You are in Vienna again in November, with a screening of your films on the 19th, followed by a conversation with Eva Sangiorgi, the director of Viennale, at Stadtkino im Künstlerhaus.

Yes, several of my films will be shown, including Fritz (2024), Head Falling 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (2015), Ludwig (2018), Monelle (2017), The Parents’ Room (2021), Untitled (All Pigs Must Die) (2015), and Dolle from last year.

![Diego Marcon The Parents' Room, 2021 [Still] Digital video transferred from 35mm film, CGI animation, color, sound 6 min 23 sec, looped Credit line: © Diego Marcon. Courtesy the Artist and Fondazione Donnaregina per le arti contemporanee, Naples. Supported by Italian Council (2019)](https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/wp-content/uploads/diego-marcon-video-still-03-883x676.jpg)

![Diego Marcon Ludwig, 2018 [Still] Video, CGI animation, color, sound 8 min 14 sec, looped Credit line: © Diego Marcon. Courtesy the Artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London](https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/wp-content/uploads/diego-marcon-video-still-02-889x676.jpg)

I would like to start with the writing part of your process. When writing the script for La Gola, are you writing pure fiction, or are there autobiographical elements as well? You write in Italian—how does the text change in translation, and does it lose something in the process?

There is nothing autobiographical in La Gola, and most of the time, my focus in writing isn’t on storytelling or dramaturgy. It’s much more about exploring language and its intricacies. The initial idea was of two lovers exchanging letters but not truly communicating—each is on their binary journey. The aim was to create a melodrama that unfolds on different levels: visually, with dramatic close-ups and crescendos in the music that unify these two viewpoints. On one side, Gianni writes about food, and on the other, Rossana speaks of caring for her mother’s health.

There’s an interesting anecdote: when I showed the film to my English-speaking gallerist, she watched it with subtitles, and I wondered how it would resonate with non-Italian speakers. She said it was sometimes difficult to grasp all the words, but that there wasn’t the need to follow everything or to get every single detail. The sense of the speaking was there. My process is rooted more in words and structure than in the story itself. La Gola doesn’t follow a traditional, linear story. Yet there’s something engaging, and I saw people staying until the end. It’s hard to pinpoint, but it’s seductive—the music, colors, and the sound of the voices.

„Seducing“ is a good word because, as a viewer, you’re drawn in just by entering the space: the red seats, floors, and the intimate setup of the big screen. It creates the anticipation of something dramatic happening, and the whole cinema installation transforms the Kunsthalle Wien room.

Yes, that’s true, and it could be seen that way at Kunsthalle Wien. But in another show at Kunstverein Hamburg, the setting was very different. There, we built a screen on an eight-meter-wide and five-meter-high wall in a large, empty space, the voices were reverberating so much in this huge space, creating a ghostly atmosphere. The screen allowed viewers to approach the characters‘ faces closely, a setup designed specifically for that venue. I always try to respond to the space in my installations. On the other hand, I also like screening my films in traditional theaters, like at Stadtkino now or Fondazione Prada, and at the Tate Modern in September this year. It allows the works to be seen in a cinematic context with a curated screening sequence. But I also value exhibition settings, where the space itself becomes part of the installation and experience. For Kunsthalle, the setup was designed as a backstage experience: upon entering, you walk through curtains from the non-velvet side. The speakers are exposed, and everything is brightly lit. When you finally enter, you’re on stage, facing the audience in seats. It mirrors the act of watching a movie and being watched while watching. La Gola is deeply focused on the eyes and emotions that are shown through them. The story unfolds in an almost theatrical way. For me, creating a show means engaging with the space instead of denying it. Converting it into a dark room makes it feel like a theater rather than an exhibition space. The audience’s movement is crucial; viewers should feel free to settle where they choose or to wander as they wish. It’s about the interaction with the space and elements within it, especially spaces with strong social connotations.

You mentioned the importance of eyes in La Gola. In the publication of the film, I noticed a page in the publication with a collage showing the characters and photos of your eyes. Were your eyes the inspiration for Gianni and Rossana’s?

