After some time, each woman, dressed in white and with her long hair braided, is kneading a separate dough-snake of her own. Lastly, the three braid the dough into a big challah; their body gestures resemble dance while they move each piece in a different place.

„Challah“ is a new video art piece by artist Elisheva Revah, now presented as a part of „The Contours of Others,“ a group exhibition that was recently opened in Venice’s Jewish Museum as a part of the Venice Biennale (curated by Marcella Ansaldi, Jemma Elliott-Israelson, and Avi Ifergan). Revah, nowadays based in Paris, grew up in the mountains of the Jerusalem district, a child of two artists who raised her and her siblings close to nature and art. „My father is a multidisciplinary artist; he was a member of the Ein Hod artists‘ village, and my mother founded Klill Eco Village, so both are people who choose their own special path,“ says she. „When I was a child, they chose the path of repentance, a spiritual path.“

She is not the first in her family to be creative. Besides her parents, her grandfather from her mother’s side was a scientist („he was a scientist, but he was very creative,“ she adds), and the one from her father’s side was a bard. „A few months ago, when I was in residency in France, and I had an amazing studio,“ she tells me, „my father told me that when my grandfather arrived in Israel from Morocco and the family slept together on one big mattress, he made himself a studio. He put a small desk inside the closet, and he would simply go inside, close the door, and write. So, we have a legacy, I think, of people who create.“

Her mother is a sculptress who chose to become a therapist and to focus on domestic life, cooking on fire, and making cheese from their goats. Elisheva grew up between her father’s studio and the family’s animals, practicing multipole techniques with her father as a daily routine. „I saw my father playing instruments, drawing, and making sculptures, and that’s how I slowly learned techniques. He would take a piece of paper and put it underneath a tree, then ask me to draw the shade that was created from the sun’s reflection. That was our quality time together. I have always been drawing and dancing, so for me, creation was a natural path.“.

When she was 12, her mother suggested she join drawing classes, yet her father denied it, fearing that the institutional path would oppress her creativity. „They had a very anti-institutional view, which probably influenced my decision not to study art professionally,“ she explains. She decided to leave music and composition, which she studied along with ballet, and to become a professional dancer. „I thought the painting was a place where I shouldn’t erupt. I took ballet very seriously, and it was only at the age of 16 that I understood that I wanted to do choreography. I realized that choreography is positioning compositions in space with the body. I was very passionate about it. Then, at the age of 18, I was injured and couldn’t dance. There were a few years when I just gave up on dance and put art and creation on hold. I felt that I needed to find myself.“.

Was there a sense of anger in your body?

Betrayal of the body. It was kind of a trauma. I felt that I had lost control of what I wanted in the way I saw my life and my body. Years later, one of the first things that happened when I started creating was that I danced. To this day, when I start working in the studio, this will usually be the first thing I do.

As if the movement of the body will bring the movement of the material.

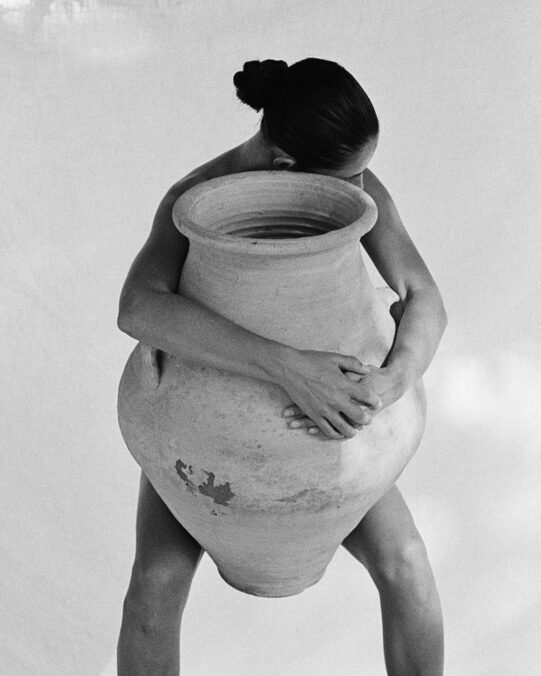

Yes. It can be either to connect to myself, to become present, or to get into some state. It’s a mirror. When I started painting daily, I would undress and play with the compositions and movements of my body in front of my camera. Then I would take screenshots, and that was my tool, meaning that I was my model.

