Where will the Albanian Pavilion be located?

The Albanian Pavilion is located at Arsenale Artiglierie. The pavilion’s architecture was realized by German architect Johanna Meyer-Grobrügge, which is an essential part of the display. She takes in consideration transparency and receptivity, elements that resonate with the work of Lumturi. As part of the presentation and in collaboration with British interactive media artist Alexander Walmsley, we have also created an interactive virtual archive under the title “Lumturi Blloshmi. A Personal Geography” where the viewer has the possibility to explore the working and living environment of Blloshmi. Eni Derhemi is the assistant curator and production manager for this project, a close collaborator of mine for some years, and I want to thank her and all the team for the amazing support.

How has Blloshmi been perceived by fellow artists of her time and then by critics? Specifically I am interested in the period of time when the artist began to push boundaries and experiment with combinations of materials and media. I remember how struck I was while visiting your curated booth “Focus: Ex-Yugoslavia and Albania“ at Vienna Contemporary in the year 2016, and seeing, among others, the work of Blloshmi.

Lumturi, and other artists from Albania during this time were looking forward to the changes brought about by the 90s and the end of dictatorship. This new era brought a lot of hopes but as well a lot of confrontation with the changed reality. Given that Blloshimi did not get married and was dedicated fully to her art, she had to continuously fight for and claim her position within the professional art scene that was dominated by men. In a photograph from the early 90s, we see what was then called „The group of independent Albanian artists“ where Blloshmi is the only woman. We can say that she was well received from colleagues and critiques, but not because they were receptive but because she claimed her place and her position following her own discourse, intuition and expression necessities. She started experimenting with the medium of painting by introducing other materials into the canvas – fabric, everyday objects, or other materials that she needed to achieve a relief and give paintings dimensionality.

Compared to other artists of her generation, she manages to reinvent herself. The basis of her work remains a conceptual intention, mixed with intuition and diligent application of her creative energy.

At the end of the 90s, Blloshmi started photographing and found a new dimension for her artistic expression. While she had already begun to break with the two-dimensionality of the canvas while always being aware of keeping the subject, she started realizing that she herself had always been part of her work. In 2003 she had her first official performance at the National Gallery of Arts in Albania. In addition, around this time in Tirana the contemporary art scene had become more vibrant, starting with the first Tirana Biennale in 1999 and significantly developing from there. Although we see Lumturi active and part of national and international exhibitions, compared to what was going on simultaneously, at the same time we understand that the recognition she got remained peripheral. We must also consider that she was a person with a diversity, even though she would never treat herself as such or accept being treated as such by others, and needed much more mediation than others. Although she stands out among the artists of her generation, she did not have the full recognition and support from the new generation of curators and organizers that were more focused on younger artists or on bringing international artists to Albania.

Today, I observe that many contemporary galleries are trying to represent both emerging artists alongside artists of older generations who have been underrepresented. I’m thinking of Tiziana di Caro Gallery (Naples), which has brought the partly unseen qualities and groundbreaking creative processes of artists such as Tomaso Binga, Betty Danon, and Simona Weller to the public’s attention. Also the work of German gallerist Tobias Posselt (Galerie kajetan, Berlin) which is resurfacing the work of artists such as Erich Reusch or Claude Viallat. What is your approach to bringing Lumturi Blloshmi into the contemporary discourse and what would you like to achieve for her legacy?

Today we have all sorts of artists and personally, I find artists that create out of an inner urge, or see the creative process as almost a mission to transmit a larger experience or perception really interesting. Some of these artists have worked independently from the art world, no matter the conditions. I find it interesting to see and explore their works even after so many years because they inherit something valuable independently from a specific time and space. The artists who are doing this kind of work know with what they are dealing and they know they are contributing to a higher and larger cause or discourse, they get their satisfaction by completing their “task” at the moment, by giving immediate meaning to their existence and that is priceless. Blloshmi was one of those artists and that gave her a particular assurance that she was on the right path doing the right thing.

She understood as well that it was her duty to make her work visible and accessible, and it is our duty (as curators, art historians, galleries etc.) to preserve these kinds of works, to make them public and to mediate so that the viewer can experience and interact with their inherited values. I believe that valuable and meaningful art sooner or later will make its way into the public.

