They like to chat and to offer advice, they are disposed to tell tall tales. They either obscure or reveal. They are nomads for whom the journey itself is always more important than the destination; actresses who, like the cat in the box, exist in all possible states at the same time; or voyeurs who influence the events through the very act of observation. The events we speak of take place in Poland, in a white and homogeneous land, where, according to Mickiewicz, a well-known cloud-buster, the clouds resemble grazing sheep or, as poet Jasnorzewska would have it, they seem like ruthless rolling boulders. In Poland – Alfred Jarry would add – “that is to say: nowhere”. This cloudy island, swollen with lofty descriptions, is only one part of the scenography; it is an imaginary planet, a dreamed-up utopia. The scene in which clouds mimic smoke, the moon becomes a huge backside, and the nationalized idea of tolerance is yet another bogus construct. Here enters the Other – even if he does not come onto the stage – who does not pretend that something exists when it doesn’t, thus contradicting the predetermined rules of the game; a passenger on the Narcissus, collective traumas and fears swirling around him like in the eye of a storm. An idealist tired of vengeance; a resident of an oppressed country; Captain Nobody; King Ubu endlessly repeating “merdre”; Segismundo firmly convinced that all this is just a dream.

Jasmina Metwaly, Downfall, costume, 2019-2020 (Collaboration: Marta Szypulska)

Krzysztof Gil, The First People, oil on canvas, 2022

Cloudiness, exhibition view

Meeting the Other, writes Slavoj Zizek, is accompanied by the question: what it is that he wants? This question, in turn, fuels a fantasy, which – like a contourless stain – fills the void and masks the inconsistency of the symbolic order. It acts as an anxiety-sucking hole, a swirling piece of imagination that, by staging our desires, opens up reality. Or perhaps it is an anamorphic cloud that suspends the meanings of previously seen images, changing the meaning of things that are yet to happen. Emma Goldman notes that the minority is always on the move, going forward and carrying the banner of freedom, while the mass branded with its own weight remains static, permanently paralysed.

This exhibition is another minority report, a story about exclusion and discrimination, phantasms and mythologies, but also an account written from a Freudian dream navel, from a place where perverse desire collides with an unknown land and a fairy tale in which, like in Krasicki’s works, the earth complains about the clouds that obscure the sun, even though she knows that in fact she herself is conjuring them. In 1928, Bruno Jasieński writes “I Burn Paris” in response to “I Burn Moscow”. He sets fire to the synthesis of social, national, and racial conflicts and he watches as it slowly fills reality with smoke. In other words, “Cloudiness” is phantasmic criticism, which, as Tomasz Kozak would have it, allows us “to feel and explore the fiery fire of history in such a way that it does not burn houses, but ignites the imagination”, and also, to enter the space of two rooms, now connected by a passage. The enfilade opens. While the former allows you to watch swirling smoke, the latter only voyeurically spies upon it.

Maja Ngom, The Sweet Taste of Otherness (Black Magic, The Magic of Double Nature), installation, 2020

from left: Jasmina Metwaly, Downfall, curtain, 2019-2020 (Collaboration: Marta Szypulska); Krzysztof Gil, Bengoro, oil on canvas, 2021

Lia Dostlieva, The Cynocephali of Donbas, object, 2017

Taras Gembik, My secret chamber, movie, 2019 (Collaboration: Luke Jascz)

The clouds are colliding with each other and the swarms are charging. It is muggy and stifling, but the storm isn’t coming. The weather forecast for Friday is clouds and no precipitation. Nature twists and pants, but as Witkacy writes in “Insatiability” – enough of these damned landscape moods. Enough of these romantic visions that crash like waves, of repressed fantasies, of forgotten resentments.

One of the etymologies of the word “zachmurzenie” (cloudiness) connects it with the old Polish word “murzyć”, meaning to darken, to blacken, or to dim. This in turn refers us to “mohr” and then to politically incorrect terms encoding blackness and dirt, such as “murzyn” (negro) and “mores”. In this sense, cloudiness encodes not only fantasies, but also the underlying symbolic violence, becoming yet another anamorphosis, an unspoken question about empathy. “If you get injured, it doesn’t hurt me,” one of the witnesses of the Holocaust interviewed by Claude Lanzmann says to the translator. In the film – constructed, among other things, from landscapes full of the grey skies of post-war Poland – this fragment was not included.