When working with a CGI artist, I need to be as specific as possible. The more precise the reference, the easier it is for them to work. I took pictures of myself and edited them as collages, adding notes as references. However, they aren’t meant to represent my eyes in the final version. I’ve done this in other CGI projects as well.

What remains of a conversation when two people only exchange letters but aren’t actually talking to each other, sharing more of a stream of consciousness? We still sense their connection through the letters, which are full of kisses and longing. Is there empathy between the two?

They are lovers, yes. Gianni is a humorous character. For instance, he writes, “Sending kisses as sweet to you, Rossana. And another, no less sweet, to your mom.“ In Italian, this phrase doesn’t have a sexual connotation. But after describing a sweet cake, it feels a bit odd.

He has a Baroque way of speaking, almost stereotypical of melodrama, with two monologues forming a comical dialogue.

It’s a hetero-romantic relationship between them. How would you explain the comedic aspect and the highlighted gender roles in the work? Does it play with traditional ideas of what a woman and a man represent? I felt Gianni represents the body and more „rational“ side and Rossana is the one who is more spiritual and dreamy.

The division isn’t that clear-cut. They’re both discussing bodily experiences: Gianni speaks about the pleasure of eating, and Rossana speaks of bodily suffering due to illness. It’s a cliché that Gianni, as a man, discusses pleasure in almost pornographic terms while she, as a woman, cares for her mother. But they’re grounded and relatable. Gianni is almost spiritual in his twisted way, perversely speaking of food, while Rossana is more down to earth with her detailed explanations. If we stretch this idea, Gianni’s focus is speculative and abstract, whereas Rossana’s is very much grounded.

When discussing physicality and extremes, the characters in La Gola are actual puppets made of silicone, existing in the material world as well as on screen. Have you ever thought of exhibiting them, or is that out of the question?

For me, the puppets are like a painter’s brushes or pigments—tools. They stay in my archive and serve to aid in making the artwork, not as artworks themselves. If exhibited, they would become artifacts or documents. I keep everything—costumes, sets, and prosthetics—but I’m not interested in showing them.

Your projects involve large teams and collaboration. How do you choose your collaborators?

Camilla Romeo is the project manager and producer, and I have many collaborators who are also friends. Federico Chiari, the composer, has been my friend since high school. Diego Zuelli, who handles CGI and special effects, is another close friend. Lorenzo Cianchi and Giulia Gruescu, for what concerns material, puppetry, and scenography. Or Giulia Pecorari for the costume. Making films is not only a creative process but also a political one—a way to build a community.

Do you recall anything from your studies that influenced the way you work today?

I remember professors saying that people in art don’t often give so much time to a single video piece. But I thought, I don’t care; everyone is free to do whatever they want. I’m not making TV or ads that require undivided attention. This mindset led me to make my films that stand firm in the space, often using loops.

Lastly, what are you reading, and what was the last film you watched?

I rewatched Carrie by Brian De Palma because it was in cinemas for Halloween. I also just finished reading The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen.

For me, creating a show means engaging with the space instead of denying it.

For more information about the exhibition visit: www.kunsthallewien.at

UPCOMING:

Film screening and artist talk with Diego Marcon on 19.11.2024 at 8:00 pm at the Stadtkino im Künstlerhaus (Address: Akademiestraße 13, 1010 Vienna).

A special program of short films and videos by Diego Marcon followed by a conversation between the artist and Eva Sangiorgi, Director of Viennale. Diego Marcon’s work draws upon different cinematic vocabularies from diverse genres including musicals, melodrama, horror, and slapstick comedy. His uncanny, singular imagery employs various technical devices such as robotics, prosthetics, and CGI. Words, sounds, and gestures contribute to the troubling uncertainty or ambiguity that underpins Marcon’s work. Specially commissioned soundtracks or scripted dialogue are fundamental to his films, developed with careful attention to language and its mutability.

