Alberto Garutti. A revolution of affections by Roberto Casti

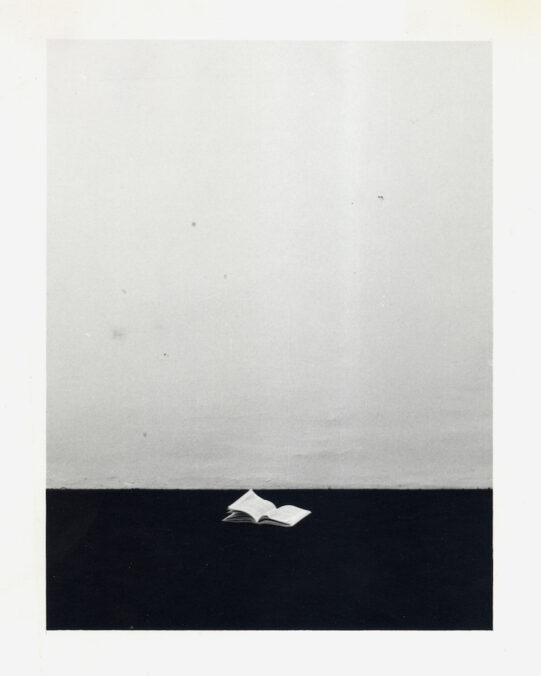

Critique. Alberto Garutti founded his research on the act of looking. However, his looking has never been an explicit attempt to practice a human power on the things and the world. In fact, one of his first photographical works – titled Credo di ricordare (I think I remember) and exhibited for the first time at the Diagramma gallery (Milan) in 1975 – gave importance to objects, making them subjects who inhabited in the living space. Maybe from this mindful and generous act of confrontation and relationship with the surrounding space is born the entire critical approach that has characterized not only Alberto’s artistic research, but also his career in the field of teaching.

And it is precisely inside the Aula 1 of the Academy of Brera in Milan that I had the opportunity to witness his method, a choral and rarely self-referential approach through which a dialogue on the work of art took place. This was the focal point around which all the relationships that constituted it revolved, charging it with meaning. We can therefore say that the very meaning of the course did not lie in the vision of the professor but in the relationship of the people who attended it.

And precisely this dimension of circularity – conveyed by a critical thought that had the core of things at heart, the problems of the contemporary, our own responsibility as artists in the world – constituted the true form of the painting course that Alberto „held“. Perhaps “held” is not the right word because the course fed on itself thanks to the relationship between people and was never shaped by the univocal gaze of the professor: Alberto preferred, in fact, an open pedagogical method, therefore not marked by the imposition of certain directions or solid ideas on how to do or not to be an artist but from the suggestion, reflection and questioning of the work. This approach has led me, like many other people who had the good fortune to have him as a teacher, to throw my person and the surrounding world into crisis, to look at reality as a chain of relationships that need to be highlighted and, once again, discussed, transformed, conveyed by a language.

Alberto Garutti, Credo di ricordare (I think I remeber), 1974, courtesy Fondazione Castellani

And Alberto’s language itself – expressed through installation, sculpture, painting, photography – wasn’t an imposition from above, but a careful caress to objects or subject on which he focused his attention. His landscape was the domestic one that penetrated the natural and vice versa, with the empty spaces of the houses and the lightning of the sky, with the dogs that live in a place and the people who walk beyond the wall.

Being part of his course has meaning being part of a crisis, which is necessarily a personal crisis useful to grow, mature and constantly resignify (sometimes perhaps in an all too pressing way for the head of a twenty-year-old) one’s own person as well as artistic aptitude. But, probably more overwhelmingly, it was a crisis of collective needs. After all, different generations of young artists have emerged from its course and, if this means something, each of these generations has been able to find within itself a common horizon to align with, both for expressive or intellectual affinities and for the need to reflect ourselves in the same crisis of the present, with all its problems on which Alberto invited us to dig and dig.

Alberto Garruti, Teatro di Fabricca Peccioli

Ethics. Alberto’s first public work was born in Peccioli (Tuscany) and is perhaps the one that most simply and comprehensively embodies his sensitivity. Although the decision to restore the Teatro di Fabbrica may seem conceptually straightforward, the operation required four years of work (from 1994 to 1997), not only in terms of design but also in building relationships. From the title Quest’opera è dedicata alle ragazze e ai ragazzi che in questo piccolo teatro si innamorarono (This work is dedicated to the girls and boys who fell in love in this small theater), one can deduce an attention that goes beyond the reconstruction of a building. It positions itself in that space between architecture – the field in which Alberto was trained – and the emotion that moves the people who inhabit a place.

In front of the theater’s entrance, a stone plaque bears the title (or caption) of the work, thus serving as a significant device that bestows a poetic, but above all, ethical aura on the entire restoration operation.

The artist approaching public space, as Alberto used to say, must come down from the pedestal and serve the community. He did just that – he talked to the inhabitants of Peccioli and discovered a common thread, a nostalgic need to restore importance to a place that once represented the birth of human and romantic relationships. This is because a space, in this case, an architectural one, cannot be separated from the relationships that animate it; it is shaped by those relationships. Therefore, the work, in this case, highlights something that is in the background and does so in such a simple way as to appear invisible, especially when compared to the countless monumental works that many artists impose on public spaces, avoiding any active dialogue with the inhabitants. For this reason, Alberto’s approach could be seen as a unique stance compared to the work of many artists who operated in the 1990s. He was one of the few who took on a responsibility. Many artworks present themselves to the public as silent and elitist monoliths that often turn away the gaze of those who do not feel part of the art world.