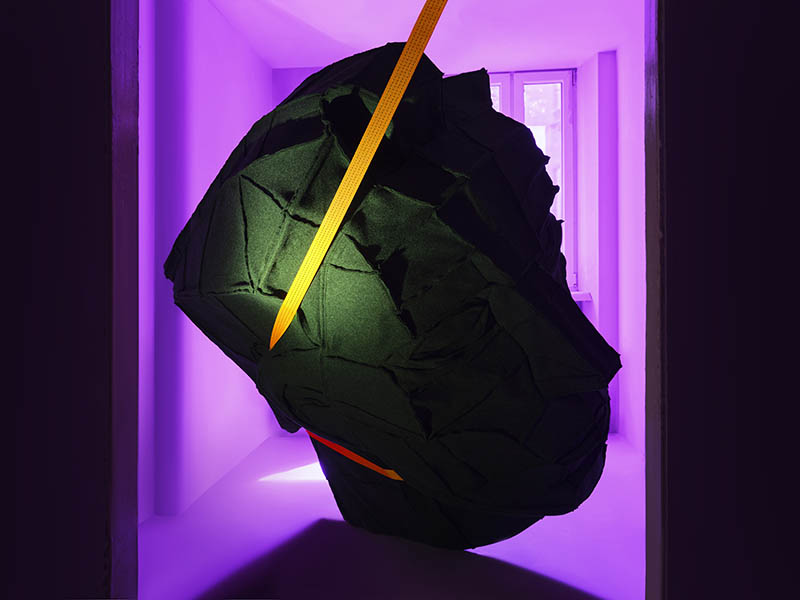

Ala Savashevich, The Unknown, steel and felt sculpture, 2021

Mikołaj Sobczak in cooperation with Taras Gembik, The Phantom, movie, 2022

Krzysztof Gil. In Romani, “czarować” (“to charm”, “to conjure”) also means “to give herb”. The installation resembles a wild and queer, exotic and paradisiac garden, a place that ostensibly belongs to nature, even if beneath the surface we sense the breath of power that organizes and suppresses expression. In the 1930s, but also later, the garden was written and talked about as a reflection of the social fabric, a vision of society in which there is no place for Others. Gil plays with this metaphor, evoking biblical motives, such as the tree of knowledge of good and evil, but also the figure of a snake – here with the face of the Polish aristocrat Izabela Czartoryska – and the dark or “merely” dirty Yahoos. European history, but also the iconography that encodes racism, violence, the hierarchy of masters and slaves, is intertwined here with Romani culture – of fortune telling, which not only influences but creates reality; with a Bengoro doll made of wax and hair, which the Roma threw at white people during fortune-telling, thus making it a demon of someone else’s fear; and also with the theory about the African origins of the first humans, an interspecies community, and the narrative of the excluded: people discriminated against or rejected on the basis of their race, origin, or gender. The garden shrouded in fog is a Chinese-boxes narrative about fantasies and desires; the forbidden fruit, which, marked with a symbolic otherness, tempts us until we sink our teeth into the fleshy matter. Only then does its imaginary power burst like an overblown balloon.

Mikołaj Sobczak in cooperation with Taras Gembik. According to Łukasz Kozak, the phantom is a flesh-and-blood man who has been excluded from the community of the excluded, and who either hides his phantom quality or plays with it. The movie tells the story of a ghost-exile deprived not only of a home but also of the right to vote, hiding in an Orthodox church that had been scheduled for demolition. It is here that he meets a Polish surveyor, whose presence ignites in him the need to vent all fears and unworked traumas. In this sense, the phantom is a medium that signifies and codes Polish-Ukrainian history, travels in time and talks with the dead, weaves a narrative related to Polish imperialism and colonial optics, the demolition and recovery of Orthodox churches under the pretext of their de-Russification, and the rebellion and uprisings of Ukrainian peasants whose anger was aimed at the authoritarian power of the Polish master. The Phantom allows us not so much to enter the church, which is not really here – the film was shot in the Warsaw Icon Museum, but to look inside a phantasmagoria covered in a sauce of nightmarish, onerous fantasy borrowed from German expressionism. It allows us to look inside the unconscious, the disclosure of which emancipates repressed narratives, journeys of discovered identity, looping violence. The latter is just as alive as the phantom in the title.