Blloshmi is an artist of international importance, so I would love for some of her works to be placed in significant collections in international museums worldwide. It was Lumturi’s biggest dream to have a museum dedicated to her works and I hope with additional support to be able to realize this and to give this incredible gift to the art world and the public. The artist never wanted to leave Albania and move somewhere else. She was intricately related to the Albanian reality, which she hated and loved at the same time. It would be great to have a museum of her works in Albania so that a new generation of artists can get to know the work and life of Blloshmi.

In addition to a long artistic career and a vast legacy that the artist left behind, which certainly speaks in numerous words, are there also people who have significantly assisted you in exploring further the artistic work of Blloshmi?

Of great support has been the family of the artist, especially her nephew, Ervin Blloshmi who also studied painting at the Art Academy in Albania and with whom the artist had a very strong connection. It is fortuitous that the artist’s family understands the importance of her work and is willing to share it further. I have also been meeting and working with close collaborators and friends of Lumturi – writer and artist Rudi Erebara, photographer Albes Fusha, writer publisher and curator Krenar Zejno, art researcher and curator Suzana Varvarica, art scholar Eleni Laperi and choreographer Gjergj Prevazi. All these professionals have been collaborating with Lumturi and have continuously supported her in her career and I am very happy that they have been contributing with their knowledge in this undertaking. I must emphasize that this exhibition is very important because it is the first time that Albania is being represented by a female artist with a solo presentation in Venice. In addition, I am the first female Albanian curator to curate the pavilion. I think it is important to mention that this representation was welcomed and supported by the Albanian Culture Ministry which marks as well an important change toward a progressive and equality-based cultural policy.

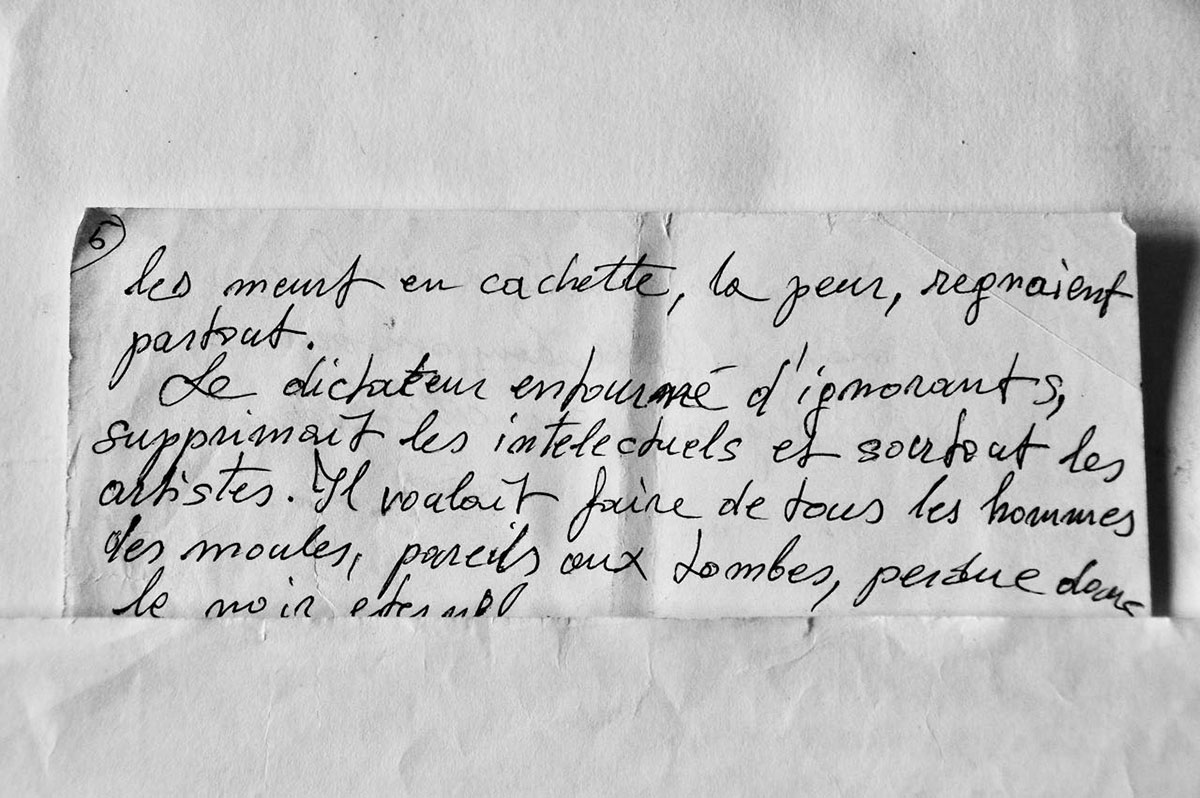

But most of all of great assistance to me has been Lumturi herself. She has left a rich archive of letters, notes, photographs, articles, and artwork. In order to fully be able to disclose it and to make it accessible to the public, I would need to spend more time with these materials, which I hope to be able to continue after the end of the Venice Biennale.