Alberto’s works, on the other hand, are open; they can speak to both the collector and the passerby who happens to find themselves at the Malpensa train platform in Cadorna.

They are devices of time-space awareness because they involve the viewer at that very moment, regardless of social class or background, cultural baggage, or artistic preferences. They, indeed, invite everyone to activate a sense of awareness. And to achieve this, Alberto never resorted to too many aesthetic or cryptic subterfuges. The work presents itself in all its simplicity, but its strength lies hidden in the powerful and complex network of relationships that unfolds before our eyes when we read a simple inscription: I am here in this moment, and I am living; I can hear the sounds of the city and sense the presence of the people who live beyond me. I remember that at this very moment, a lightning bolt is falling somewhere in the sky, and a new life is being born.

I have never heard Alberto speak about interdependence, but I find myself thinking that such a concept could reflect a condition that underlies his works. This is because it reaffirms that his research managed to distance itself from those self-referential, provocative, or sensationalistic ways – typical of the 1990s and 2000s – of making art.

Alberto Garutti, Che cosa succede nelle stanze quando le persone se ne vanno? (What happens in rooms when the people have left?), Artefiera Bologna, 2023, courtesy BolognaFiere and Emanuele Anselmi – team99Agency

Poetics. This text had been blurry in my mind for months and months, but only now has it gained meaning. Perhaps because night has fallen, and I’ve come to understand that despite people are used to leaving – by nature or necessity – everything continues to live and vibrate. The artist focuses on something that others don’t see, suggesting its presence, and then giving it meaning. It requires starting with a gaze that must always strive to seek wonder, like when we insist on staring at the sun despite our pupils beginning to hurt, or when we experience pleasure and complicity in observing our dog looking back at us while walking beside us.

Taking note of these relationships – protecting them if necessary – and making others understand that they concern everyone. We are part of the landscape, thus we have a responsibility towards it. We are woven into the same network of connections. And art can leverage precisely this aspect, as it has the power to amaze or move countless people to tears. I’m not sure if Alberto’s works can truly speak to everyone, but they certainly manage to do much more than other works where the narcissistic figure of the artist prevails.

An inattentive eye might actually claim that Alberto is not present in his works (unless, of course, we consider his body in the photographic works of the seventies, where he appears). Some might argue that his works are cold and calculated operations aimed at achieving sentimental objectives. But this is not the truth. Alberto was immersed in the network of relationships that led him to create his works; he loved talking to others and even questioning his own visions with us, his assistants. The discussions within the Aula 1 were his lifeblood, and in recent years, he felt their absence keenly. What may appear to be an art reduced to minimal aesthetics, characterized by meticulous formalization and attention to the tiniest details (we can indeed say it presents itself that way), always conceals an imperfection that contributes to setting his works apart from the rigidity of mechanical and serial production. That’s why the backstage of his research is essential, understood both as a moment of exploration in a territory before the realization of a public work and as the true „back“ of an artwork. The „Orizzonti“ (Horizons) works are dry and simple on the front, yet rich with writings and fingerprints on the back. The front is a continuous line from glass to glass, while the backside is always different; it is the surface on which Alberto wrote the names of the people to whom the works are dedicated (the ideal horizon of his life).

Art tends toward perfection and, therefore, it is always imperfect. This is what he used to say to explain the artist’s attempt to go further and always seek the work that functions perfectly. However, the essence of art, I have learned during the recent years working with him, lies precisely in that imperfection from which we try to escape. In reality, art touches us because it reminds us of our vulnerabilities, highlighting our precariousness. Imperfection makes the artwork authentic; it makes it more human. After all, we are part of the landscape, and it will continue to live even in our absence, even when we can no longer exercise our gaze. But art will only exist as long as we are alive. It will exist as long as there is even just one person searching for meaning in the world, in relationships, and in things.

Alberto paid great attention to things; he had a different perspective, a unique sensitivity. Everything had the potential to become artwork in his presence: from car trips accompanied by classical music to the sharp light that divided his studio during sunset.

Then, simply, you would realize that you were looking at reality, but you had never seen it that way before. And this is also reality, the one in which his works continue to live even though he is no longer with us. It will still be dark for a few more hours, and everything feels strange. However, those works vibrate, they speak to us despite everything. They are the first works by Alberto that I got to know and also the ones I prefer, perhaps because during the day, they seem invisible, but at night, they come alive. Just like fireflies, which I had never seen in my entire life until the day I received the news. An artist, according to Alberto, must have a critical, ethical, and poetic attitude. Poetry remains the ultimate aspect, as it is the most important element that defines art, making it human and emotional, rich with relationships. After all, we have an infinite need for people to care for; it is the only way we can share our vulnerabilities and connect with one another.

*This text was first published on the Italian art magazine Exibart on July 9th. It was two weeks after Alberto Garutti died. One of the most influential and unique Italian artists has passed away at the age of 75, after a long and significant career in the field of teaching and public art.

Roberto Casti is an artist, musician and writer. He lives and works between Milan and Iglesias, in Sardinia. His artistic research includes various mediums such as video, performance, installation, painting, and sound. With the transdisciplinary project „The Boys and Kifer,“ which originated in 2014 as a fictional music band, he explores new methods of community and coexistence through the participation of numerous artists, musicians, and theorists.