Erka Shalari: Is there a question you keep asking yourself in your creative work?

Flaka Haliti: When a failure and success appear at the same time, on the same matter throughout the process. When I say matter I mean both as ´material´ in object or as an ´issue´ in a subject. A matter that could generate potentiality but also can be an obstacle to opening up new possibilities in the process of attaining transformation. Feels like anything, including nothing. The change that is about to happen, or the change that is not going to happen. It doesn’t generate on your own, but in the wake of a person, an object, project, concept or scene, as a kind of twisted notion of potentiality. Which, I find productive and challenging when it happens in the creative process.

In your work, you address both abrogation and appropriation. I wonder how the dialogue between these two acts look.

It is materialized as a double agent throughout the theoretical and aesthetic language. On a visual level, it is the way I work with materials, the relation I make between two opposed categories, that equally pulls back. Moreover, how the readymade and abstraction are put in counter-dialogue. The relation between the familiar and the alien as such –– what makes the uncanniness, enstragment and in theory is the way my entire practice basically operates and detours in the larger system. Since abrogation is the refusal to adapt to systematic order, while appropriation makes adaptation of it. In my practice, they meet in the middle and together they open up a dialectical field when new aesthetics, semiotics and possibilities emerge and start to make sense. And basically, where opacity gets entangled.

How do your artistic themes emerge and how do they relate to current crises?

Since last 10 years my main preoccupation in my artistic practice revolves around the politics of disidentification (Jose Esteban Munoz), displacement, and in-betweenness as ethical and socio-political necessities. As our times are loaded with contradictions, clashes, and inhuman discriminations, I try to investigate how agency and integrity are produced or lost in such regimes of paradoxicality and violence. Through the formation of particular shapes and figures and their inner logic and dynamics, I try to speak about such concerns on a larger plane. In an attempt to create flux between the micro and macro scales of disidentification and in-betweenness at work within my practice, different topics are tackled: such as belonging, subjectivity, the human-animal relationship, migration, demilitarization, territorial boundaries, and powers like national borders, or the dispositions of associations like the UN or the European Union and as a Western powers, are brought to negotiation.

However, a crucial question appears when I try to draw parallel lines on questions between how we constitute nation building identities and how the art world at the same time continues to produce still values based on clearly defined identity markers, meaning on practices that are identified or grasped easily by the canon. So as my work enters the public sphere while presenting or stressing the agency of an undefined package: the question is can the public and its institutions operate under such terms? Is it possible for institutions to artistically and politically embrace such issues without undermining or compromising their commodities, if the practice is not purely defined or grasped?

Today, for example, many exhibition texts, mission statements, or press releases promote a more inclusive world of representation by using notions such as fluidity, opacity, ambiguity, and hybridity, to name a few. By bringing those terms forward, they try to resist or oppose normative relational systems. At the same time, contradiction to it is that the same institutions still operate through a cultural understanding of art history, which is mostly based on absolute definition, legibility, comprehension, and labels.

Often a practice is grasped by curators, gallerists, and collectors when it is defined enough, captured, and understood as the artist repeats and constructs a continuous visual style or subject matter that later happens to present itself as absolute claim, which in my practice I try to avoid at any cost. As an artist, I am thus really concerned with what kind of political forms, shapes, patterns, sustainable aesthetics, and languages must be brought into being to guarantee collective continuances that challenge values made in linearity with only and one art historical canon.

When gazing at your works, a lot of questions occur, especially in terms of how the work is born. Can you tell us something about WHOSE BONES, which you created for Steierischer Herbst, included now also in your solo show in Cukrarna?

In the 2020 pandemic lockdowns, the outdoors were the only opportunity to hang out. And with museums and galleries all closed, public art sculpture gained different attention and recognition by being excessive. Meanwhile, BLM movement culminated when many statues and monuments of a dark colonial history were removed. And I remember there was very big snow in Munich in March 2020 when I started paying attention to outdoor sculptures and monuments. How the snow becomes an active actor by covering the sculpture partly, shaping the sculpture or ridiculing the statues, or the monuments of national importance.