While researching for this interview, the Berlin-based artist Christine Sun Kim came to my mind – her ongoing process of trying to be understood and finding new ways of artistic communication as a deaf individual (e.g. using A.S.L, learning D.G.S, using charts, text and drawings). Which tools did Lumturi Blloshmi chose for communicating and participating in the art discourse?

Blloshmi wanted to become a dancer, so music played an important role for her from an early age. However, at the age of five she lost her hearing following a bout of meningitis, from which she miraculously survived. After recovering, Blloshmi lost her ability to speak, however her mother decided to still enroll her in a general school. The elementary school teacher, Evanti Ciko, patiently teached her how to dare to talk again. Blloshmi never learned sign language, but instead learned to read lips and to verbally communicate with everyone. Although she preferred to have friends around that would mediate in case she needed it, she would go everywhere alone. In addition, writing played an essential role in her life. In situations where I discussed something important with her, she requested to have a written statement or confirmation. Through this process of writing, her archive is very rich with notes, letters and correspondences. But of course, her disability made it even more difficult for her to be present, to penetrate and be present in the art and drive her own discourse. However, her true voice was her body, the way she moved and the way she embodied her energy. This embodiment characterizes her works as well, which go beyond form and thought and draw a directed path to the viewer who is invited to experience “new emotions” as Lumturi would describe them. It seems to me like each of her works talks, or better to say resonates, and that is a powerful characteristic because that which has the ability to communicate without language, has the potential to interact beyond time and place.

Indeed, Lumturi was very aware of this and she realized that a part of her existence went beyond time and space and I feel that a lot of her work captures this perception. The body plays a very important role to her. She understood that her (or the) body is a tool, a container, so she aimed at getting total possession of the body and form by fully animating it.

You have been working with the Mexican filmmaker Tin Dirdamal on a documentary about the artist’s life. What is the story behind this collaboration?

I wanted to do this experimental documentary some years ago when Lumturi was still alive, unfortunately I didn’t get the funding that I had applied for. However, it now looks like I have the possibility to realize this vision for the pavilion. Of course this project does come with its own difficulties as Lumturi is not here with us anymore and Tin Dirdamal has never met her. However, Tin has a way of working which I really appreciate. His films are poetic, based on introspection, and he has an interest for what is hidden or appears unknown. He has an individual approach that consists of not leaving out his presence in what he is trying to capture. This is often an element that I miss in artwork and films and is of a strong relevance to me personally. The film we are working on will capture elements and relevant details from Lumturi’s life, intending to record some of the moods, tonalities and expressions that made her. It takes as a starting point the now, and is done keeping in mind a future viewer who did not know Blloshmi, and which will discover her step by step with the filmmaker. It is, in a way, a co-work made of notes and thoughts by Lumturi and new recordings in places and situations that meant something to the artist. Our intention is to capture what might represent and transmit her presence. At the same time, the film will also provide a direct biographical link to the artist, which will allow the viewer to develop a feeling for the person and not just the artwork.

Address and contact:

Albanian Pavilion

Arsenale Artiglierie, Sestiere Castello

Campo Della Tana 2169/F 30122 Venice

www.albanianpavilion2022.com

Adela Demetja is a curator born in Tirana, living and working between Frankfurt am Main and Tirana. She holds a master’s degree in „Curatorial and Critical Studies“ from Städelschule and Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. She is the director of Tirana Art Lab – Center for Contemporary Art, an independent art institution which she established in 2010. As an independent curator she has organized and curated numerous international exhibitions in Europe and the US. Demetja became friends with Blloshmi in 2016 and became one of her close collaborators until the end of her life.

Erka Shalari (*1988, Tirana) is a Vienna-based art author. She focuses on discovering unique artistic positions, unconventional exhibition spaces, and galleries that have deliberately broken new ground in their working methods. She relies on unorthodox publishing practices, coupling these with a nonchalant manner of writing. Her work oscillates between articles for magazines, exhibition texts and press releases – https://linktr.ee/erkashalari