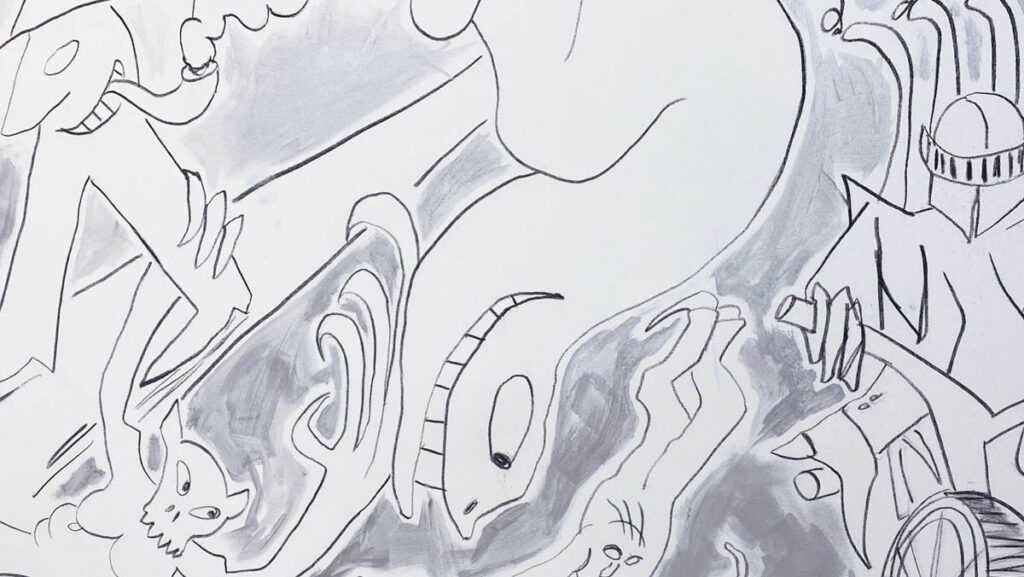

![Diego Marcon Untitled (Head falling 05), 2015 [Still] 16 mm film, fabric ink, permanent ink and scratches on 16 mm clear filmleader, color, silent 10 sec, looped Credit line: © Diego Marcon. Courtesy the Artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London](https://www.les-nouveaux-riches.com/wp-content/uploads/diego-marcon-video-still-04-890x676.jpg)

Film programme:

– Fritz, 2024 (4 minutes)

– Head falling 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 2015 (5 minutes)

– Ludwig, 2018 (4 minutes)

– Monelle, 2017 (16 minutes)

– The Parents’ Room, 2021 (10 minutes)

– Untitled (All Pigs Must Die), 2015 (1 minute)

– Dolle, 2023 (30 minutes)

Tickets are available at www.stadtkinowien.at and directly at the cinema – Akademiestraße 13, 1010 Vienna.

Diego Marcon – www.diegomarcon.net, www.instagram.com/die.marcon/

Diego Marcon (b. 1985, Busto Arsizio, Italy) has held solo exhibitions at Kunstverein in Hamburg (2024); Kunsthalle Basel; Centro Pecci, Prato; Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Milan (all 2023); Museo Madre, Naples (2021); Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore/LASALLE, Singapore (2019); and Triennale Milano, Milan (2018).

His work has also been presented within numerous group surveys including Nebula, organized by Fondazione In Between Art Film for the 60th Venice Biennale; the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève (both 2024); and the 59th Venice Biennale (2022). Marcon’s films have also been screened at Tate Modern, London (2024); Cannes Film Festival; the Viennale, Vienna (both 2021); and the International Film Festival Rotterdam (2018). Marcon lives and works in Milan.

La Gola was commissioned by Kunsthalle Wien, Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24, Kunstverein in Hamburg, Sadie Coles HQ, London and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York; with support from the Fonds d’art contemporain de la Ville de Genève (FMAC) and Fonds cantonal d’art contemporain de Genève (FCAC). The exhibition at Kunsthalle Wien is realized with the kind support of the Italian Cultural Institute in Vienna. The support is provided on the occasion of the Giornata del Contemporaneo. The accompanying publication is supported by the Directorate General for Contemporary Creativity within the Italian Ministry of Culture under the Italian Council program (2024).