Following questions of in-betweenness as a new agency that can constitute identity construction, made me question how many monuments of national and state symbols are represented through heraldry animals‘ coats of arms. And how often one alpha animal symbolically represents different countries, like an Eagle, Tiger, and so on. No matter how much they try to distinguish their visual representation throughout their design by constructing different narratives, at the end no matter what, the eagle still remains an Eagle for each country that uses that as a symbol. With „WHOSE BONES“ artwork – I reconstruct the skeleton of an indeterminable animal used in heraldry, in particular in the coat of arms mixed with the bones of another ordinary animal, the lowest in the hierarchy of living creatures. Fusing the difference between the bones of the noble panther from those of the sordid cat.

So, as a result, I create this futuristic chimera creature that combines domesticity and danger, the high and the lowly, the colonizer and the colonized, the predator or the prey, those suggesting again in-betweenness, a form of existence what should be crucial to our time—in which qualities that used to distinguish and create dichotomous no longer apply absolutely.

Additionally, the white element of snow covering the inscrutable feline of the mixed bones emphasizes the layer of ambivalence, and it simulates what the sculpture would look like outdoors from the snowfall as a result of drastic climate change.

What do you think about dichotomies?

Dichotomies are inevitable, I guess – but I try to resist or refuse to acknowledge them when dichotomies become hermetic and as such, sovereign, as a stand guard over right and representation. It is the 21st century and I believe it is time to acknowledge the in-betweenness as a new social form of political entity with its full affordness.

If we look back, what helped you develop your artistic voice?

Living between different cities, cultures as western and non-western, having different art education from more traditional like Prishtina one, to those more progressive like Städelschule Frankfurt, have all shaped my practice, yet I think the Ph.D. studies at Vienna Academy has been the culmination of giving me a clear voice, no matter how disturbingly, disidentified and confusing my practice might still look from outside. I have learned how to be misunderstood as a subaltern position and still find its way over representation in this system.

You work a lot with large format works, which I presume also need an assisting team. Can you tell us something about how the works materialise in your case?

I start with hand and Photoshop sketches back and forth, scan, collage, draw spray on top, which later becomes a digital file again, either 2D or 3D, when then designers and architects are involved in my studio team. From there we do tests or prototypes, then partly gets to be produced in my studio and a lot goes for manufacturing, it depends. Sometimes the final result of a big-scale artwork is seen when all the pieces come together with the final moment of installing in the place. At that point, there is no space for any mistake. It is risky as it sounds, but those are the most joyful moments in my production when I see and I feel relieved that the installation it’s working the way I was planning and imagining visually, and was hoping to turn out.

Do you think that the site-specific approach has been shifting over the course of years?

Well, in my understanding, the pure abstract form and so-called neutral space are never innocent. Even the White Cube has never been neutral. Every given space or form is not only historically charged with meaning but further animated by its interrelations –– the movements within and around it, as well as the perceived differences depending on our individual backgrounds and the location we have in question. From this point, I guess any space can be easily site-specifically approached, but it always depends, what level of depth is brought forward. However, it is important that the modes of quality that frames the production should come from aesthetics, conceptual and political strategies that operate as an agency towards spatial site-specific relations and not conditions as such.

Markus Miessen sums up in a text about your work as follows: „At the end of the day, Haliti’s practice is also about writing titles“. Is it like that?

YES, and NO. That statement of Markus Miessen on my work – as much as it stands, also it doesn’t. This has a lot to do with the way I treat the entire body of the artwork by breaking hierarchical order, of each element – decentering its constitutive central, as a constant shift of positions. For Markus, my work starts with titles, for someone else – I know – is my scale and aesthetics spatial presence. And for many the larger picture is the theory and conceptual framework that I choose to unfold clearly through lectures and public talks as a zoom out.

