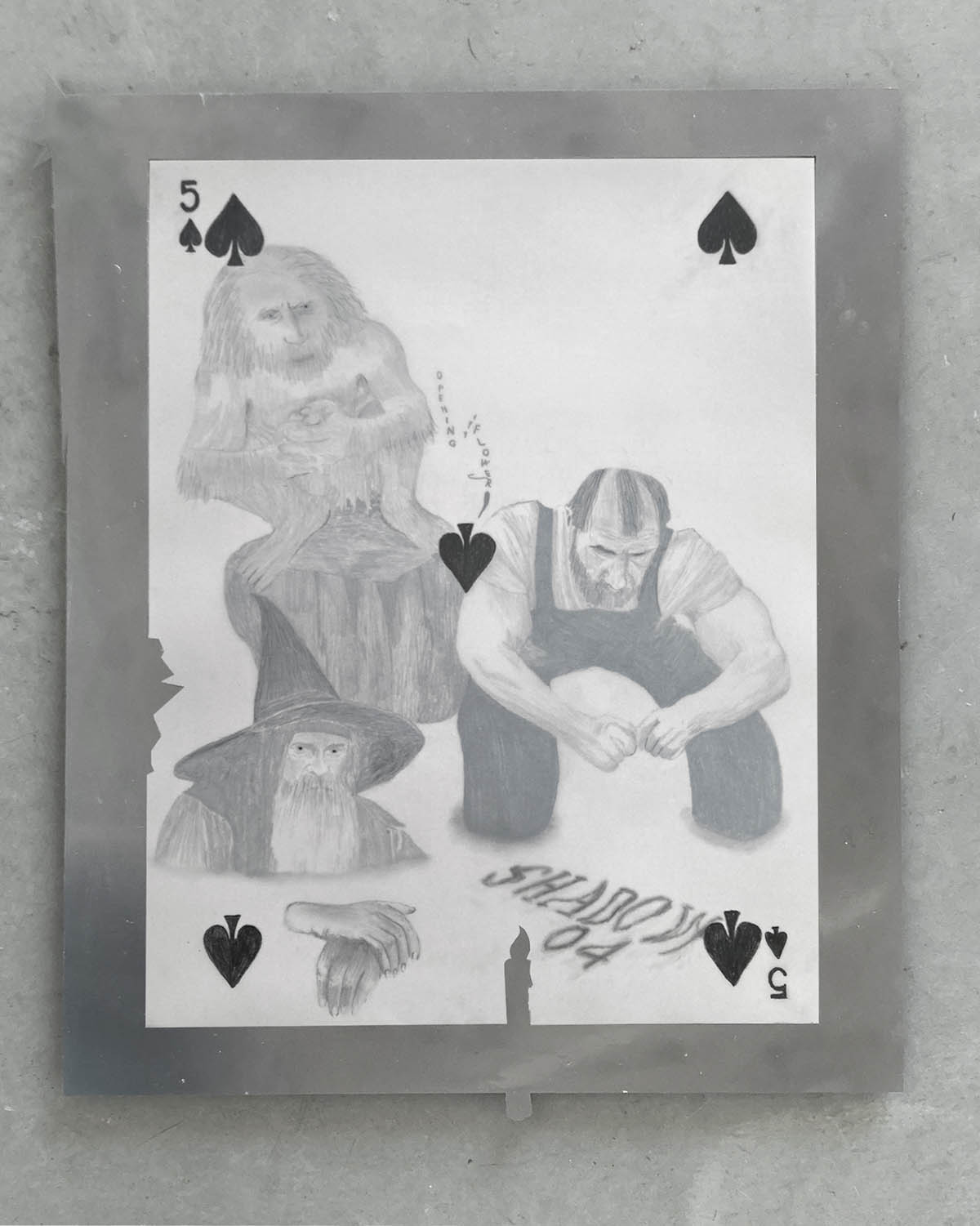

When I work in institutions, I notice I try to show more “finished” works, while in offspaces I would go more for focusing on creating an experience, a situation, building the display around visual illusions and special effects. I think in general my initial education in directing is stronger than my secondary art education: I perceive the exhibition as sort of a stage or even a movie scene, where I am thinking of a particular effect that the spectator should have. So when I work in an institution, I always try to stay more compact in my statement as a visual artist solely. Luckily, by the time I got an invitation from Belvedere, I had just finished a new series of drawings, Bad Robot _extra Breath, and was looking for a place to show them, so it was a perfect match. In this series, I was contemplating the reinvention of meanings and notions in a world where the relations of things that build its reality seem to have been reshaped by a glitch. So I was thinking how I could create a more complex environment and approach the theme of a glitch also in my sculptures. And bingo! I work with biodegradable polyester, and it is usually mistaken for wax. So I decided to equip my objects with wicks, turning them into almost-candles. That’s how objects for incomprehensible actions appeared in my oeuvre. Funny enough, once my non-wax objects were turned into almost-candles, people started asking me more: but that’s not a candle, right? But what is it? So I reached a never-ending transformation, a transformation into the unknown.

Trauma, magic, sexuality, and the uncanny recur in your work — how do you balance these darker themes with a sense of wonder or hope?

Trauma and sexuality are very old themes that I don’t explore anymore. Over the years, they have been replaced in my practice by failure and fetishism. And these two themes, plus the magic and the uncanny, are fascinating tools for me to dissolve the bonds of conventional logic, letting the narratives that emerge hover in an unresolved state of possibility. So I don’t think they are dark, on opposite they are full of vital possibilities of recreation and hacking perception. It’s about that thrilling moment when your brain’s autopilot fails, and you have to re-learn how to see. I am in general interested in mistakes and slips in the system, in misplaced shadows in otherness, and in the invisible things as they are offering to me the marvel, the expansion of meanings and functions, when the known world stutters and reveals a different set of possibilities. It’s all about the pleasure of thinking and reinventing the ways of thinking, not necessarily knowing. Against a world obsessed with resolution, my work embraces the unresolved, where not-knowing becomes a form of resistance. I think I am less interested in answers than in propelling the viewer into a state of active questioning. Rather, I am asking: Can we train to sit with the unresolved, to perceive agency in the marginal and find kinship in reimagining coexistence?

How do personal memories and collective histories intertwine in your work?

I draw inspiration from everyday events and distorted memories. But instead of illustrating them, I try to experiment with the possible translation of these specific phenomena/occurrences into a work of art. I always start projects with the title and concentrate on collecting adjectives, associations, fragments, scenes, everything that creates a poetic scape. I repeatedly return to changing motifs that question language and meaning. Investigating the pleasure of the possibility of the impossible, through repetition and variation, I create a shifting narrative space. I try to dissolve the rigid connections between word and image by allowing for ambiguity and transformation, to create a form that I can then fill with other layers of meaning, turning it into a vehicle of the unexpected.

What role do emotionally or spiritually charged motives and materials play in your works?

I am not sure if I use spiritually charged motives or materials, but I am sure I am fully spiritually charged. As for emotions, I think I like to leave the viewer puzzled and smiling. Like when you read a good poem.

Julia Zastava www.instagram.com/juliazastava/ www.juliazastava.com/