Without much forethought, I wrote: I visited your site and really like your work „Ho Trovato“ […]. I wouldn’t worry about the form of the conversation. It could be anything – a narrative in a few lines, conversations of several pages, a personal diary… It took a week, and Mondini sent me back a diary with four chapters. And then it took me seven months to publish it (I can’t find a clear rationale for that). Each section arrived at a different date and time. Where the contributions are written, we don’t know. What is known is that most of them were sent during a period of train commuting […] The email opened with a diary section written in Italian, which then was accompanied by a section in English. Now that I look back, this correspondence was born without intention in two languages.

Chapter I: Birth. I remember it was late winter. Not because I have a particular historical memory of the events of my life, but because this work was born at a precise moment in my school career. In that period I was enrolled in the first year of the Brera Academy of Art, in Milan, and I attended the painting course of Alberto Garutti, a great artist and a famous professor, who had left an indelible mark on an entire generation of Italian artists over the past 20 years. I had already broken the ice with him – or better say finally gotten to grips with him in which nothing was taught, and it was magnificent. That classroom was an open space, in which a student was considered an artist and who was asked to present a work of such level as to stand up to comparison with the Venice Biennale. The responsibility was very high and everything took place in an empty classroom, with the poor unfortunate who had to install his work in the white space and wait for the response of the maybe another word:) Needless to say, the tension was always sky high, not so much for Alberto, who despite being always very lucid, direct and raw, was a person of great humanity, but for the judgment of the other artists present, who had already passed under the clutches of that judging assembly and could not wait to be able to express all their ill-concealed impatience about you. This work was born from there, from that context. From that world that was an inexhaustible source of oxygen for someone like me who came from a sleepy and static provincial town, hungry for new horizons.

Just one sentence: „This work does not work, but you will do a day some good works.

So clean and shiny, but at the same time warm, had been the tombstone that Alberto had placed on my work previously shown in the classroom. The arguments born in that context centered on the fact that, in my work, I was still too tied to the „belly“ of things, while my conceptual part was still immature. My work suffered from this, yet I have always been good at thinking, analyzing, arguing and studying. But then why couldn’t I? Why was I still so fragile? In the class I was one of those who stood out when it was necessary to destroy the work of another and I never gave up until the discussion highlighted the sides I considered fundamental. Where did all that sagacity disappear in my work? It was that question that made me understand the great gesture of generosity I was witnessing, day after day, lesson after lesson. Alberto used his experience not to humiliate you (in my opinion we were very good at doing it alone) but to convey a vision, a perspective on yourself and your work, improving not through tricks or shortcuts, but by using your emotional growth. „You can be a despicable person, I don’t care, but in your work you can’t lie“ Already that’s what was missing: the Truth. A job that was truly felt, truly the fruit of a necessity, which belonged to you but at the same time belonged to anyone. An act. Returning home I understood that that work had to start from the head, from a thought that in turn had to generate an emotional thrust aimed at crystallizing everything in a work. Free emotions were small. You had to go deep and not scratch the surface of things. Those that followed were weeks of inactivity … I was constantly thinking about what I really meant with my work. I did not produce anything, but I just reflected, never settling for the solutions I found, always partial and inaccurate. It was frustrating for me not to find that truth I was looking for. I had too many questions that I had been dragging along for years, meanwhile I was reading 1984 at the time. I don’t know if this also affected my vision, but I was sure I had to find a small solution to a small problem if I wanted to start building a ladder that would allow me to get out of that black hole of conjecture I was creating.

Then I realized … I found more truths in my false solutions, in my lies, rather than lies in my truths.