What constitutes the artwork in my practice is the relation between each element: title, form and content as such that altogether forms a non-hierarchical relation when different elements presented as total-whole, break the opposition between center and marginals, which in my understanding should follow the logic of Poetic of Relation introduced by E. Glissant. For him, this kind of totality – as whole – is opposite of totalitarian that would translate as one unit, however, the total needs the presence of a whole equal elements „in artwork“ in order to become a whole. Each different element i.e. title this case forms a relation by always moving on from itself – from the center. So yes, there is a moment where titles seem to hold a centric position in my work, yet in another artwork, it doesn’t have that dominant presence, it moves from itself. Cuz, I believe even the artwork as an entity should be able to dissolve its center point from itself.

I would like to talk with you also about teaching, recently it has happened to me to meet students of yours. In 2022, you were leading a class on Eco Criticism in Salzburger Sommerakademie, now you are teaching at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. How does teaching feel, and what is important for you in this process?

Love teaching, but it’s tough. I haven’t yet found a good way to save myself while doing it (smiles). However, my main investment in education is focusing on placing hybridity as a social-political form that can break the systematic normative order also at the organizational academic level of acceptance. I feel there is still so much to do in art education in relation to the classical authoritative order of how chair departments are represented.

Right now, there is a general academic urge to support or establish hybrid classes, yet I think the core of the problem is often missed to be addressed since in order to challenge the traditional division of media and department, one also needs to challenge identity politics as I said above overall within art history. With my students last semester, we have been reading Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network by Caroline Levine (part of my PhD research reading list too). She questions „affordances“ of four major forms—wholes, rhythms, hierarchies, and networks––and argues that forms organize not only works of art, but also political life—and our attempts to know both art and politics is through recognizing how those forms manifest themselves. Our life experience is certainly shaped by the power of some disturbingly repeated forms, which is not very different in academic and pedagogical systems too.

What kind of changes do you feel when revisiting Prishtina? How do you see Manifesta’s role in the city?

In 2022, I visited Prishtina 6 times, and many times stayed for two weeks because of work. I haven’t spent this amount of time since I left the country in 2008. I have to admit it did smth to me. I fell in love again with the vibe, people and many things. Part of this has to do a lot with what Manifesta brought in. It was a very successful edition, with an amazing program curated very carefully, generously and thoughtful by Catherine Nichols.

Many old public venues were reactivated and revitalized. City felt bigger. The post-pandemic thriving moment played an extra role too, in combination with Gen Z timing bringing new energy in urban and cultural life. This marks a certain particularity in Kosovo since we are talking about the most isolated country in Europe. And it’s Gen Z is the first generation that grew up with unlimited global virtual connectivity. Their limitations and isolation of not being able to travel might translate the lifestyle slightly differently because of the internet.

Overall it’s an exciting moment for Kosovo; we have a new configuration in government of a political class that entered power in 2020. A shift that feels more to go towards citizens‘ communities-oriented power. There is a concrete sense of hope growing (E. Bloch). However, as someone who has lived and been mostly educated abroad – when it comes to my work – I ask myself how much of my perceptive observation on the country can still be considered „a distant view.“ Such as critical distance and critical proximity – when one is very close to its research subject. How long my views are fresh upon my days of arrival and how quickly my wow’s and amazement evaporates becomes immune to „another normality“ yet in other ways familiar to me. How do those critical standpoint influences my work and my contemplation?

Rooftops, your works fit very well with such architectures. Thinking here the installation this year at MANIFESTA. What memories do you connect with such structures? How does your work dialogue with the Palace of Youth and all the surroundings?