An experience of taking control again of your own body?

Exactly. And to get back into my own body.

Spiritual nourishment. She spent the years after her injury in multiple fields such as therapy, horse riding, and traveling, then art found its way again into her current occupation. „I think I needed to find that channel from which I could be completely free to create,“ she says. Yet regarding other fields in which she learned professionally, Revah decided to become a professional artist in a self-thought-out way. „Choosing not to go to study art has a price. I’m walking into a world of which I know its essence—not the laws nor the people. It’s all very intuitive, but that’s also the advantage. This is my freedom.“.

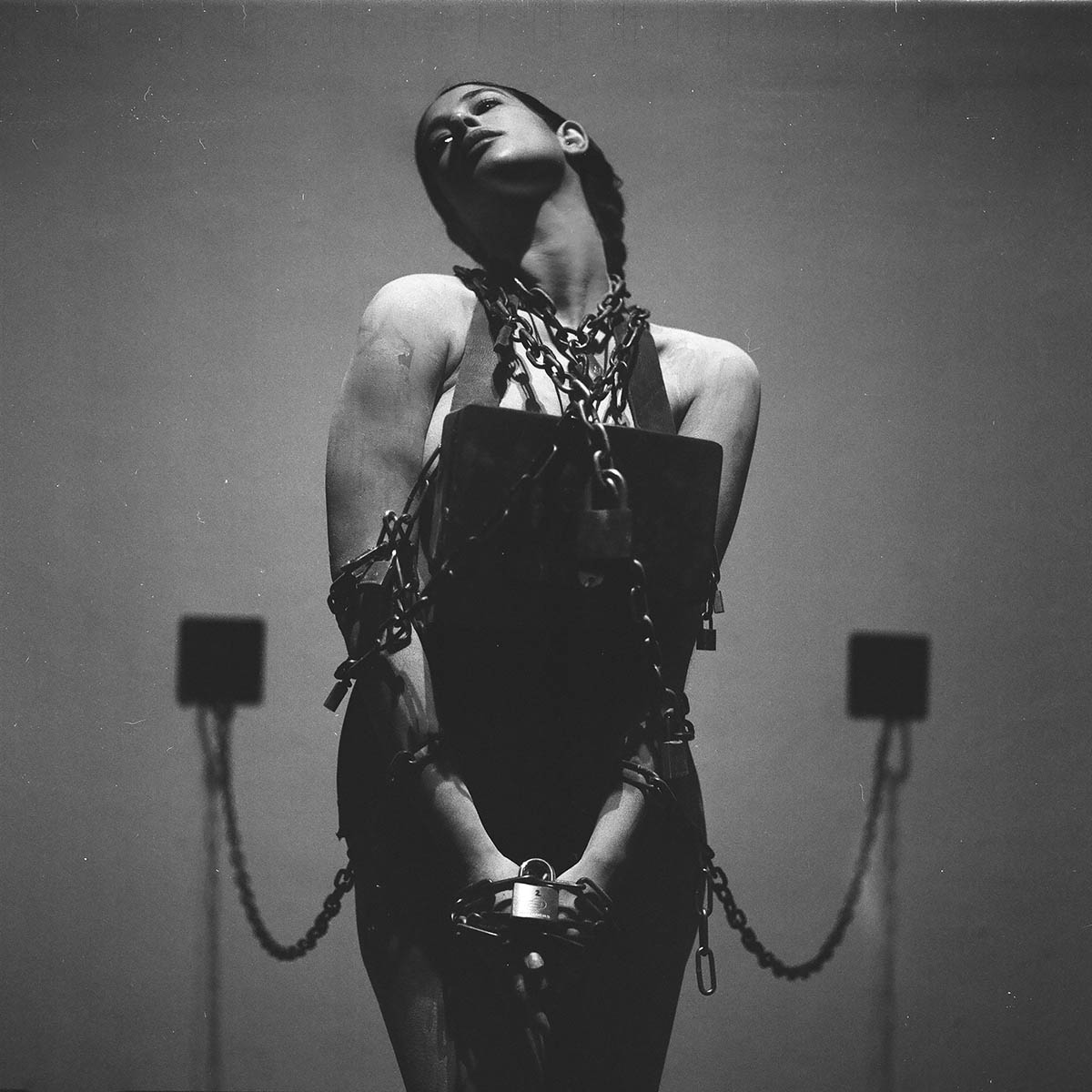

In the last couple of years, she has exhibited a solo exhibition (When the Moonrise, 2021) and several performance works, such as „Woman“ (2022), „Chains“ (2023), and „Rebirth“ (2023).