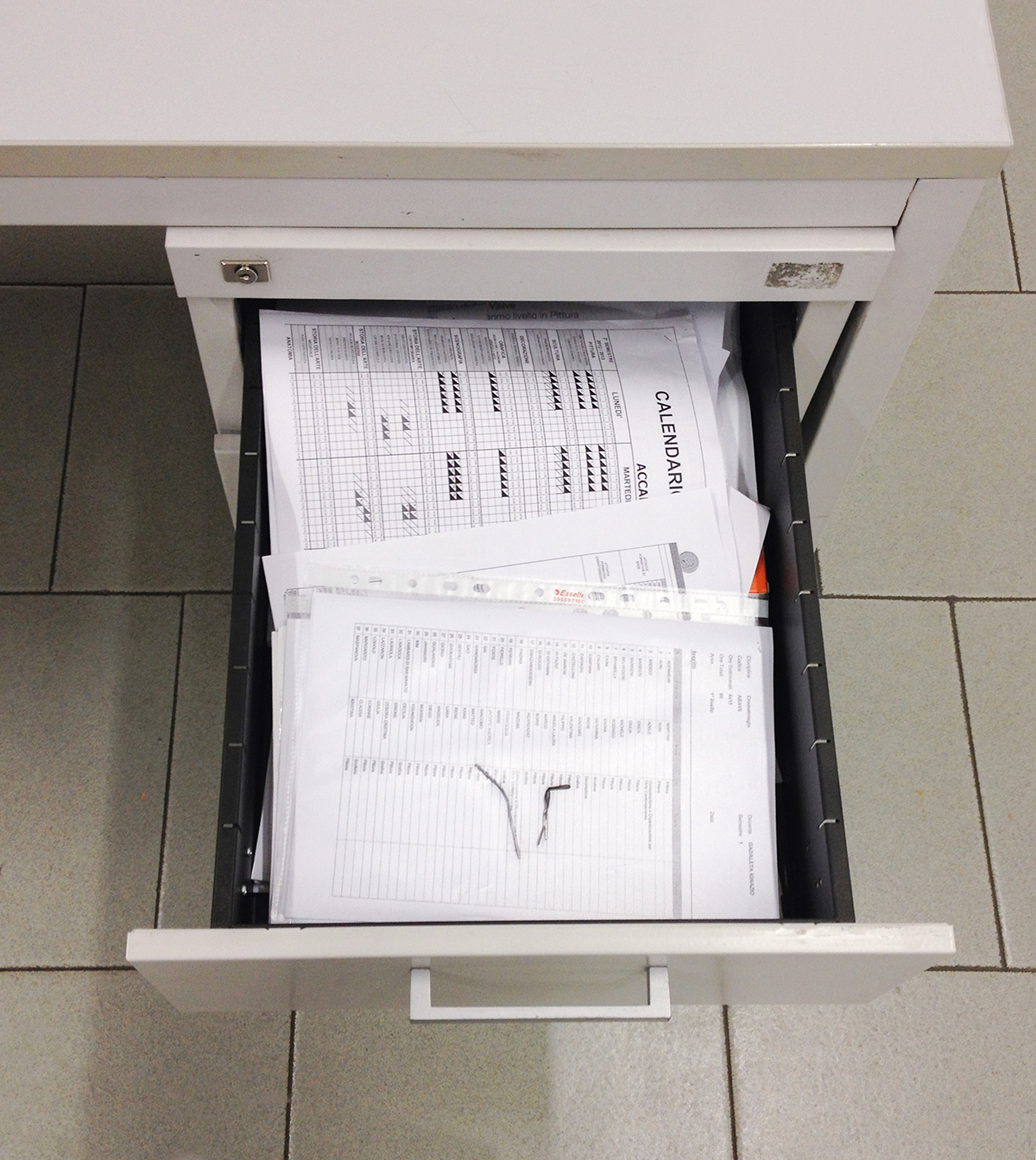

Chapter II: Presentation. Here we go again … Anxiety, the adrenaline rising, the feeling of having done a shit … the desire to run away and not present the work. In short, the usual start to the day that precedes the opening of an exhibition or the presentation of a project. At least this was what I felt then: a mixture of anguish and euphoria shaken together. As always, I arrived very early in the Academy. At the time I was still living in Parma and had to undertake a journey of almost 3 hours to reach Milan to attend courses. Inevitably, I always arrived before the others, not because of my excess of punctuality, but because of a lack of trains on that route, which forced me to leave at dawn to arrive in time for the morning lessons. Advance gave me plenty of time to complete my plan. Obviously I had done some tests at home … I had first tinkered with an old padlock found in a drawer and then with the lock of a small red safe, similar to those used in fairs to keep money. The results had been encouraging. I had also built the tools of the trade … Two small pieces of wire, bent as needed to leverage and align the teeth of the lock, had served my purpose very well. In that day would have been a drawer of the classroom 1 chair … and perhaps the thousands of questions that still floated in my head and inexorably tried to find an answer. I did not know if my little domestic preparation would come to help me in the decisive moment or if that lock would prove to be unblockable, at least for me. Entering the room I immediately went to my goal. I turned on the light and started tinkering with the iron wires.The lock didn’t move … Not bad, I was alone and nobody knew that my experiment was failing, so I didn’t give up and kept trying, I didn’t want to fail. I didn’t want to put myself in a position to feel once again not up to par. With these thoughts that were whirling in my brain, I finally opened (I still don’t know how) the lock, which made a strange noise and literally slipped out of the cylinder that contained it … I had opened the drawer but perhaps I had broken the mechanism. Today I think if this detail is really important, but at the time it was a fact that struck me a lot and my reaction struck me even more.

