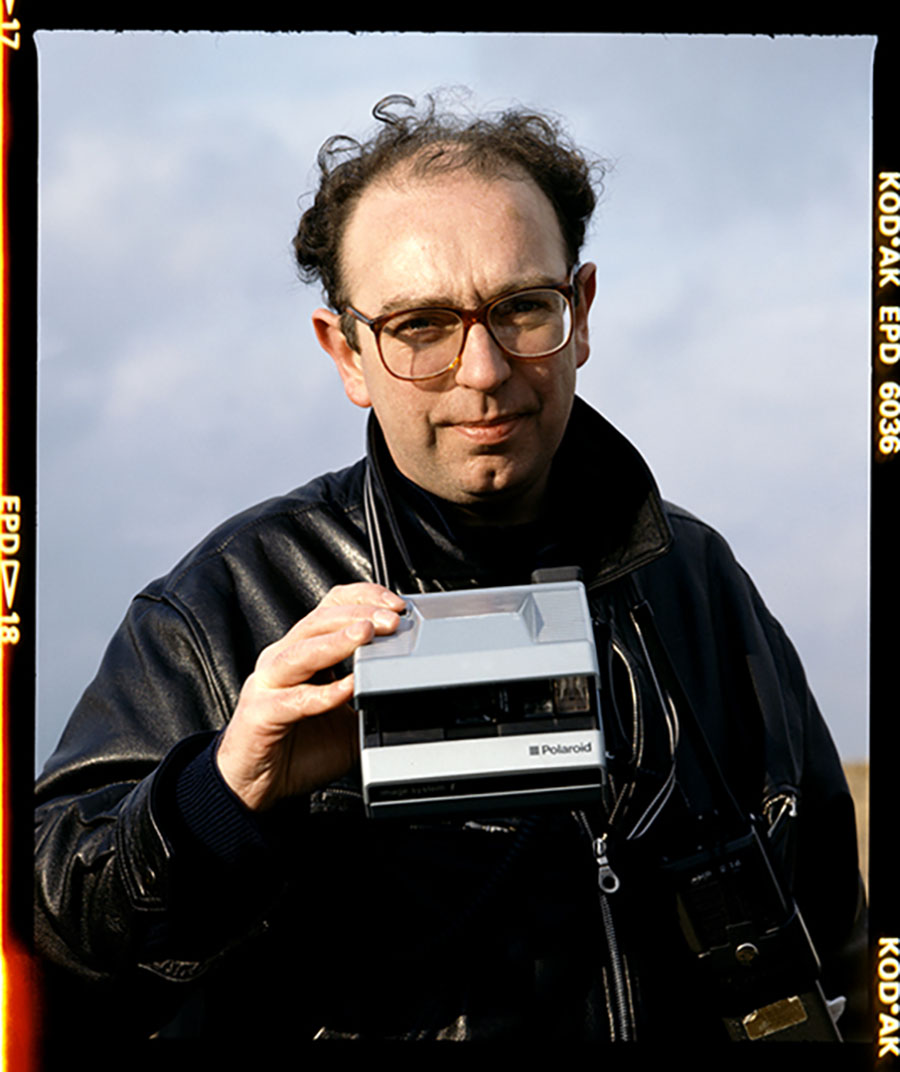

With a history of frequent visits and creative collaborations in the city, Mackay shares his experiences of bringing Jarman’s work to Vienna, including the poignant film Blue. He also delves into the unique filmmaking process with Jarman and his transition back to curating, preserving Jarman’s legacy for future generations.

How does it feel to be back in Vienna, especially to discuss the legacy of your friend Derek Jarman?

It’s very exciting to be here. I like Vienna a lot, —I’ve visited often, collaborated with Viennese artists, and attended various film screenings and openings. In 2008, we brought Derek’s work to the Kunsthalle Vienna with the exhibition Derek Jarman: Brutal Beauty, which included his remarkable monochrome film Blue, made just a year before he passed away. That film is a deeply moving portrait of Derek as he was losing his sight, and it’s always meaningful to share his work with new audiences. So being here for the FRAME[O]UT Festival at Museum Quartier feels great, and I hope I’ve provided the audience with some closer insights into Derek’s work.

At the FRAME[O]UT Open Air Cinema, we watched The Garden from the year 1990. Can you share how you first met Derek and perhaps any memorable anecdotes from that time?