Elishave: Each of my performances is different, yet I think there is one thing that connects them all, which is a feeling of a ritual or a ceremony. Judaism was practiced at home as I grew up, along with a connection to nature, so there were a lot of rituals around me. Also, while I was looking for my way, I approached Tibetan Buddhism and Sufism. The ritual is a moment to go through some kind of process, an experience with an intention. My performance pieces are a kind of ritual (not religious), in which I also invite the audience to take part.

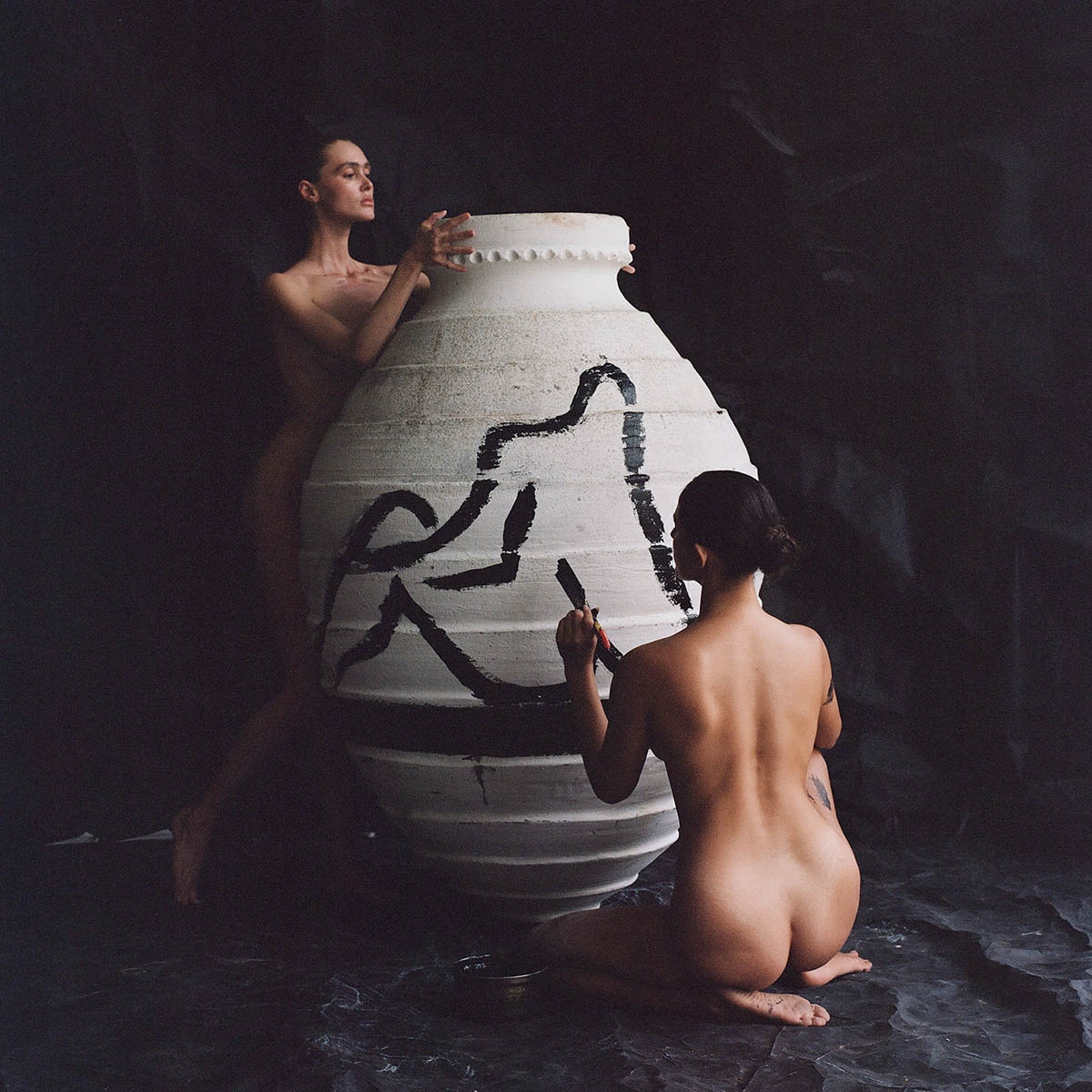

Revah’s work, which was commissioned specifically for the exhibition upon the request of curator Jemma Elliott-Israelson, is, in a way, a transformation of her performance work into video art. On the first one, a group of women is making a grand challah, the Jewish bread (from 100 kilos of dough), while on the second one, another group is braiding a pregnant woman’s long and heavy hair. One can identify Revah’s interest in both feminine rituals and Jewish ones by his strong connection to the body and its movement.

