The first time that I saw Imaginaciones, my encounter dug up my own prejudices, giving me critical insight about my own cultural background, but not much insight into the art. To appreciate Mexico’s radical queer imagination—and to get closer to my crush—I needed to see the exhibit again. And I recommend that international visitors also see the show several times.

Understandably, Mexicans often complain that foreigners misapprehend Mexican culture. And as I toured through the exhibition, I drafted a list of sassy complaints (about the rather negligible treatment of HIV/AIDS art; the excess of sexualized images of penises and naked cis-men; the insistence upon defining sex and gender with Westerns terms like “gay” and “lesbian,” at the expense of the Mexican vocabulary of putos, mayates, lenchas; and especially the overabundance of photographic and painterly portraits and the relative lack of works in more experimental genres).

I suspected that the exhibition—hosted by a museum of “Modern” art—was hampered by a naïve, institutional investment in modernity and Modernism. The Museo de Arte Moderno—operated by the Mexican government—is a vestige of Mexico’s one- party national-socialist dictatorship, which, throughout the twentieth-century, sought to “modernize” Mexico (often by constructing museums).

Recently, Mexico has taken a more neo-liberal turn. And Mexican “modernity” has structurally readjusted, promising to admit queer identities into a liberal politics of representation.

The overabundance of portraits in Imaginaciones seemed aimed to help straight viewers feel comfortable with queer faces. Conforming to Western standards of canonicity—i.e., to art forms that are easily accommodated by museums—these images largely assent to a politics of inclusion (that is liberal, not radical).

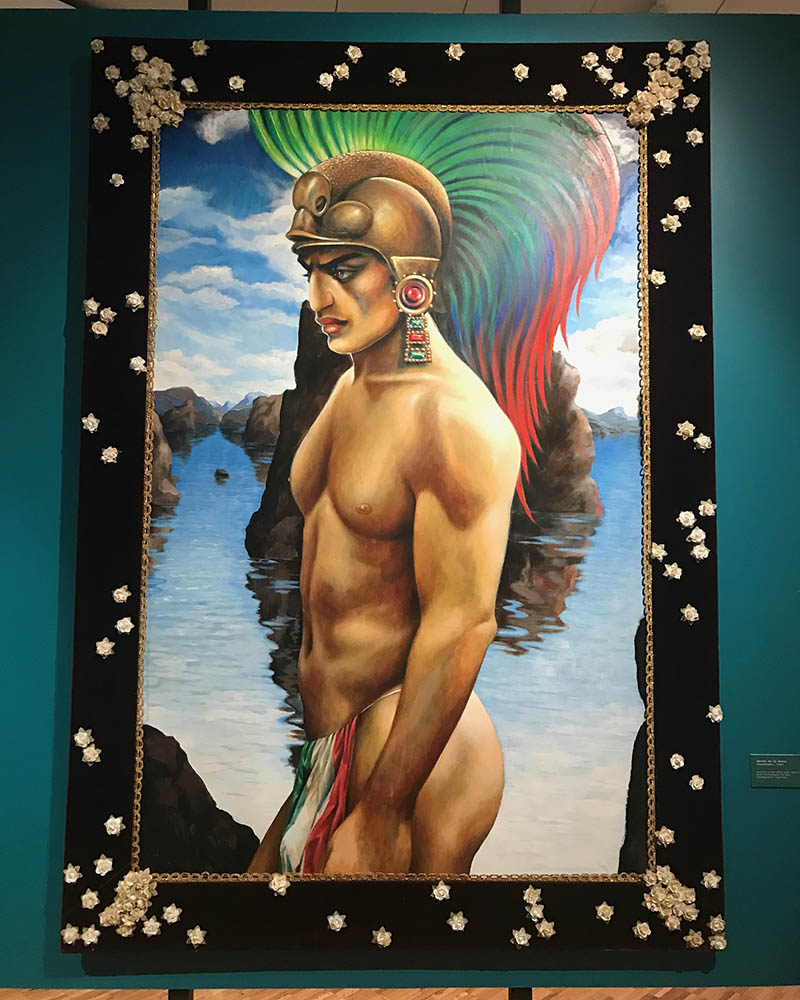

I also questioned the frequent, queer appropriation of tropes of Mexican nationalism. Mexico’s dictatorship had used these very tropes as propaganda, in order to foster a fundamentalist sense of ancient roots. It is too tempting for repressive societies to pink-wash themselves as progressive by leveraging an exoticizing Western taste for brown machos as LGBTQ+ representation. But as I left the museum, I wondered if I weren’t missing the point.