I first met Derek in the late 1970s when I was running a cinema and filmmaking school. I had seen some of his Super 8 films in London galleries and was intrigued by his work. In 1979, I invited him to do a screening of his Super 8 films, and that’s how we officially met. We’d crossed paths socially before, but this was the first time we connected. Our collaboration grew from there—I was programming for the Edinburgh Film Festival and the Berlin Film Festival’s Forum section, and Derek and I started working together on preserving his Super 8 films. The Super 8 is a very fragile format, because of it is used- the same film that was in a camera for filming is the one to put in a projector for screening, so we raised funds to make copies, but soon we moved on to creating new films together.

![FRAME[O]UT open-air film cinema](https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/wp-content/uploads/james-mackay-11-845x676.jpg)

![FRAME[O]UT open-air film cinema](https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/wp-content/uploads/james-mackay-13-845x676.jpg)

![FRAME[O]UT open-air film cinema](https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/wp-content/uploads/james-mackay-12.jpg)

Derek’s filmmaking process was far from conventional. What was it like to prepare and shoot a film with him?

Derek’s approach was unique. For The Last of England, for example, we began by filming scenes with various people, experimenting with ideas and images. The film was meant to capture a portrait of England in 1986. Derek’s films were often constructed as a series of sequences—sometimes meticulously planned, other times more spontaneous. We would work out the shooting schedule as we went along, involving friends who were as passionate about the project as we were. We were also making music videos at the time, and the money from those projects helped fund our films, allowing us complete creative control. By the end of The Last of England, we edited a rough cut and showed it to Channel 4 and British Screen, who provided additional funding to complete it. The film was well-received at festivals in Berlin and Tokyo. When Derek inherited some money from his father, he bought a place in Dungeness, and we decided to film there. Dungeness had this otherworldly quality that was perfect for The Garden. We filmed over nine months, capturing landscapes and scenes. It was a very organic process, and we managed to secure funding from the same people who helped with The Last of England.

After your time working on films, you returned to curating and gallery work. How did that transition come about?

Curating was something I had been doing even before I started working with Derek, so it was a natural return. Producing films, especially in the way we did, was incredibly rewarding but also very challenging. Eventually, I found myself drawn back to curating, which is where I feel most at home now. I work with the Luma Foundation, overseeing Derek’s Super 8 films and other works he produced. From 2001 onwards, I ran a moving image event in Cambridge called Microcinema, showcasing artist films twice a year. It’s fulfilling to be able to preserve and present these works to new audiences, ensuring Derek’s legacy continues to inspire.

FRAME[O]UT – www.frameout.at, www.instagram.com/frameout_festival

James Mackay played a key role in shaping the British avant-garde cinema scene. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, he played a crucial role as the London Filmmakers‘ Coop program director and curated film programs at prestigious festivals such as the Edinburgh International Film Festival and the Berlinale. Mackay’s collaborations with Derek Jarman in the 1980s and early 1990s resulted in iconic films such as Imagining October, Angelic Conversation, The Last of England, The Garden, and Blue. He has also produced films by Ron Peck, John Maybury, and Nina Danino and music videos for well-known artists such as The Smiths, Bob Geldof, and the Pet Shop Boys. Since 2000, Mackay has focused on curating moving image works for galleries and festivals, including the Microcinema series at the Cambridge Film Festival. He is a member of the Prospect Cottage Residencies Panel and an advisor to the Luma Foundation.

FRAME[O]UT open-air film cinema took place every Friday and Saturday from July 12th to August 31st in the MuseumsQuartier, Vienna, AT. FRAME[O]UT is as every year since 2020, done in collaboration with Museum Quartier. The motto of the festival this year is „GARDEN“. Gardens are not just physical places; they reflect identities, dreams, and visions. They are deeply rooted in culture and demonstrate our connection to nature. In times of climate crisis, threatened biodiversity, and social injustice, FRAMOUT 2024 transforms the GARDEN into a venue for change. Familiar garden metaphors are reinterpreted through cinematic perspectives. The film program, spanning 16 evenings at the open-air cinema in MuseumsQuartier Vienna, presents narratives of a barren garden becoming essential for survival at the world’s end, social and biological microcosms in urban spaces, virtual gardens, underwater gardens, holiday destinations as „Garden of Eden,“ and more. Cinematic fictions depict the garden as a place of growth, blossoming, and withering. In short film programs, we encounter talking plants, giant asparagus, and secret gardens expressing fantasies and desires.