Can you explain a bit about the idea behind „Challah“?

Shabbat is something that gives every Jew a sense of belonging wherever he is in the world, regardless of religious practice. In Judaism, the woman makes challah every Friday; this is one of the mitzvot that is saved solely for women. Then she does the Challah offering—she takes a piece out of the dough, puts it aside, and blesses her loved ones, her relatives, or even a sick acquaintance.

Even though the challah offering has become a popular costume among women before their wedding, Elisheva explains that this blessing happens every time one makes bread. „This means that every dough you eat has been blessed,“ she says. „This means that bread, the most basic food, should undergo some kind of blessing. I found it interesting that a woman not only nourishes her family members physically but also spiritually. This work deals with nourishment in a physical, spiritual, and emotional sense. I took 100 kilos of dough to increase the scale, and three women processed the dough, kneaded it, and then made challah. It was a physical work, so this piece is also a tribute to the feminine toil of our ancient mothers, who somewhat disappeared from our world. But it still exists; we still make food, and we still do laundry. It just isn’t considered important in our culture.“

Some may tackle your work and ask, What is femininity? What is gender?

This discourse does not concern me. I don’t cook much, but I have the power of nourishment. I have a womb. And even if I don’t have children, I have this ability that exists within me. It’s not about making bread. I don’t think every woman should make bread—not. Bread is some kind of basic food; it is only a symbol here for nourishment. The second work is more about women feeding each other. Here there is a pregnant woman, who, of course, is currently feeding a baby. She has very long hair, and the women are busy nurturing her. The women are braiding a long string made of hair, which reminds me of the umbilical cord. There is a Midrash Hagada (commentary on the writings of the Torah and the laws of Halacha) that says that when God brought Eve to Adam, he braided her hair. My father explained to me that God wanted to symbolize Eve’s complexity and mystery to Adam. He used a braid as a symbol since it is impossible to trace which part is inside the braid. This inspired me a lot.

How, in your mind, does your work relate to the Biennale’s theme, „Foreigners Everywhere“?

As Jews, we have been immigrants for generations. I am the daughter of immigrants; my grandparents were immigrants, and I am now an immigrant myself. I think that challah reminds me of home. Food is the most basic thing that connects us to who we are. For example, immigrants can be completely integrated, but if you go into their house, you will see the traditional cuisine from their homeland. Since October 7th, I have understood how the fact that I am a Jewish woman is an issue. And I say, OK, if so, then so be it. I will embrace it even more. I draw a lot of strength from the sources of my roots and my tradition, not necessarily in a religious manner.

On the opening night of the exhibition, which was held during the opening of the Biennale, Elisheva held a performance in which she made a giant challah with four international performers who chanted an a-cappella that was composed especially for the occasion by composer Shlomi Frige. „The reason I wanted to have music is, once again, to return to women’s rituals. In ancient cultures, some rituals were accompanied by sing-alongs. A few days before the opening, I had a sudden worry that I was going to perform at the Biennale, and all I would be doing was making a challah. Then suddenly I looked at it from a broader perspective, and I thought about the period we are in. And I realized that this is the answer that I have. In a very masculine world of war where everyone is loud and has an opinion, there is something very feminine in silence. To continue my truth, to give what I can, to nourish whom I can. This is my answer.

Elisheva Revah, participating in the group exhibition „The contours of otherness“ at Venice Jewish Museum, with the work Challah, 2024. Curated by: Marcella Ansaldi, Jemma Elliott-Israelson, and Avi Ifergan.

Address and contact:

Venice Jewish Museum

Cannaregio 2902\b., Venice

www.ghettovenezia.com

Elisheva Revah – www.instagram.com/elish

Gal Houbara Bergman – www.gal-hb.com, www.instagram.com/gal_hb/