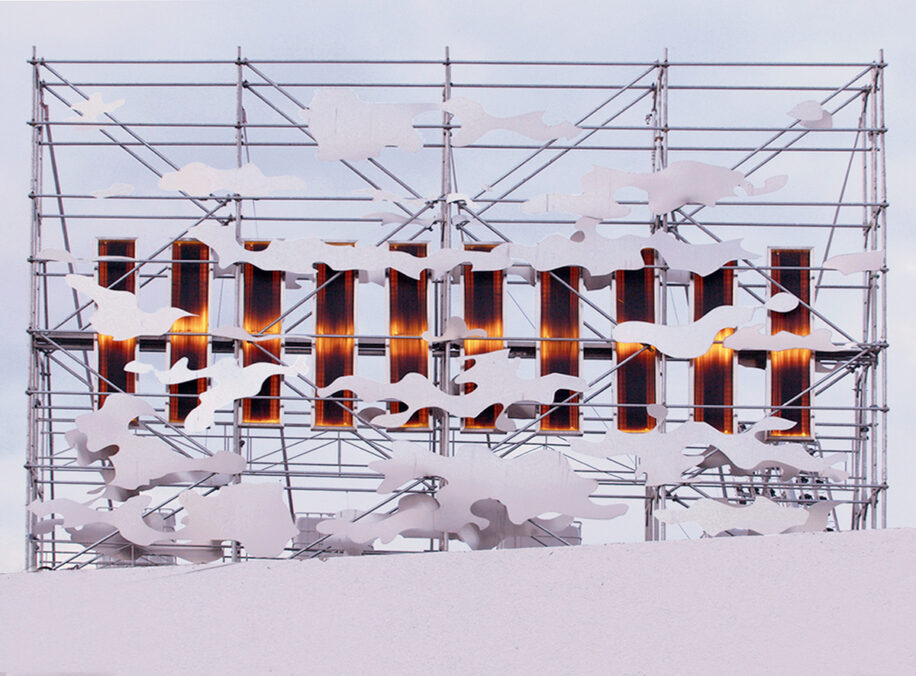

Finding the right location for my work in MANIFESTA14 was not an easy process since it needed to have a sky or distant view of the horizon that enters as an interplay background within a frame of the artwork. Sadly Prishtina as a city doesn’t give many choices, due to all the boom of illegal constructions that transformed and suffocated the city after the war. The Palace of Youth was one of the last locations we considered. It was not my first choice since I was highly concerned to what degree any artwork can enter into dialogue with such a monumental historical building without dismissing the courtesy of its iconic visual appearance and at the same time not be eaten by it. To what degree this kind of visual dialogue is possible and can be regarded as respectful from both sides, especially knowing now that the artwork stayed for a year longer on display with the request of the Ministry of Culture.

Can you further discuss this work in more detail and I’d also like to explore with you your unremitting series of works that deals with „Demilitarisation of Aesthetics“ – I have never encountered this term in such a compound before you.

Maybe because ‚Demilitarisation of Aesthetics‘ as it seems is a term I brought forward 10 years ago through my methodology of research that has since tried to articulate, break through, what it means to materialize, execute such an aesthetic regime within an artistic practice. So with the background I come from, as someone who experienced war and postwar social transitions, demilitarisation of aesthetics became a departing point on my PhD research since 2013. Kosovo doesn’t have its military armed forces yet. After the request was made, I think in 2017, it officially entered that process in 2018 and it’s expected to take up to 10 years until the mission is completed. After the war, up to 50,000 NATO military troops entered the country.

Spatially we can try to imagine the scale of military presence that dominated local landscape, from soldiers, vehicles, compounds, camps, logistic hubs, headquarters, checkpoints etc. Their material footprints covered large territories. Right now, it is estimated that less than 5.000 NATO soldiers are present. As with some of my previous works, I was quite interested in relation to critical questions about the transnational versus national politics of representation in Kosovo.

And how that shaped the national state building new identity. Besides the gesture of demilitarizing aesthetics as crucial research, I’m interested also on “do no harm” policy that comes as a question when it is about looking at the environment impact of sustained peaceful mission of NATO and UN organisations. What is left behind?