Lia Dostlieva. The myth about dog-people who inhabit the territory of today’s Ukraine has its origins in ancient times. Greek philosopher Simmias and the Roman historian Pliny wrote about the cynocephali: they supposedly lived in caves, communicated by barking, and did not have souls. With time, the artist says, the dog-headed people spread all over the world. Not only did they appear in books and paintings, but they also walked and continue to walk the same streets that we do. And yet, as the church fathers wrote in the Middle Ages, they are only half-human, and therefore they will knot know Salvation. In 2017, Dostlieva referred to the myth that became a tool of systemic exclusion, when the inhabitants of Donbas were deprived of their homes and forced to flee the territories occupied by the separatists. They were the cynocephali, seeking refuge among ordinary people, desperately trying to be like them. In the face of war, this new mythology of externally and internally displaced people has become the reality of all citizens of Ukraine. One of the most famous depictions of cynocephalus comes from the Kyiv Psalter, now kept in Saint Petersburg. The illuminated manuscript shows Jesus converting the dog-headed tribe. The codex was drawn up in Kyiv, but its subsequent owner, Abraham Ezofovich, a Jewish merchant, donated it to the Lithuanian church, and within its pages he wrote a curse that would fall upon anyone who took it away from Lithuania.

Ala Savashevich. “The heart of a statesman must be in his head,” Napoleon had famously said. I wish to chime in: and what if the head is in the clouds? Savashevich’s sculpture is a deconstruction of the political body, but it is also a symbolic revenge against the authoritarian power and its emblems. Marked by critical reflection, it is a nostalgic memory of toppled, headless statues, whose destruction paradoxically does not crush or weaken their power, although it may bring relief. The year is 1793. French Revolution is happening in the heart of Paris, and its inseparable part is the decapitation and destruction of statues and monuments – symbols of tyranny and fanaticism. Among others, the heads of all the saints of Notre Dame Cathedral had rolled. The year is 1979. In Nowa Huta, unknown perpetrators are trying to blow up the statue of Lenin under the cover of night. One foot gets damaged. The year is 2020. In Great Britain, during anti-racist protests, a statue of Edward Colston, a slave trader and philanthropist, is thrown into the river, soon after, in the United States, demonstrators decapitate the statue of Christopher Columbus. At that time, they also damage the statue of Tadeusz Kościuszko – the hero whose ethnicity has been pointlessly disputed between Poland and Belarus for years. The ghostly head from a non-existent monument is also the head of all statues and memorial that have been toppled in an act of social anger. It is both a trophy and the disposition of collective denial – but also a question: Who needs heroes and why?

Wilhelm Sasnal. The artist flies on board a Concorde in April 2003, several months before the final flight of this supersonic plane, which for many years had been an object of collective fascination, a symbol of luxury, technological progress, a fetish, and a commodified dream harnessed into the capitalist system. On the Kodachrome tape – incidentally, also obsolete today, but, not without significance, originally calibrated for the white skin tone – Sasnal is filming the view from the window: the blue of the sky, interspersed with the image of swirling clouds in its background. He then places the movie in a specially constructed projector, where eight rolls of tape, in a loop, move over the sandpaper that gradually wipes it until it is completely gone. The slow and initially unnoticeable atrophy of the amateur footage is not only connected with a supersonic utopia, but more than that: it seems to reflect the mechanisms governing memory, history, and the power of phantasmagoria. Work on supersonic transport began in the late 1950s. The Concorde, named after the Roman goddess of harmony and unity, was a joint project between Great Britain and France. Despite the astronomical budget, environmental costs, social and economic crises, the work continued, and the first Concord flight took place in March 1969. However, it was not the first plane to break the sound barrier. A few months earlier, the Soviet Union was winning the technological race. It is believed that the plans for Tu-144, commonly known as “Konkordskyi”, were based on materials stolen from French engineers. In retrospect, both projects would turn out to be a social and political failure.

