I decide to speak with Sally Wright, the executive director at Catskill Art Space, to introduce his solo show „Forrest Myers“. On the occasion of the solo survey show, the director of Catskill Art Space (CAS) through August 26 discusses recent works and looks back at how his practice has evolved over the decades.

Can you introduce us to the artistic practice of Frosty Myers?

Forrest „Frosty“ Myers practice spans many artistic movements and genres, so much so that he’s likened his presentations to „group shows“. His practice has crossed many different artistic movements, including and not limited to light and space, minimalism, land art, conceptual art, and more. Frosty has gone so far as to acknowledge that had he stayed in one lane, he may have been awarded greater commercial success, but he’s remained steadfast in his artistic vision. I am continually taken by his pioneering spirit and conviction. So much so, he organized the first work of art to be placed on the surface of the moon, untitled [computer drawing] (1968–69), a small computer chip with drawings from himself and his peers Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, David Novros, John Chamberlain, and Claes Oldenburg to the furthest stretches of humankind. He and his work are truly out of this world.

Forrest Myers at Catskill Art Space. © Forrest Myers. Photo: Zach Hyman

Forrest Myers at Catskill Art Space. © Forrest Myers. Photo: Zach Hyman

In what way was „The Wall“ a product of its place and time?

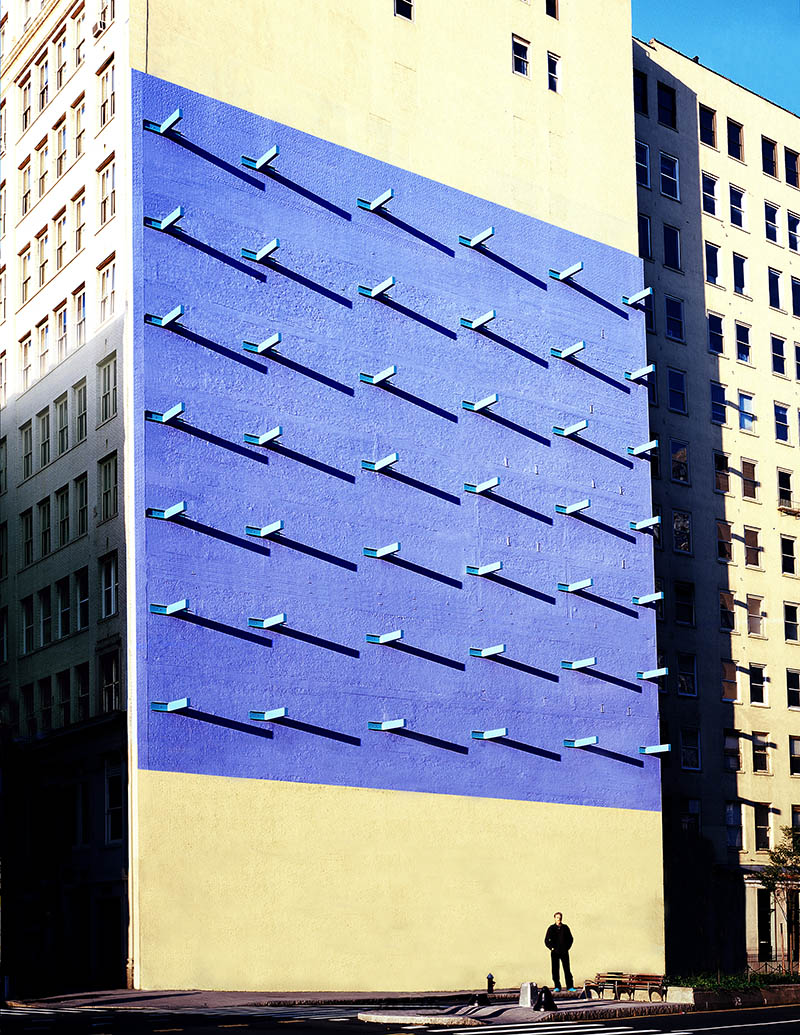

Under Robert Moses, former New York City urban planner, and public official, the city endeavored to expand Houston in SoHo to further automobile traffic, which was met with a mixed response as SoHo was home to many artists. With the expansion, an entire city block was destroyed, laying bare existing architectural joists that once supported an adjoining building. The building’s owner, Charles Tannenbaum, commissioned the work in 1973 for $2,000 to revitalize the exposed wall. Myers affixed 42 green-painted girders on a sea of blue background to the building on the Northwest corner of Broadway and Houston, and The Wall is often referred to as the „Gateway to SoHo.“

To this day, it is the largest public art in the city, and a landmark for artists, tourists, and residents alike.

How was the NYC art scene during this period?