From here the appropriation and re-arrangement as an artistic practice continues as I take discarded plastic window panels from the NATO-KFOR german camp in Kosovo, now home of culture institution Autostrada Biennial in Prizren. Though, by activating the object in relation to new contemporary spatial information of what is present –– within the power of imagination or abstraction –– our perception changes towards military object, as a way of overcoming or rethinking the history that is charged with it. In the course of more than 20 years, these plastic panels –– which I used for my artwork commissioned for MANIFESTA14 –– were used previously in military camps. They were burned by the sun, while it formed some kind of wavelength of horizon color effect. That’s where basically my intriguing moment started. Thinking how this enigmatic process has inscribed itself in material, has left magic traces as a witness of time that passed by.

Yet a “non-being object, present but still doesn’t exist in a present tense”, which is how J.E. Munoz describes potentiality. Perhaps it’s haunted by the spectre of something, carrying a story, left to be told.

Under the Sun – Explain What Happened, as poetic as the title sounds, it’s still formed as an interrogative question, which makes another relation to the military. With a massive installation that is placed outdoors at the Palace of Youth in Prishtina, I intend to form an uncanny horizon as a sunset or sunrise against the sky that glows or burns slowly. Put in contrast together with the cut-out (metal shapes) patterns taken from military camouflage, that alone forms a radiance of clouds at the edge of sky, stimulating imagination as an abstraction of how things could be otherwise.