I didn’t think about it. I was too deep in my thoughts to wonder if that could be a problem. I had to start the installation and think about the work. I was going to deal with all of this later, so I started pushing the desk towards the center of the room, moving it from its normal position next to the entrance and giving it a leading role. I opened the drawer, placed my burglary tools on top of a pile of documents and sheets with class schedules, symbols of my success, and took some pictures to fix the scene. There was still half an hour left for the beginning of the lesson … and I was alone. A regulation imposed by Alberto was required to present the works in his classroom: First, they always had to be already prepared upon his arrival. Second, the space had to be perfect and free of any distraction or object left there by chance. Terz, you had to accompany your creation with a text written by you that had to summarize the thought of the work.

I still have that text, printed on a4 sheets.

In short, everything was there. Everything I could control, except the reaction of the „public“ to my action. Little by little the first colleagues began to arrive …. someone looked alarmed and questioning, seeing the desk in the center of the room and nothing on the wall behind. Others sneered mockingly as they took their seats, already enjoying the scene that would soon begin. Last, as always, Alberto arrived. He did not get upset in the slightest in not finding his desk in the usual place and immediately walked briskly towards the center of the room, where I was waiting for everything to begin. He did not even greet me, took the paper that I handed him and with his glacial gaze (he always spoke with his eyes even when he did not want to. I have never seen eyes like that again) and began to read aloud standing up, next to me. As soon as he finished he glanced into the drawer, went with his usual brisk step to a corner, retrieved a stool and with it in his hand he went back to the center of the room and sat down. A question: „What does this say to me?“ I replied: „Nothing, but it was useful for me to understand something that I still didn’t know I could do.“ There were moments of silence, some buzz and some giggles. Then a third year boy intervened, one of those „good“ and arrogant at the same time, who already felt ready for the great galleries and museums:“So what do we care about seeing a work that is a conversation between you and you? What do I see? Nothing. What do you tell me? Nothing. This work does not exist. “ He asked me a question and gave himself the answer. Alberto nodded. Other people also intervened, all very doubting about my work and not at all „parsimonious“ of negative comments. The mistake of revealing too much of the mystery that often surrounded the works exhibited in that room. That clever and devious unwritten rule that aimed to turn speech into a smokescreen rather than a revelation. I have always been very naive in this. I wanted to understand, not to be duped by beautiful words. Of those I found as many as I wanted in books or in some articles in art magazines, but Alberto’s presence made me more and more frustrated. He was standing next to me and didn’t say a word, then he intervened, taking the floor. With two sentences he verbally destroyed what little was left of the work and said to me: „This was a test for you, not for us. But from here you can do nothing but go up. It is not a good job, but it is a necessary job. .. even if this is still not enough for us, the art public.“ At that moment I understood that it was all true. I was so immersed in thought, in my need, that I had taken it for granted that the solution to one of my problems, albeit fictitious, was of some interest also to the others present. I became aware of the fact that problems are something to be faced in solitude and that art must be an open result of that path, not a solution, but an activator. This is still true for me today, but the show had to go on. 5 minutes to put the chair back in his place and move on to another boy’s work. From that day on I began to question the thought, to no longer believe in finding solutions by reflecting. It can be said that I completely killed the thought of the work that day and for a long time, almost a year, I wandered looking for something equally concrete with which to fill that void. I was looking for another way to reach something that was not yet in focus, but that was necessary.

That work was never appreciated. It is indeed my least known and least addressed work. But it was a watershed for me.