The art scene in New York City was hugely dynamic and influential, and certainly not limited to the visual arts. There were tremendous synergies in art, music, and culture. These artists pioneered living and working in abandoned lofts and led the urban renewal in what became the downtown scene in lower Manhattan, Soho and ultimately Brooklyn. Affordable housing and studios allowed for and promoted the creation of new work. Frosty has acknowledged the New York City art scene at this time as a continuation of his art schooling. Specifically sitting Max’s Kansas City, a popular artist hangout, ripe for inspiration. There he spent time discussing conceptual ideas with his friends John Chamberlain, Neil Williams, Bob Grosvenor, David Novros, Mark di Suvero, Dean Fleming, Robert Rauschenberg, Walter De Maria, Jim Clark, Brice Marden, Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari and Mel Bochner. The earliest work in the exhibition is a laser-light installation, Woofer and Tweeter (Laser with Speaker and Mirror, 1963), which Myers conceived and realized at Max’s Kansas City. He positioned a laser in the window of his second-floor loft at 238 Park Avenue South, directed across the street to the front window of the bar and onto a small mirror affixed to the cone of a speaker that was attached to the jukebox. Pulsing to the beat of the music, the red beam of light was directed through the smokey bar to the very back of the club, over what was known as Andy Warhol’s table.

Forrest Myers at Catskill Art Space. © Forrest Myers. Photo: Zach Hyman

Forrest Myers at Catskill Art Space. © Forrest Myers. Photo: Zach Hyman

Can you introduce us to his solo show at CAS?

For CAS’s annual invitational exhibition, Forrest Myers’ survey spanned three interior gallery spaces and incorporates a new site-specific sculptural work on the exterior of CAS’s building on Main Street, Livingston Manor. A brightly colored T-shaped beam and segment of an aluminum channel mounted to the exterior facade of the building make an instant visual and conceptual connection to Myers’ well-known minimalist installation, The Wall. The majority of Myers’ sculptural work from the 1960s had minimalist geometric forms. By the end of the decade, his practice became more lyrical, and his geometric work flattened into two-dimensional reliefs. Two of Myers‘ largest early metal paintings constructed of oxidized and stainless-steel panels were on view, along with later versions powder-coated in bright colors. In 1969, Myers began making furniture, utilizing singular sheets of metal with reductive folds and bends to render benches, chairs, and tables from industrial materials. Myers explored other themes and motifs, shaping long segments of pipe, springs, and coils into maximalist beds, chairs, and tuffets. With compelling titles of works including Kilimanjaro (1990), Green-T (2007), I-beam Table and Chairs (2007), Manifold Chair (2018), Computer (1990), No Evil Bench (2007), Pink Chair (1993), and Love Bench (2007), the survey of Myers’ work at Catskill Art Space ignites the pleasure of the imagination.

I lived for a long time in LA, and I’m curious to know which differences and analogies there were between the New York scene and California in the 1960s.

I am especially taken by the similarities between the two scenes, considering Catskill Art Space’s long-term presentations from Sol LeWitt and James Turrell are shown in concert with Myers’ sweeping exhibition on the ground floor. East Coast artists were more closely concerned with hard-edge minimalism, while West Coast artists explored the pioneering use of the materiality of natural and artificial light. Working independently, the three artists share similar beginnings early in their careers. In 1965 and 1966, Myers and Sol LeWitt (New York-based), respectively, made large-scale sculptures based on the structure of an open modular cube (Myers – Lazers Maze, 1965, and LeWitt – Modular Cube, 1966). Large-scale sculptures by both artists were featured in the seminal exhibition Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum, New York in 1966. Working on opposite coasts of the U.S., Myers, and Turrell simultaneously pioneered the use of projected light as a sculptural medium in 1966 and 1967. Each artist debuted their light sculptures before a public audience in New York (Myers in January 1967) and in Los Angeles (Turrell in September 1967).

How has Frosty’s practice been in these decades?

Frosty’s work is hugely dynamic, and practice is ever-changing. In the last few years, he’s devoted much of his time to constructing a sprawling museum with over six decades of his work and a sculpture garden of his work in Damascus, PA, which features public access to the gardens. Together with his wife, Debbie Arch Myers, they’ve developed a stunning garden next to the Delaware River, which is accessible to the public from dusk to dawn. Unlike many other artists, he’s in the process of reacquiring much of his work that was out in the world and assembling a cohesive survey of his life’s work. He and Debbie are making plans to reposition the museum so that it is open and accessible to the public. This will be a tremendous asset for our local and wide art communities, and in this spirit, I feel the culmination of his life’s work to be his great magnum opus.

Address and Contact:

Catskill Art Space

48 Main St, Livingston Manor, New York 12758

www.catskillartspace.org

Camilla Boemio is an internationally published author, curator, and member of the AICA (International Arts Critics) and IKT (International) based in Rome. In 2013, Boemio was the co-associate curator of PORTABLE NATION: Disappearance as work in Progress – Approaches to Ecological Romanticism, the Maldives Pavilion at the 55th International art exhibition La Biennale di Venezia. In 2016, Boemio was the curator of Diminished Capacity, the first Nigerian Pavilion at 16th International art exhibition La Biennale di Venezia. Boemio’s recent curatorial projects include her role as co-associate curator at Pera + Flora + Fauna. The Story of Indigenousness and The Ownership of History, an official collateral event at the 59th International art exhibition La Biennale di Venezia, 2022 and she curated several exhibitions for Polo Museale Sapienza at Museo dell’Arte Classica and at MLAC Museo Laboratorio Arte Contemporanea, in Roma. Invitations to speak include the Tate Liverpool, MUSE Science Museum, and the Cambridge Festival 2021, at Crassh, in the UK.