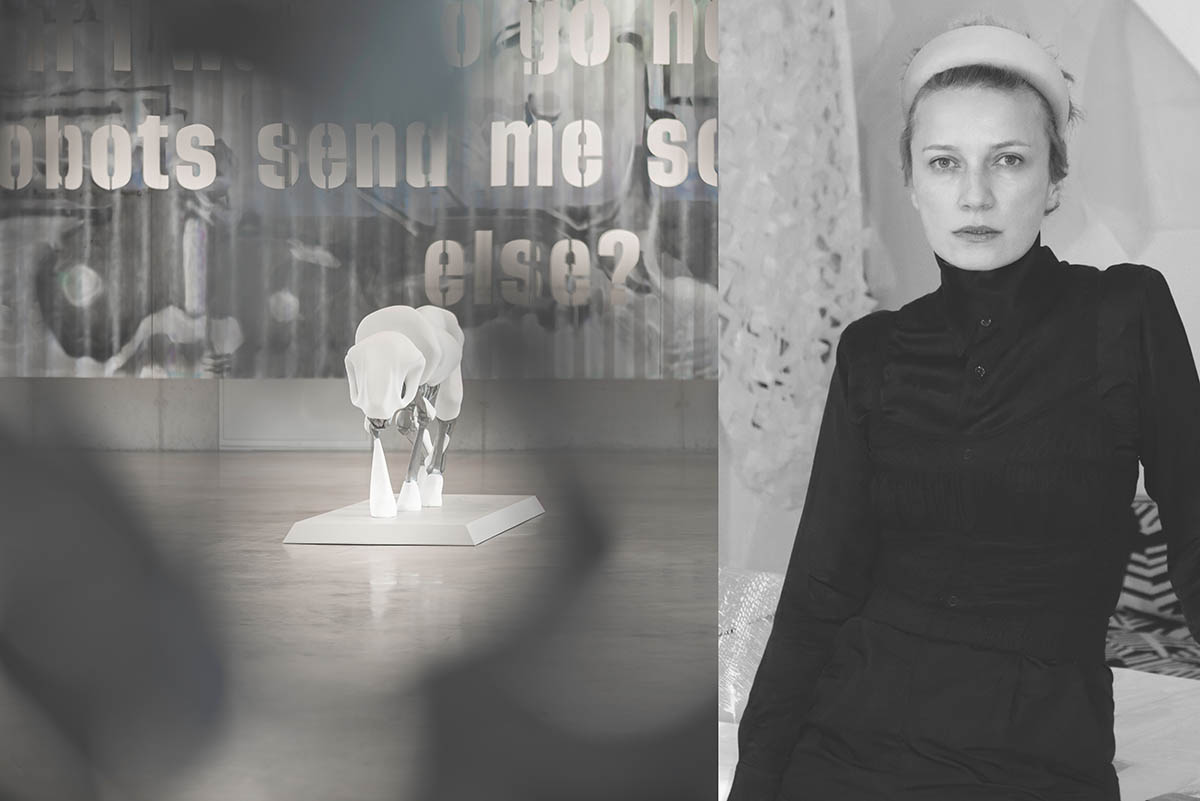

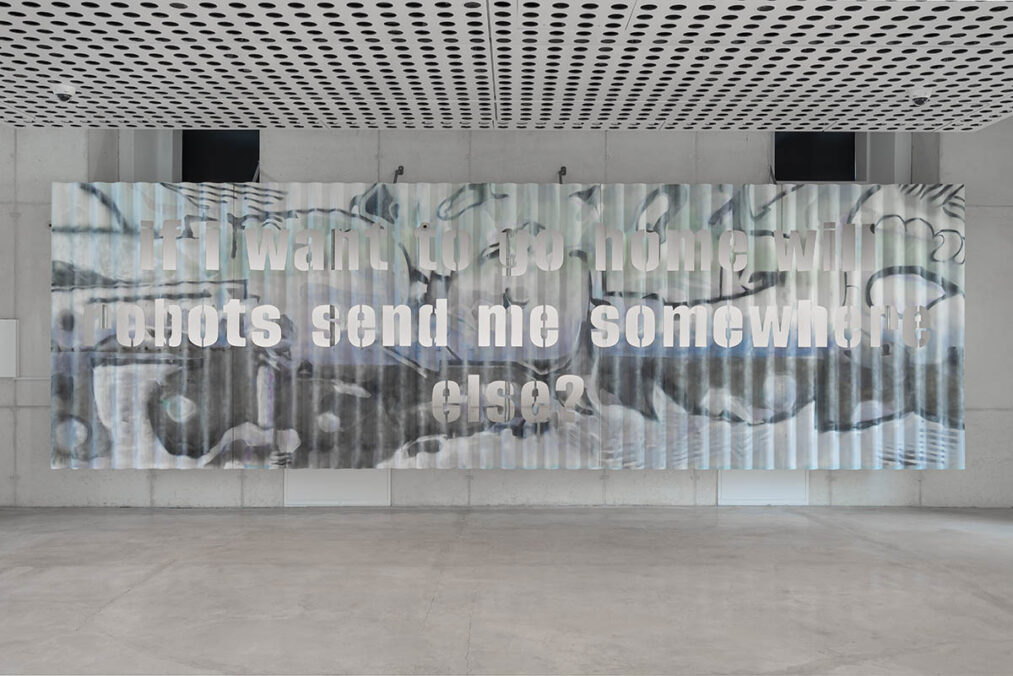

There is also another work of yours that strongly touches me – „If I Want to Go Home Will Robots Send Me Somewhere Else?“.

If I Want to Go Home Will Robots Send Me Somewhere Else? is the curious but also delirious question posed on this large billboard that was installed and commissioned temporarily at Ostend’s railway station in Belgium as part of Endless Express exhibition, curated by Caroline Dumalin. Now it is included in my solo show in Cukrarna, as an indoor installation. Cuts in the corrugated steel plates — reminiscent of shipping containers — if outdoors enable again the viewer to see the changing sky behind the letters. So I drew the title from the „true or false“ section of an online platform called „#rumours about Germany – facts for migrants“. On this website, one can find answers to questions that were supposedly submitted by asylum seekers.