Chapter III: Elaboration. Almost 10 years have passed since that work. I was very young, now younger. I was constantly looking for approval, of myself and my work, but above all the thing that I miss most of those years was that absolute conviction of being in the place created the avant-garde. Where I finally found people who spoke my language and lived off my emotions. That strange feeling of being in the right place, at the right time and just having to work. The rest came by itself. Here, that work presented in that winter of 2013 was the beginning of my real growth. I dismissed the boy’s dreaming eyes and began to doubt that the world could actually be synthesized and grasped in the entirety of him. In other words I realized that I am not omnipotent, as boys often feel when they take off for the first time. I am more aware now, but perhaps even more daring. A series of other projects followed that work, which they did not do other than to ignite in me the desire to find something that was self-sufficient to exist in the art world … Extremely risky projects and at the same time absolutely cryptic and closed, almost as if the lack of that conceptual backbone made the walls of the ‚work, closing in on itself with very few glimmers of light to be able to access it. It was a spasmodic search, certainly exhilarating, but at the same time something had inevitably broken. At the time, I still didn’t realize that what I was about to take was a necessary step. I limited myself to concentrating on the contingent problem, not seeing the situation as a whole. I went to live in Milan, I started working as an artistic consultant and as a waiter to support myself and I attended the usual inaugurations and conferences that blossomed and shrunk in that city of just one week. It was hectic, but not inspiring. Many things, but little quality.

An overdose of images, moments, sensations, but nothing that remained in you longer than the spritz in your glass. A Milan of contemporary art to drink, but which then gave you the effects of a hangover without euphoria.

My problem was not being able to understand anymore if my art belonged to me … there were too many things that were happening outside of me. Too many ideas but no real stimulus. Too many things that weighed you down. Too much work in a city that is almost a metropolis and, as such, sucks energy even when you just walk down the street, so I decided to give myself a limit. As always, I had questioned myself as a person and all that living in the art world had created a sort of detachment from myself. I wanted to understand if making works of art was a necessity for me and not just a simple exercise in style influenced by the proximity of people who lived and moved in that context. I had lost the challenge with myself and my works were suffering from that lack. They were mine but at the same time they were made thinking of a me outside of myself, so I decided not to do works for 2 years, and I felt terrible. I threw headlong into my work as an Art Advisor so as not to think about the thousand flashes that crowded my mind. I started collaborating with galleries, artists and museums to carry out their projects. Mine, on the other hand, were secretly locked in a drawer. Every time a job was to be done, my head got into motion and my desire to take matters into my own hands came out, but I forced myself not to „do“. I had to figure out if mine was a conditioned reflex or a necessity. Yet the head always went there, always to carry out works, always to materialize that glow that every now and then I caught in an event, a person, a situation. Always ready to crystallize that emotion by depriving it of its heaviness and giving it its stage simply because it existed. The only thing I liked to do was also the one that hurt me the most. But I had to understand. They passed very slowly, and my rebirth was even slower. But I understood that for me, art is a necessity, not a tinsel. I am no longer that omnipotent young man of 10 years ago, I simply do not have any more that need.

Chapter IV: Left on me today. Sometimes I still feel that strange energy that made me believe I can enclose the whole world in a single work of art. That idea of having a granite and essential certainty in your hands. Some traces of it have remained in my work today: surely the sleepless, restless nights, searching in my thoughts to give shape to something I feel but still eludes me. Having abandoned the idea that the concept of the work can act as the identity of a work. Eliminate any conceptualism and any sense to find, whether it be a painting, a performance or a video, even if, in the end, everything ends up having one. But I see art more and more as a language, a form of communication and how it communicates. Poets are given words, artists are given images … We have to use those, without loopholes. Attention to the form that must itself be the message, the activator of a sensory awareness made up of small discards, contrasts and suggestions, which do not have the purpose of giving answers, but of activating emotional intelligence. Trying to deprive the work of a common sense, explanation or any imagined form. There is not much left to cling to in order to try to justify what you see, causing us to no longer think of Art as a definitive form. Works only to be experienced, free not to find a place in our reference points. Today for me there are only digital forms. A possible beginning that leaves the rest to each of us. Like an activator, which awakens from numbness, circulates the blood in the veins but reveals nothing to us, they trigger the emotions and consequently the thought, but they do not direct it. Pushing oneself to the position of thinking that art is not culture, does not have in itself any educational possibility or the transmission of knowledge. It is simply an emanation, Chapter IV: Left on me today a mirror or a product of us, unable to express anything else to the outside of itself. It is like the sunset or some cloudy skies that I see in Tuscany. They have no sense, no transmission of knowing. Yet, they excite like the things most dear to us. They belong to us and speak to us, filling a space that never shrinks. Art tells us nothing that in reality we do not know, but sometimes it shows us something already present in us in such a clear and lucid way that it appears to us as a revelation. We think of any work, of the present or of the past, we find ourselves inside Love, Death, Suffering, Ecstasy, Beauty, Horror, we already know them, we see them every day. But seeing doesn’t mean understanding and sometimes what we don’t understand doesn’t mean it’s necessarily wrong. Is this the case for all art? I do not know. I just try to do it with mine. Sometimes we find truths, even when we weren’t looking for them.