After leaving the museo, I met up with Mar Coyol, who is one of my favorite artists. I have greatly admired Coyol’s work, since seeing one of their paintings in a group show last year. And, when I began to follow Coyol on Instagram, I also found their selfies to be very attractive. Coyol had posted an announcement that they were selling prints of their work, and I bought one, hoping to meet Coyol personally.

As Coyol handed off their print to me, we spoke only for a few minutes before Coyol had to run. I felt disappointed, wanted to chat more. Wanted to learn more about Coyol’s practice as an artist. Wanted to visit Coyol’s studio, ask them out on a date. Instead, my desires took a queer trajectory: I returned to the exhibition, specifically in order to commune with Coyol’s painting, “Uniforme.”

Describing their painting, Coyol writes that the work expresses voices that “your LBGT and queer theory would not be able to understand.” As Coyol puts it, “your color is only white and ours, in addition to red and brown, is landscape” (my translation).

As I looked again upon Coyol’s painting, I realized that I had mistaken the painting as portraiture. But as Coyol points out, the painting is landscape. The revelation touched me deeply, where I felt myself still a frail boy growing up in the mountains of Appalachia, refusing to become a man but wanting to pick daisies, climb birches, and make friends with the partners or alter egos of “Uniforme.”

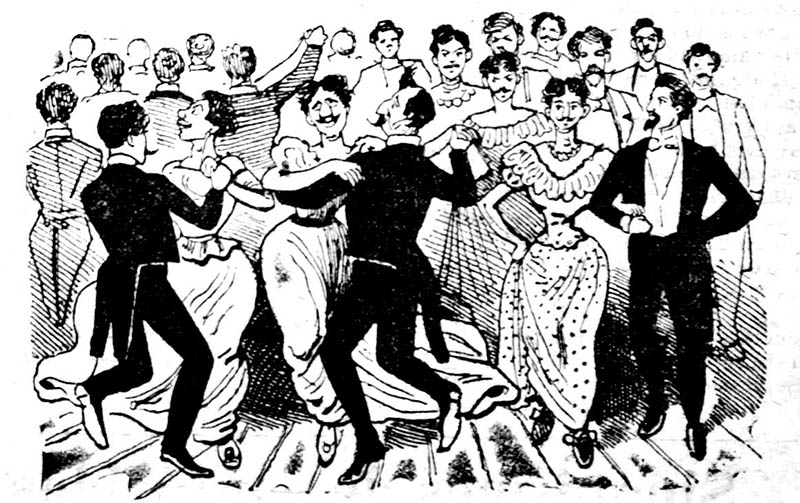

Passing again through the exhibit again, with Coyol’s insight, I looked not for figures but for landscapes. The background of Mexican queerness—according to elite historians—is the infamous Baile de los cuarenta y uno (“The Ball of the Forty-One”). In 1901 in Mexico City, police illegally raided a private home. Cops arrested aristocrats, dancing in drag. Some partiers escaped by paying bribes. Others suffered miserable prison sentences. As with the trial of Oscar Wilde, the scandal became one of the first times that the Mexican press openly discussed homosexuality. Imaginciones takes the Baile as a point of departure. News-clippings display José Guadalupe Posada’s nasty caricatures of upper-class homosexuals.