Taken from the website the one I use here altered version, the word „robots“ replaces „Germany“ and „I“ replaces „you“ — a play on words that conveys a split sense of technological optimism and the uncertainty of the self in a machine-led future, beyond the control of human-dictated territories and borders. However, robots in my work often are treated similarly to the Ghost’s urgency. As a kind of retro device reminder from the past that can produce a state of suspension in relation to historically situated struggles. As liminal crossover space between past and present. Their look appears dystopic, but I consider them more as a heterotopic force that at the same time stimulates certain potentiality that is collectively actualized, a sense of what is not yet but in the process of becoming. Sort of abstract understanding of queer horizons.

I find it super intriguing that many works that we have been talking about in this conversation, are part of your Cukrarna show „I SHOUT, YOUR ECHOES BOUNCE, WHAT AM I?“ I would like to use this moment also to say thank you for sharing with me important moments of the Cukrarna History. How has been to work with such a sight?

There are three artworks in the show and one extra element as unknown or undefined piece, of military net, that is less of an artwork and more than a spatial prop. The show title comes from newly commissioned work for this show, the series of 6 bats called: I Shout, Your Echoes Bounce, What Am I? (2023). I created this title in the form of a Riddle. As I grew up in Kosovo, in school books, we often had a riddle to solve from a lesson. The origin of Riddle comes from an Old English word meaning simply „opinion“ or „conjecture“ that is related to a verb meaning „to interpret.“ … so a question or statement that offers a puzzle to be solved. Which is considered 4,000 years old –– ancient form of learning and entertainment, originating from the Middle East. What intrigues me about riddles is about deceiving, tricking, yet it becomes an agent of gatekeeper, solving an answer as password/entry to other worlds, or to a promised land.

So, I Shout, Your Echoes Bounce, What am I? as riddle makes a direct reference to Bats as an animal that is known for its echolocation skills. Bats orientate themselves through an echo that bounces back at them after a shout they make. Thus communication becomes an exchange of resonance and dissolves the ‚who‘ into ‚what‘, into the world environment, meaning what constitutes an entity depends on the relations to other entities. Lefebvre would say the rhythm analises. Understanding of space (…) moving around, as one navigates the space, understanding that which is founded in space influences your body as you negotiate that space.

Moreover, the painting of the 6 bats in the show has a snake around, wrapped like trapping the bat. Snakes are a well-known predator to Bats. So what happens when a bat and a snake become one hybrid creature, maybe a bat and a snake engulfed in the destiny of becoming a dragon?! Not a BAT not a SNAKE anymore, but a combination of both, therefore maybe more.

So the answer to the riddle ‘what am i’ at the end is not clear if it still remains a Bat or becomes a Dragon.

Moreover, as the snake veils throughout bats body, suggests some kind of magic, an iluminal moment of “Disney“ transformation, since bats paint ed texture is flaky as if it’s also dissipating. Both bats and snakes hang from the ceiling, entangled in its formation of becoming maybe a dragon. A kind of futuristic scenario, yet dystopian in its suspense, leaving an assumption what if everything in a plot unfreezes, would that change the course of what is about to happen next? Opening to the unimaginable. Suspense, in novels, movies or theatre is described as a moment of tension (something unexpected might happen) but the interesting point is that the viewer, or the reader is alarmed already and has imagination about the theory of what might come next even if the actors in a plot still act normal. As a result, the whole show becomes an echo of an imaginary space, sacred in its symmetry between verticality and horizontality, occupied by ambiguous entities whose purpose is settled to function and be utilized by the in-betweenes as agency. Thus inhabiting a space of Cukrarnas(former sugar factory, or soldiers‘ barracks during wars) building that in past decades used to also be a temporary home of people on the margins of society. The mystery of the riddle transcends its history, between past and future legends lived and echoed there.

*Editor’s note: Flaka Haliti’s work can be seen currently at Cukrarna Gallery (Ljubljana); Hamburger Bahnhof (Berlin), and MANIFESTA 2022 (extended display till the year end in Prishtina).

Flaka Haliti – www.instagram.com/flakahaliti