Understood as available for man to make sense out of it, the idea of inert and dull matter is deeply embedded into Western ecologies. Not only did this attitude prove fatal in colonisation of nature, but did trigger the sixth mass extinction, we are currently entering. And it is a critical point to rethink and reimagine our relationship with the natural world, for our own sake.

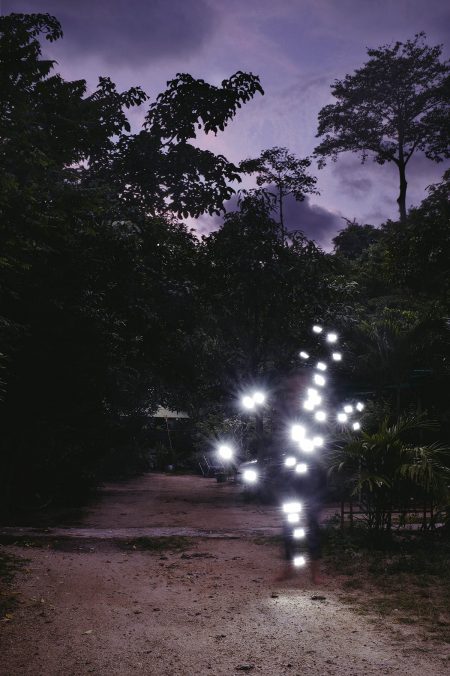

I borrowed the concept of vibrant matter from Jane Bennet’s study Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (1) which seemed to be relevant and important for the discussion around We/re nature. Bennet argues for the agency of matter and evolves on reciprocity between human and non-human bodies merging in ‘a heterogeneous monism’ (2). The very articulation – vibrant – visually matches Ventzislavova’s photographic series with pulsating flashes of light inhabiting the landscapes. The shimmer appears as to manifest the spirit of matter, as to unveil its concealed visceral powers. This metaphor of registering an inner energy of nature enlivens and vitalizes what we used to think raw and passive. I’d say the artist is developing here visual rhetoric for what Bennet advocates in her theory – for acknowledging the inanimate things capable of action and self-expression.

Ventzislavova introduces the lights that visually evoke a narrative resembling both Indigenous cosmologies and sci-fi movies – futuristic and ancient, belonging to technology and spiritual knowledge simultaneously. By this synthesis of visual codes, We/re nature communicates a crucial idea – material turn does not encourage pristine dreams or any reversion, on the contrary – it embraces technology and envisions the positive fusion, but to be based upon new communalities of species, in which diverse non-human actors will be equally included and appreciated.

Borjana Ventzislavova Am Ende bleibt das Licht 02, 2020 © Borjana Ventzislavova

Borjana Ventzislavova Am Ende bleibt das Licht 01, 2020 © Borjana Ventzislavova

Borjana Ventzislavova Am Ende bleibt das Licht 03, 2020 © Borjana Ventzislavova

Borjana Ventzislavova Am Ende bleibt das Licht 03, 2020 © Borjana Ventzislavova

Entering Kunstforum Tresor, you find yourself like in a cave or under the ground – earth brown walls envelop you. One might sensate what Donna Haraway describes as us being part of a huge pile of humus (3). Scattered wood branches, fruits and vegetables fixed on the walls (that might have been rotting and turning into fertilizer). In the corner, there is a fresh mound soil, reminding us about composting – a natural labour of transforming organic life. Ventzislavova draws poetically on the wonderful potency of matter for renewal, regrowing, revival. Consulting Bennet’s text again, I’d compare it to what the scholar calls “to induce in human bodies an aesthetic-affective openness to material vitality”(4).

However, the heart piece of the show is the video We The Nature, in which nature is given a voice and addresses us with a deep emotional speech about inextricable interrelation between the world and human being. Ventzislavova takes the spectators around the globe switching the sceneries between desserts and forests, seas and mountains – the footage had been collected over past 10 years and during the pandemic was edited into the film. Following the flickering lights, we visit beautiful, desolated places – is it a pre-human or post-human situation?

Despite compelling playdoyer, I see an issue here with the very use of language. The artist seeks to deliver a message and chooses the most direct and presumably the most intelligible way – to make nature speak. Although linguistic domain belongs to human mind exclusively. As Karen Barad points out, language has taken power over matter to the extend of mediating and representing it, so we believe language to determine what is real. Thus, liberation from it and practice of different means for connection would resolve in radical performativity (5). By undermining language, eliminating it as filter between us and the world, we can train new receptivity and reimagine our relationship with nature. In this case Borjana seems to contradict herself by making nature anthropomorphic while manifesting its independent vitality. It’d be exciting to encounter genuine self-expression of things, to imagine how it’d sound. Yet, one can argue that We The Nature is a deciphered call of matter, written and read aloud.

Curated by Lisa Ortner-Kreil, the show comes in a dialogue with her previous project Gerhard Richter: Landschaft, in which the curator questioned the status of landscape art within anthropocene. And Ventzislavova’s work continues the research by taking a different perspective, and what I think of extremely importance, beside raising ecological concerns, Borjana is developing new visual language of vital materialism. Without delving into catastrophism but searching for potential move, which is very inspiring. Her intuitive, open, and honest approach, which leaves room for spontaneous gestures, is the one to be fruitful for the “chipping and shredding and layering like a mad gardener, make a much hotter compost pile for still possible pasts, presents, and futures” (6), in Haraway’s words.

Exhibition: Borjana Ventzislavova. We/re nature

Exhibition duration: 24.03. – 27.06.2021

Address and contact:

Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien

Freyung 8, 1010 Wien

www.kunstforumwien.at

(1) Bennett, Jane. Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press, 2010. (2) bid.,121. (3) See Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016. (4) Bennett, x. (5) See Barad, Karen. Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. duke university Press, 2007. (6) Haraway, 57.

About the writer: Liudmila Kirsanova is an independent curator and writer, whose research is focused on autofictions, storytelling, and politics of belonging. In 2019 she became the finalist of the curatorial award Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm. Curating international and domestic projects, Kirsanova has been advocating and promoting female artists, in particular those from non-Western cultures.