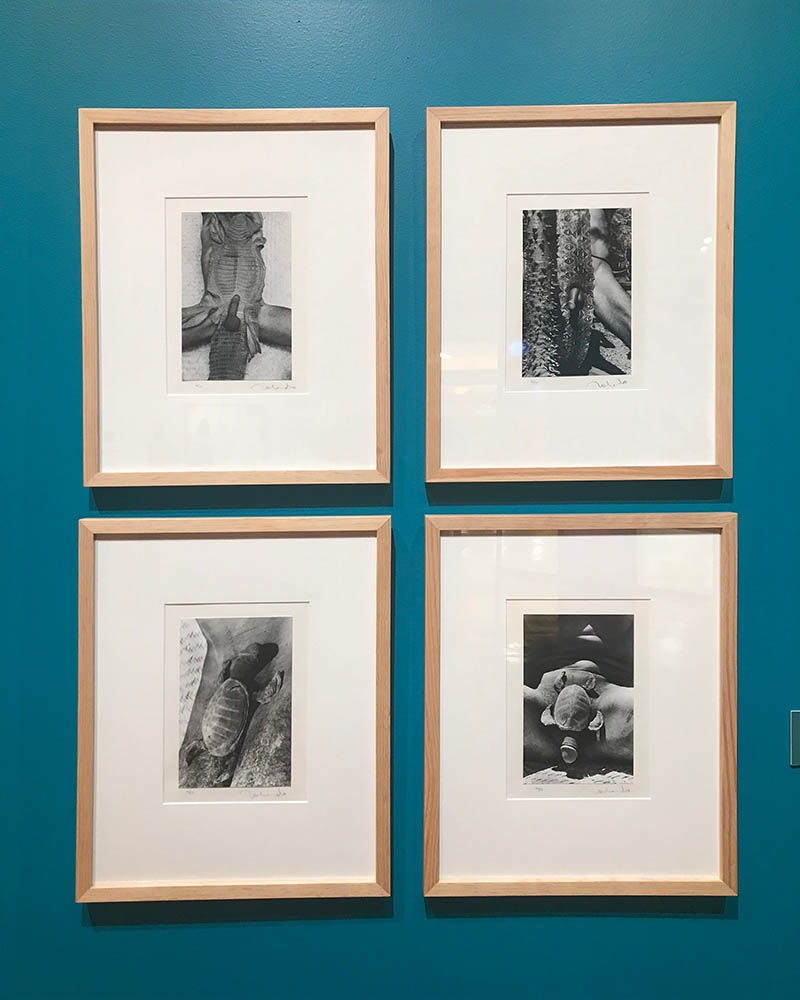

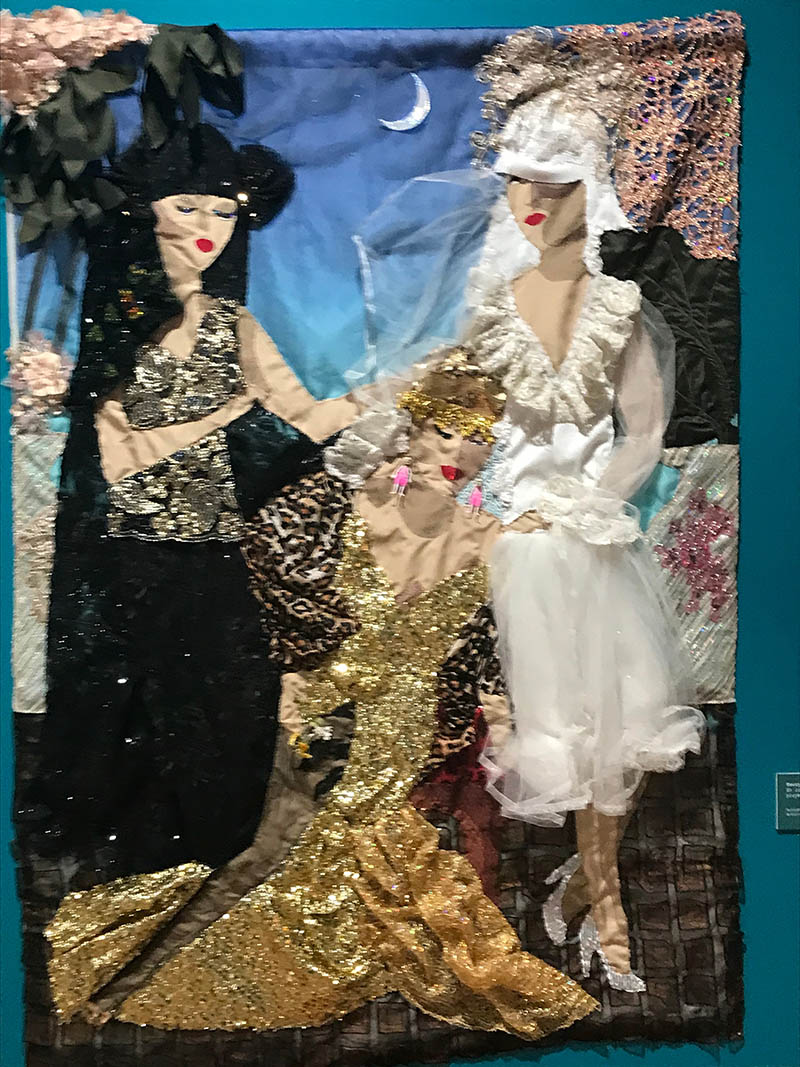

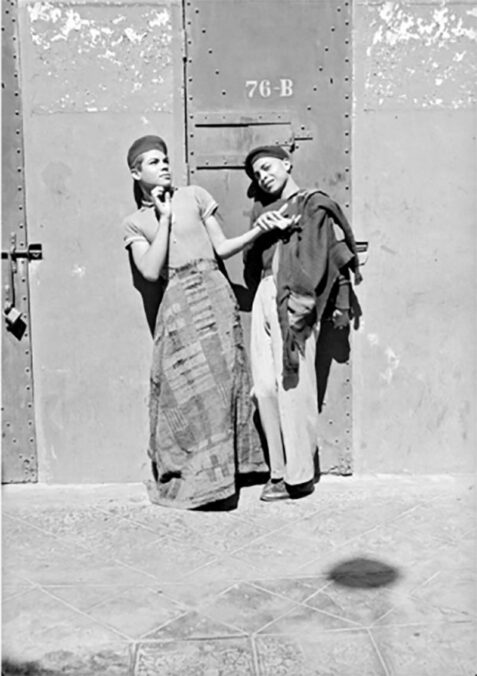

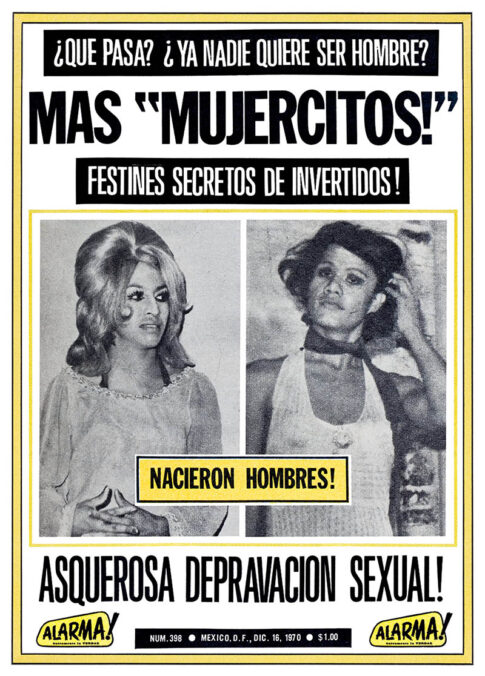

Yet the exhibition also complicates the official story that LGBTQ+ history started with aristocratic gay men. Juxtaposed with these images of the Baile, Susana Vargas appropriates mid-century news articles that salaciously reported on the arrest of working-class transwomen. Assorted photos from the 1890s through the 1940s show proletarian and indigenous queer peoples surviving and thriving during incarceration.

Estudio Casasola, „Homosexuales presos afuera de su celda,“ ca. 1925

Susana Vargas, Mujercitos, Editorial RM, 2014, print

These images tell a history that has been obscured by the legend of the Ball, a history of how queerness in Mexico has never been the sole prerogative of elites and elite institutions, but is also the history of the clases populares, glorying in the queer art- making of everyday life against a treacherous landscape.

The Western model for the modern nation-state—as well as the modern order of sex and gender—has been cruelly imposed on the queer peoples of Mexico. But the works of Imaginaciones radicales passionately resist—with art that expresses a queer desire to love and to fight, together, in a landscape that is brutal but beautiful, carrying roses, carrying machetes.

Exhibition: Imaginaciones radicals

Exhibition duration: March 18-October 22, 2023.

Address and contact:

Museo de Arte Moderno

Av. P.o de la Reforma,

Bosque de Chapultepec, Ciudad de México

mam.inba.gob.mx

A.W. Strouse, Ph.D., is the author of Form and Foreskin: Medieval Narratives of Circumcision (Fordham University Press) and Gender Trouble Couplets (punctum). Strouse is currently writing a book about the LBGTQ+ history of Mexico City’s subway system. Website: www.awstrouse.com Instagram: @putotitlan