Taras Gembik in collaboration with Luke Jascz (Łukasz Jasiukewicz). In the early 1960s, Vasyl Symonenko, together with his friends Alla Horek and Les Tanyuk, will find anonymous graves of victims – including those on the Ukrainian Katyn List – murdered during political repressions by the NKVD in the cemeteries in Bykivnia near Kyiv. He will report the case to the Soviet authorities, and a few months later, at the railway station in Smila, he will be beaten to death by the police. In 1965, when secret agents are trying to drown out the crowd at the premiere of Sergei Parajanov’s film, Vasyl Stus yells, “Who is against tyranny – let them stand up!” For participating in the first public protest against repression in the USSR, he is dismissed from the Kyiv Institute of Literature. A few years later, during the next wave of arrests, the court will sentence him to 5 years in a labour camp and 3 years of exile for “anti-Soviet agitation.” He will return in 1979, but less than a year after that he will be sentenced again, this time to 10 years in prison and 5 years of exile. He will die in the penitentiary after starting a hunger strike. In the mid-1960s, Lina Kostenko signs a protest letter against the arrests of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. During the trial of the Horyn brothers, she showers the defendants with flowers. She initiates protests to defend the writers, and pens applications for their release. She will find herself be on the blacklist of Soviet authorities. For dozen or so years, her work will remain unpublished. In his film, created as part of the “Silence Hotel” project, Taras Gembik collates the works of Ukrainian poets and poetesses, and fills the eponymous chamber with words that are the weapon in the fight against a totalitarian system – the system whose echo is still reflected on its walls. “Do you know that you’re human? / Do you know it or not? / Your smile – is unique / Your struggle – unique / Your eyes – are unique / Tomorrow you will not be here / Tomorrow on this earth / Other people shall walk / Other people will love / The good, the kind, and the evil” (V. Symonenko).

Maja Ngom. “I was in my teens when I recognized the rich, bittersweet aroma of cocoa that filled my life. I was a bar of chocolate. I was a moist chocolate cake with sour cherries. I was the chocolate jelly candy the kids got after Sunday mass. I was a deep red; the juiciest of strawberries – bursting with flames of sweetness. My pointed tits, decorated with raisins, sizzled on their tongues,” writes the Polish-Senegalese artist in an essay in which she talks about the paradoxical cognitive experience of her own duality, being herself, and being the Other – also from her own perspective. An installation consisting of a series of photographic self-portraits, and the curtain of hair – on the one hand abject, and on the other hand tame and familiar, because resembling kitchen beads – tells not merely the story of the “not entirely black and not entirely white” identity, but also of living in a homogeneous society, of symbolic violence, structural racism, stereotypes, stigmatization, and the language of exclusion – encoding substances such as asphalt, bamboo, or chocolate. It is a story about objectification, exoticisation, and subjugation of otherness, whose taste is so sweet that it is sickening. Especially when someone touches your hand, expecting to get dirty from your touch; when someone tells you to read “In Desert and Wilderness” as part of your school reading list; and while cultivating the tradition of Polish hospitality, someone treats you to a cocoa cake, which he calls a pejorative but by no means an obsolete name – a term to describe people with your skin tone.

Jasmina Metwaly in collaboration with Marta Szypulska. In its own way, each uniform is a costume – a disguise, the wearing of which can be read as a non-obvious performance, a manifestation of power, hierarchy, and social control. The costume created by the artist is a spectacle in itself – a bizarre hybrid, not devoid of irony, which grows into the body that is wearing it, while the curtain sewn from the leftover fabric not only reveals the existence of this here and that other scene, but also emancipates the need for identity mimicry – to become like everyone around you, and reveal the symbolic textuality which, according to Homi K. Bhabha, is the cornerstone of any survival strategy. Metwaly’s works are inspired by the story of a tailor working for the Egyptian armed forces who, by designing military clothes, contributes to the aesthetics of power, and at the same time makes an imaginary, quasi-theatrical and symbolically charged fiction a reality – the language of a larger community. In other words, Downfall is a deconstruction of political structures, an exercise of critical awareness, but also a mapping of common points, not only between Poland and Egypt, the past and the future, mainly in the experience of dispersion, in a tear that blurs the imposed norms and orders – social roles, genders, or identity. In the words of Lacan: “To imitate is no doubt to reproduce an image. But at bottom, it is, for the subject, to be inserted in a function whose exercise grasps it”. In this sense, mimicry is a stage of mirrors, behind which an imaginary anticipation takes place.

Exhibition: Cloudiness. Exhibition and accompanying events curated by Ania Batko, Aleksander Celusta

Artist: Krzysztof Gil, Maja Ngom, Lia Dostlieva, Ala Savashevich, Jasmina Metwaly, Taras Gembik, Mikołaj Sobczak, Wilhelm Sasnal

Exhibition duration: 25 June – 23 July 2022

Location: Sarego 25/16 Street, Krakow (Poland)

Special thanks to: Małgorzata Kołaczek, Joanna Talewicz, Sebastian Ciastoń, Jan Krawczyk, Paweł Gardynik, Joanna Sierant, Ana Bargiel, Bartek Buczek