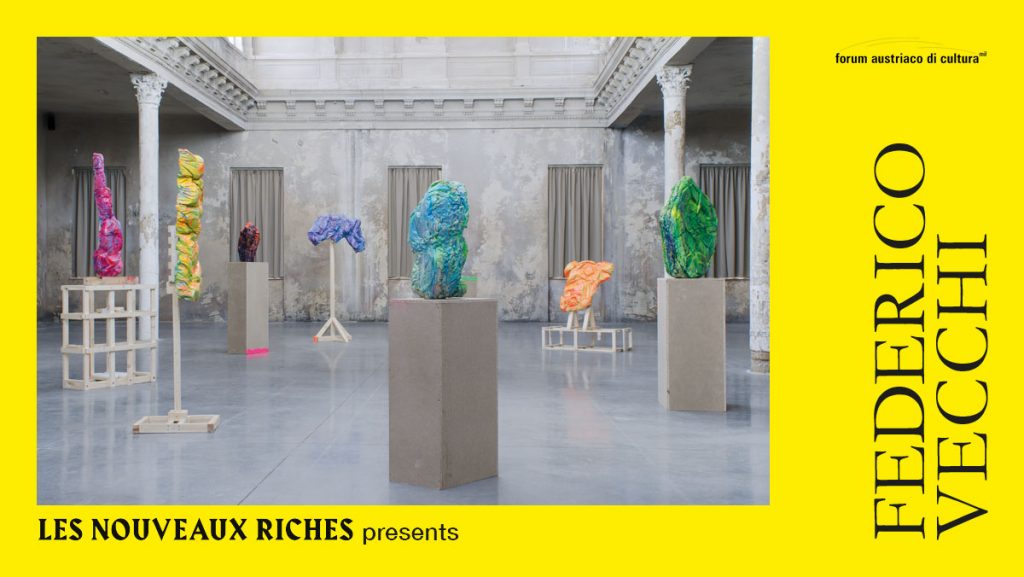

Max Mondini (Parma 1990). Trained at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts (Milan) and the Florence Academy, his work is divided between artistic activity and the profession of Art Advisor. He exhibits galleries, independent spaces, museums and art residence including: Palazzo della Triennale (Milan, 2012), Museo del Novecento (Milan, 2013), Villa Croce Museum (Genoa, 2015), Luigi Pecci Museum Center for Contemporary Art (Prato, 2020), Manifattura Tabacchi (Florence 2020/2021), Eduardo Secci Gallery (Florence, 2021) and Monza Biennial (Monza, 2021). As explained by the artist, his works “are to be experienced, free not to find a place in our cultural reference points. The purpose is to activate the emotionality and consequently the thought, but not to direct it. They impose a new perception through the forms, setting reactions in motion in the viewer and leaving the rest to each of us – https://maxmondini.weebly.com/bio.html http://www.instagram.com/maxmondiniartist

Erka Shalari (*1988, Tirana) is a Vienna-based art author. She focuses on discovering independent emerging artists, unconventional exhibition spaces, and galleries that have deliberately broken new ground in their working methods. In this regard, she relies on unorthodox publishing practices, coupling these with a nonchalant manner of writing. The work oscillates between articles for magazines, exhibition texts and press releases – http://linktr.ee/erkashalari